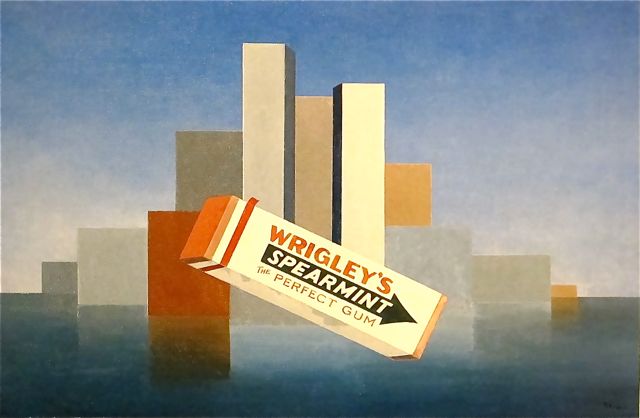

Wrigley’s, 1937, Charles Green Shaw, Art Institute of Chicago, image: poulwebb

The banner on J.S. Marcus’s WSJ story about American painting in the 1930s is Charles Green Shaw’s Wrigley’s, which is in the Art Institute of Chicago collection. Also, it is awesome.

With its unafraid abstraction mixed with proto-Pop, it reminds me of Gerald Murphy’s paintings from the 1920s. Shaw and Murphy both enjoyed privileged, Manhattan-based, continental lifestyles that involved painting, and according to Adam Weinberg’s 1997 exhibition brochure, they were friends in Europe.

But his AAA history doesn’t mention Murphy at all. Shaw didn’t get into abstraction until he came back to New York, well after Murphy stopped painting. And Shaw doesn’t seem to have been very involved in the artist community of New York in the 30s, despite having a couple of gallery shows, and being on some committees at The Modern. He was more a writer.

Which makes it tricky to gauge the quality/influence/familiarity of his work. It’s nice, some of it, like Wrigley’s, even looks great, but it doesn’t seem to have been important or impactful. The historical upside is limited, is how it feels. This, even though he was apparently friends with Ad Reinhardt. I guess it’s complicated?

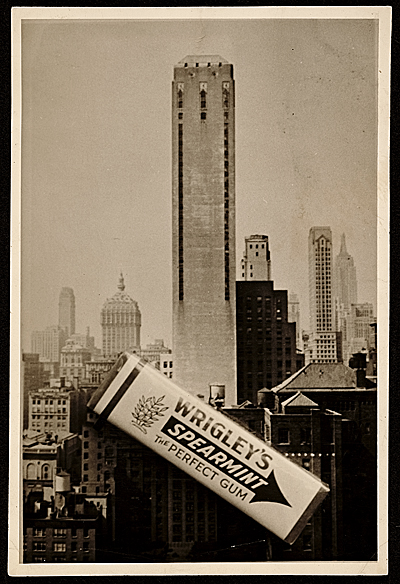

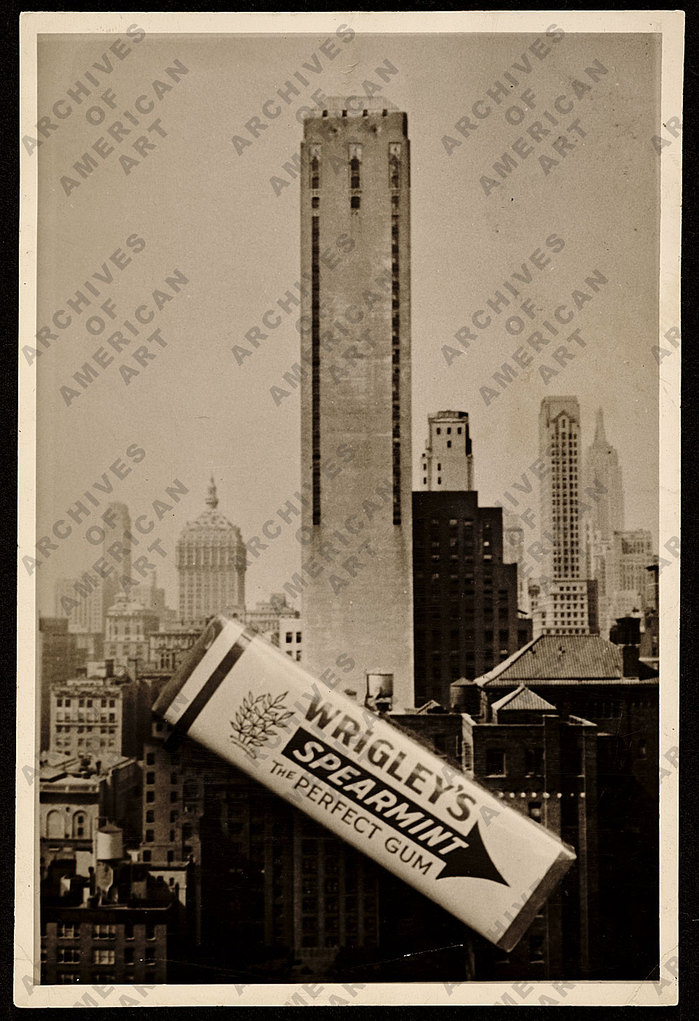

Still, it’s good to see this photo of a pack of gum sitting on a postcard, which looks like source material for the painting. It’s among the digitized collection of Shaw’s papers at the Archives of American Art. As the larger version of the image so ably informs us:

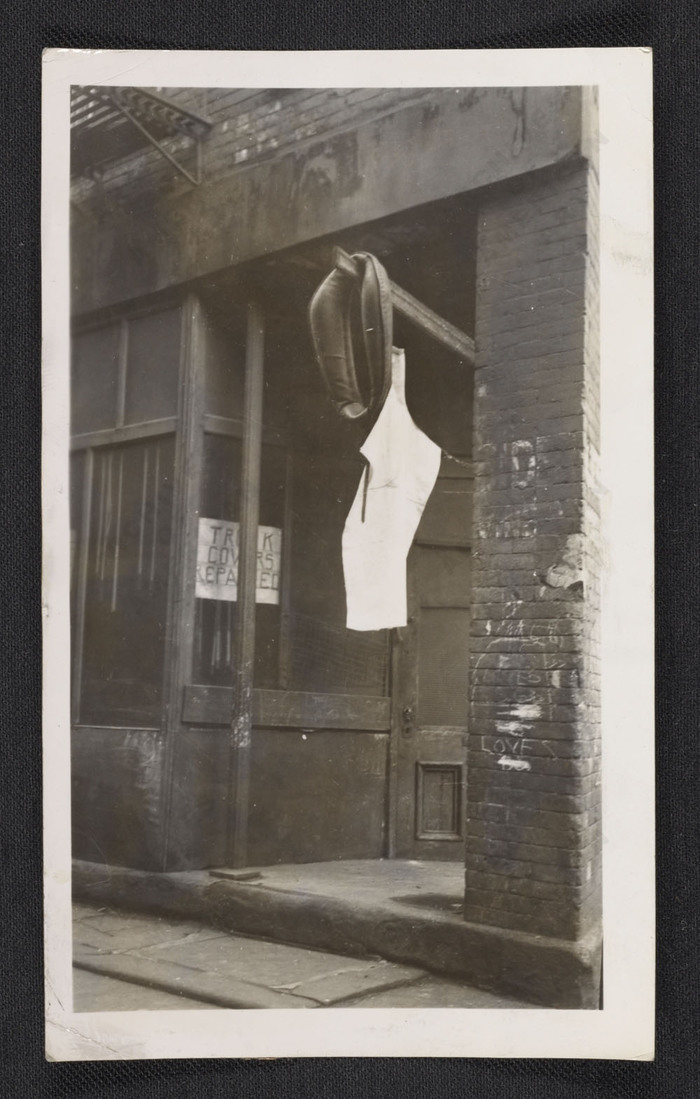

Maybe it’s hard to put an emphasis on Shaw’s painting because he had so much else going on. He wrote for the New Yorker, did slim books of verse, cranked out some children’s books, took photographs.

Charles Green Shaw, photo of NYC harness store, c.1940s?, collection aaa.si.edu

We might call Shaw an artist fluent in multiple mediums today, but his is the kind of peripatetic practice that we’re conditioned to look askance at when we see it in the past. Or maybe it feels like he did not take much of anything seriously, except for mixing drinks. Maybe it’s because he was rich and a “bachelor” in a time and art world where that didn’t help?

I don’t really know, but I like the work.

Oh here we go. In 2007 Roberta Smith also called him peripatetic and wondered, more clearly than I, about his legacy. His group of well-heeled colleagues, the American Abstract Artists, who were abstract when abstraction was un-American, “were often called — and not always benignly — the Park Avenue Cubists.”

When he died in 1974, Shaw left his art to a surprised friend, the collector Charles H. Carpenter, who became its posthumous shepherd. A bunch of paintings went to the Whitney, and the Art Institute bought Wrigley’s. And apparently, he’s been an overlooked American minor master ever since.

Charles Green Shaw papers [aaa.si.edu]

Charles G. Shaw’s artist page at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery [michaelrosenfeldart]

[nyt]

Skip to content

the making of, by greg allen