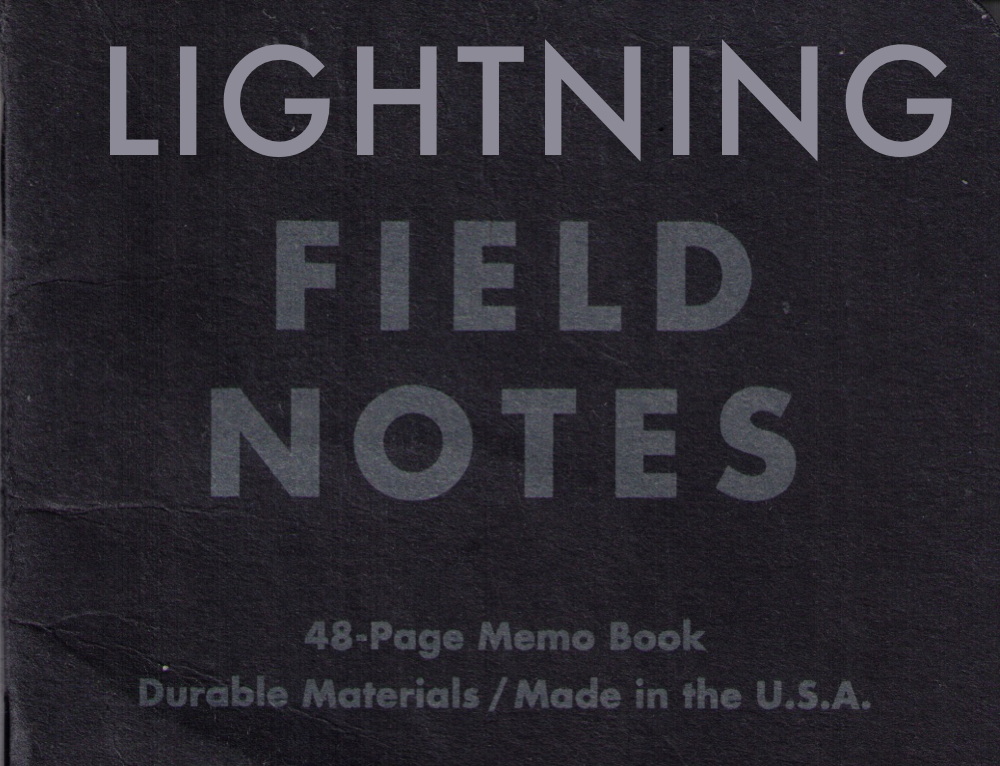

John Cliett’s photo of Walter de Maria’s The Lightning Field, 1977, on the cover of Artforum (Apr. 1980)

From the beginning, access to The Lightning Field has been tightly monitored by the administrative machine surrounding the project. Visitors to the site are required to spend the night and are not allowed to take photographs during their stay. Indeed the entire project is predicated on the viewer’s personal physical experience of the work in its location. Yet, at the same time, the artist and his patrons have also sought to stake out a particular presence in the wider discourse of contemporary art for The Lightning Field, a goal they have accomplished in part through a carefully orchestrated approach to photographic documentation.

[John] Cliett worked from the beginning with De Maria on formulating the scheme for photographing The Lightning Field; many of the most often-reproduced images of the Field, including those which famously introduced it to the art world in the pages of the April 1980 issue of Artforum magazine, come from his two summer sessions. Indeed, that so many viewers have come to know The Lightning Field through these images–a fraction of the total he took, strategically promulgated over the years by the artist and Dia–emphasizes their essential role in the artist’s plan for shaping the image and promoting the “idea” of the work.

Well beyond the artist’s own writing, Jeffrey Kastner’s interview with The Lightning Field photographer John Cliett has been central to my understanding of the work since 2001.

Cliett told of taking the extraordinary, iconic, and extremely difficult pictures of The Lightning Field, but also of how images are antithetical to de Maria’s concept for the work. This contradiction between the artwork and the art system surrounding it generated tension similar to other Land Art. During the 1970s and 80s when Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty was considered “lost” or invisible under the Great Salt Lake, the artist’s film became the focus of critical attention.

De Maria felt that even this iconic imagery, which Cliett later jokingly compared to “a Pink Floyd album cover,” could only ever fail to communicate the experience of the work. “Walter’s work is designed to create an environment where a viewer can have a highly personal relationship with a work of art that is completely unique to each individual,” Cliett said.

But the images had another purpose, controlling the discussion of the work, as I was reminded when I re-read Kastner’s interview this summer:

With respect to the copyright, if you control the picture of a work of art, you will control everything that’s said about it, because nobody will publish an article without pictures. So you get the right to pick, and that’s a very powerful thing.

Yes, well.

After many discussions, dreams, and failed attempts over 22 years, we managed to get a trip to The Lightning Field together for this summer. We built the rest of our cross-country road trip around it and got home a couple of weeks ago. A visit takes basically 21 hours, starting at 2pm, no stragglers. Dia’s folks on the ground drive you to and from the remote site. There is room for six people in the cabin; in addition to our family of four, there was a young couple from Brooklyn.

I’m not sure when I decided to livetweet our visit to The Lightning Field, maybe after I started seeing people I knew from Twitter in the registry. Or when I read one excited, tweet-sized comment left by a dealer about soaking in the sublime, which seemed like a lot to feel before you even get there. And so as I was about to learn the difference between an image and an artwork, I started thinking about real and virtual, individual and network, living and publishing, an account and an experience, a livetweet and IRL.

Without wanting to blow my actual encounter with The Lightning Field, I was interested to isolate what happens when you approach an experience with a livetweeting mindset: do livetweeters dream of 140-character sheep? Since there was cameraphones, and no hope of connectivity anyway, I decided to write my tweets down. My black Field Notes book looks very iPhone-ish, and I was quickly aware of being glued to it like any other screen, so I did not write every tweet in real time; I’d put some in my mental drafts folder and batch them.

There’s still a lot that didn’t make it in. Stuff I left out. But from there, also what de Maria left out. After several ventures into and around the Field, the artist’s almost total silence on the land itself is stunning. “The land is not the setting for the work but part of the work,” wrote de Maria, in bold, at the beginning of his Artforum essay. He wrote that the site was “searched by truck over a five-year period,” and that’s about it. The entire rest of his statement is about the hyper-precise calculations, surveying, and technical challenges of manufacturing and installing the poles. There are two pages of credits for the companies and construction workers involved.

Like Cliett’s photos, de Maria’s industrial fetish text was intended to manage the discourse around the work. No one could dismiss it as nonsensical, non-serious or unintentional. And it’s not some basement project, either; this is not your grandpappy’s mile of fence. Yet the only way to get around The Lightning Field is on foot, and the landscape makes you literally watch every step. And then there were the coyotes howling at sunrise, hoo boy, that was freaky.

I ended the livetweeting right before our ride came, but one of the most interesting parts for me was the drive back to town, and the conversation with Kim, the longtime Dia staffer who runs the guest program on the ground. I decided not to tweet that, though, just as I didn’t really mention our cabinmates too much. Besides basic respect for their privacy, I figure that’s also truer to the work: tweets aren’t reporting, but a reflection of a single, individual experience.

Once I had this notebook of tweets, I had to figure out what to do with it. I scanned them and figured I’d play them back, tweet them in real time. That idea quickly ran afoul of my schedule. I guess I could have set a script to automatically post them at the prescribed times, but instead I tweeted each by hand, beginning yesterday at around 2 o’clock New Mexico time. I didn’t anticipate the friction of overlaying this recap of The Lightning Field with my back-to-normal life. Where visiting The Lightning Field was an intensely physical experience, livetweeting The Lightning Field became all about time. I could not anticipate the next tweet accurately; I was always way too early. I got in trouble for tweeting at the dinner table. I realized only after I started that twitter-as-usual would kind of blow the whole thing, so I stopped retweeting and responding to people until it was done. [Sorry!]

I may work the tweets up into an edition, a facsimile notebook or something. Dan Perjovschi made a little sketchbook facsimile for Kunsthalle Basel a few years ago that I like, and Field Notes are the perfect on-brand readymade. Or maybe I’ll do some other project, involving barnwood, Hudson’s Bay blankets and yoga mats. I don’t know yet, but something’s sure to come of it.