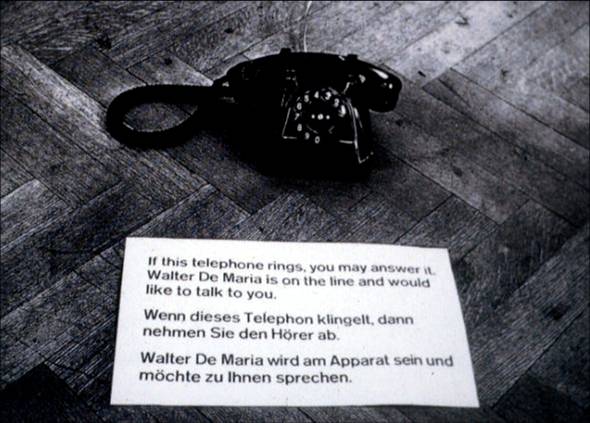

Walter de Maria, Art By Telephone, 1969, installed in “When Attitudes Become Form,” Kunsthalle Bern

For the 1969 conceptual group show “When Attitudes Become Form,” curated by Harald Szeemann at the Kunsthalle Bern, Walter De Maria submitted Art By Telephone.

A black phone sat on the gallery floor next to a little sign in English and German: “If this telephone rings you may answer it. Walter De Maria is on the line and would like to talk to you.”

In his wonderful book, The Lightning Field, Kenneth Baker quotes from De Maria’s proposal for the piece that the artist will “telephone into the exhibition and over the period of the month use $200 worth of telephone time in conversing with whichever visitor’s fate may have been placed near the telephone, about any subject at all.”

Besides this invocation of fate, which, more in a minute, I’d completely forgotten the artistic implications of international long distance charges. Phone calls used to be really expensive. I can’t find the rates for Switzerland, but a November 1969 article in the NYT mentions a NY-to-London rate of $2.40/minute. So De Maria’s piece would have been maxed out in less than an hour and a half.

If he’d called. Which, according to Germano Celant, who was involved in putting Szeemann’s show together, and who restaged the now-landmark exhibition last year in Venice for the Prada Foundation, and who discussed the show(s) in February at the Reel Artists Film Festival in Toronto, he never did. In video of Celant’s talk, which was just posted by Canadian Art, Celant answers a long statement/question about restaging as autobiography:

Or Walter De Maria, that gave us the phone, and he said, “I never called.” You know, the piece is the phone and it says, “When the phone rings, on the other side will be Walter De Maria speaking to you.” But he never called in Bern. [audience laughter]

So De Maria pocketed the money? So smooth, so hilarious. I’m sure had they known, the Swiss would have protested that, too. Celant goes on:

So I said, “Walter, what we can do?”

“Oh, no no, this time I will call.”

[audience laughter]

And he did. And he spoke with Miuccia.

Oof.

image: getty for prada, via let them talk, which lol

Here’s that convo, by the way, from the May 29 opening part of the show, placed by fate and publicists. Now the driveway moment:

You know, there are so many personal things, you know, then he was supposed to call me, and, unfortunately he died.

And so then we have to take the piece off, because naturally, after he passed away, the piece was not available–was not possible anymore, you need–when the rings start, on the other side is Walter De Maria, but Walter is dead. So we have to took a picture, and we have to replace–so there’s this kind of life element in this kind of show, that I like very much, and that’s biography.

Damn. This. This is why I’m a fan of unscrubbed transcripts. It just feels more.

Also, I’m really not clear why they had to remove it once the artist died. Wouldn’t his not calling at all be a more historically accurate recreation of the installation in Bern? The Venice show opened June 1st, and De Maria passed away on July 25th. Roberta Smith’s obituary said he’d had a stroke in May, but was undergoing treatment. Did he call anyone else? Was he still able to talk? If not, was it still somehow less problematic to show the piece when he was alive, but incapacitated?

Because, though I readily acknowledge Celant knows the artist and his intentions for the piece far better than I do, but I’d totally show that phone. The idea of leaving the phone out after De Maria was gone is not nearly as sad as the idea that the only person he spoke to was Miuccia Prada. Besides, what if he called?

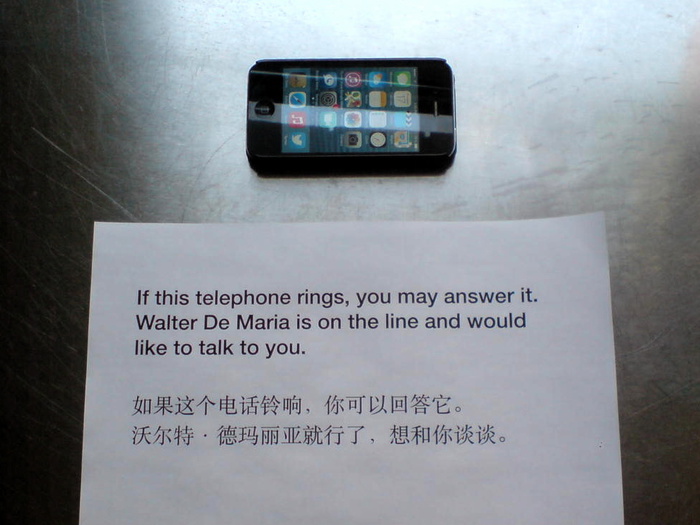

update: Untitled (Study for Art By Telephone, After Walter De Maria), 2014