Late last October I saw an exhibition of George W. Bush’s paintings of veterans at the Reach, the new Kennedy Center annex designed by Stephen Holl. With all due respect to Verrocchio, it was the most significant painting exhibition in town last fall.

The show was the first in the Reach’s art space. It was installed in a single, large room on short, black, temporary walls. It was organized by the Bush Library or whatever and sponsored by Boeing. It required timed entry tickets, though the weekday I went, I was alone until an older couple showed up. The voice of Bush telling an anecdote about meeting this or that depicted veteran would break through the silence from their shared Acoustiguide.

This turned out to be one of the stated purposes of the exhibition, to “Learn the stories of each of the warriors featured in the exhibition; [to] Glean an additional appreciation for the service and sacrifice of those who serve in the United States military; [and to] Understand the impacts of the wounds of war–both visible and invisible.”

I went to see Bush’s paintings in person, to see how he makes them, and to see if that helps explain why he makes them, and what they do in public, when the wars he started are still going on, and the consequences continue to reverberate throughout the world. In a town utterly bereft of accountability, this show is the only consequence Bush has to deal with from his wars.

The immediately obvious difference seeing Bush’s paintings in person vs online is their facture. They are not just pictures, but painted objects. Some have flat, smooth surfaces; some have thick, impasto landscapes; some have both. None of the 66 paintings have any dates listed, so it is impossible to map out a narrative of technical improvement. Instead, I am left to conclude that each painting is exactly how Bush wanted it to be; after all, he is The Decider.

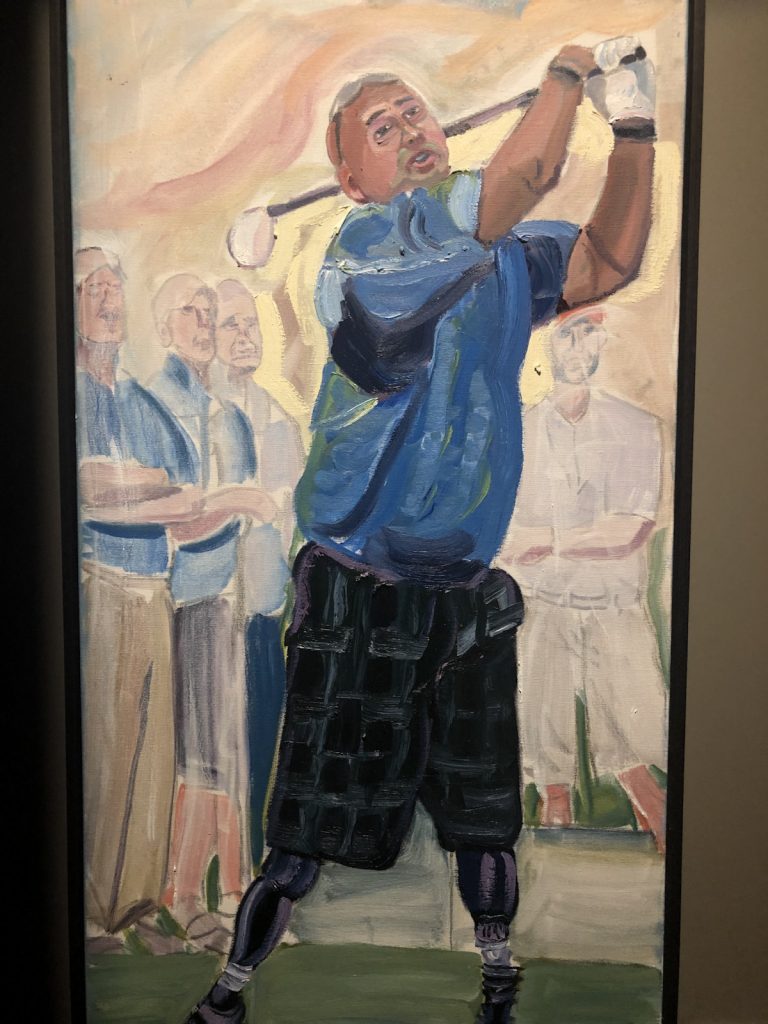

He talks of meeting the people he painted, but like his earlier series of world leader portraits, Bush painted these from photos. Sometimes the sketched in structure of the painting is visible, like in the ghostly viewers of a round of golf, or in the outline of a collar and chin.

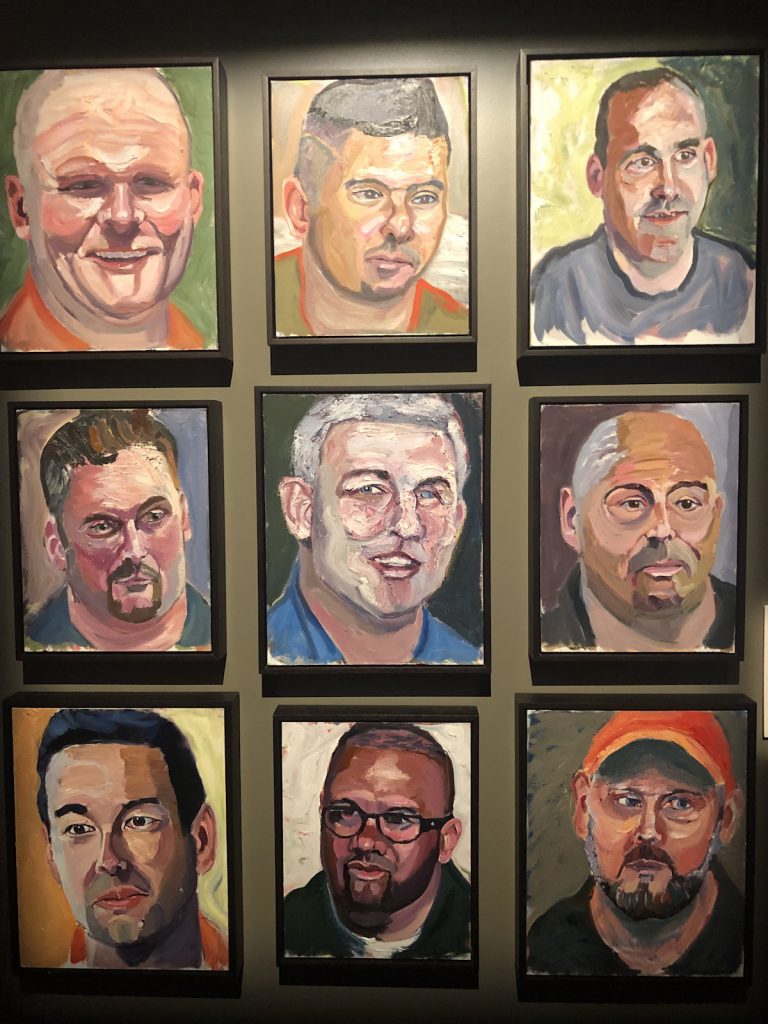

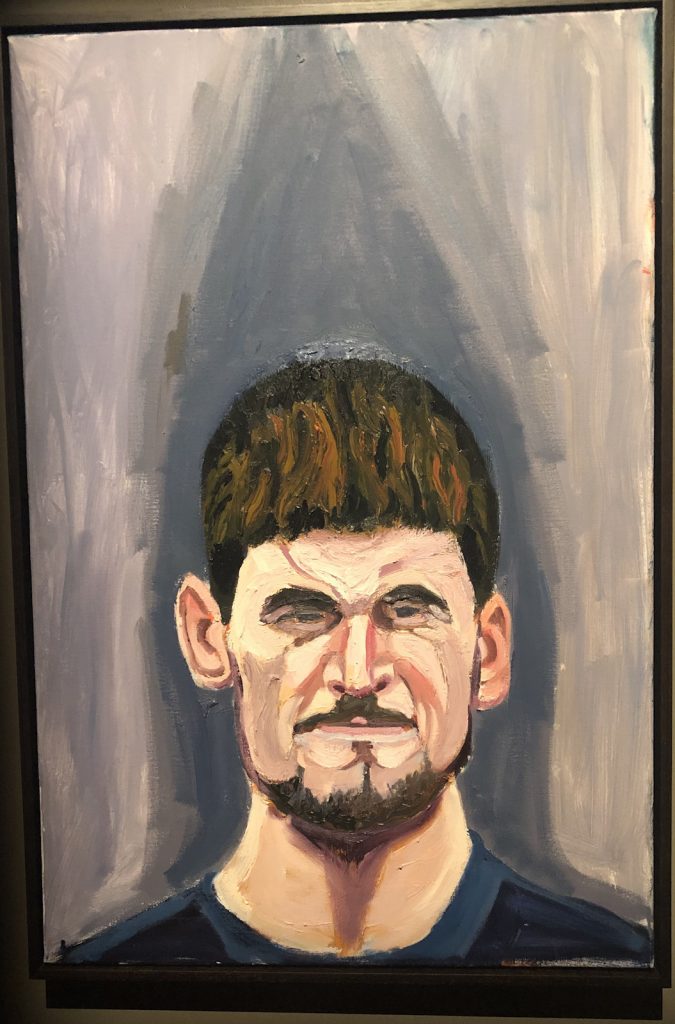

Except for that golfing one, almost all the paintings depict a single figure or head against a featureless background. These are typically painted quickly, with a large brush.

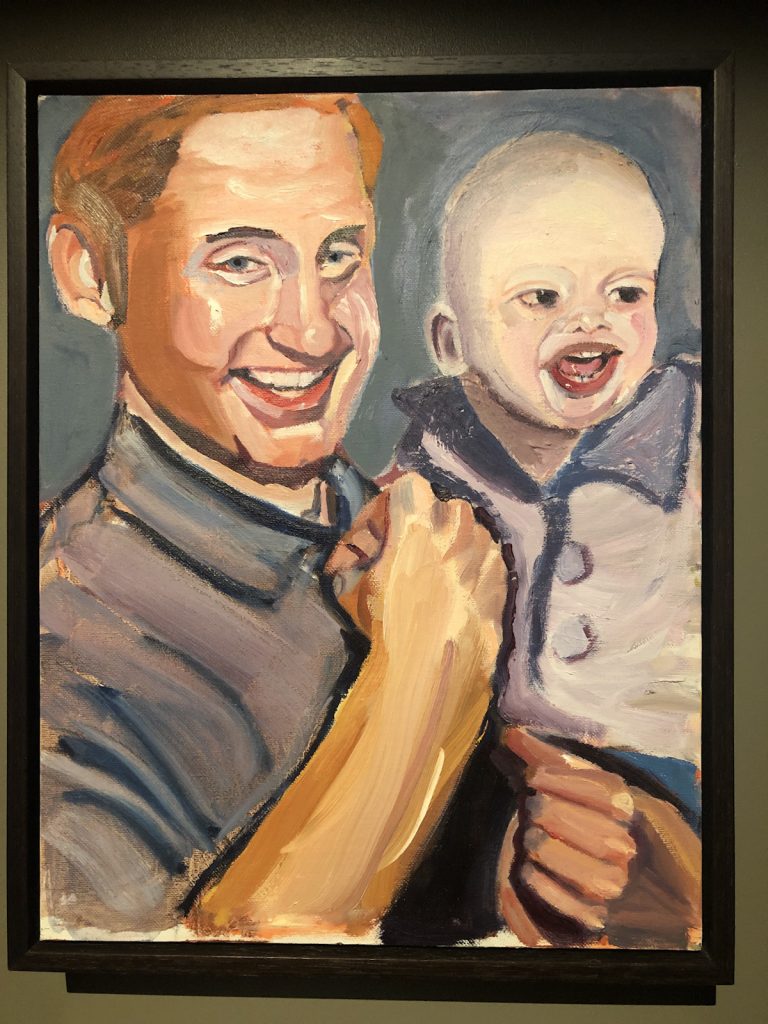

Actually, it’s not just the background. Everything about each painting feels like it was painted quickly, without hesitation or care for finer detail, such as space, or form. There are a few times when it looks like he took some time to get it right, like on the face of a baby, and it does not turn out great. So most things are hinted at, sketched out, filled in.

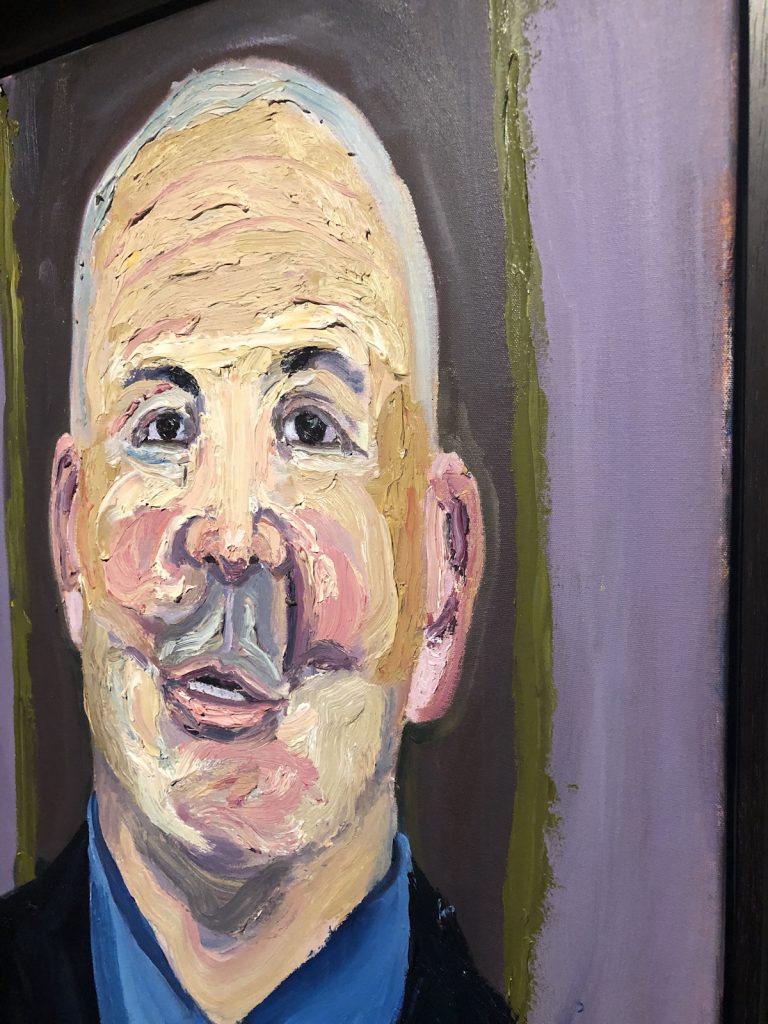

There are lots of spots around the edges of the canvas, and the edges between figure and ground where the paint does not cover. I am avoiding saying they are unfinished, or incomplete, but I came to the point where I couldn’t decide if it was The Decider or The DGAFer. There’s the black around the dad’s arm and hand, above, and the layered interaction between shirt, flesh, and line. but almost no sign of reworking. Except for this guy’s head once being too tall, there are no obvious corrections; he just painted and got them done.

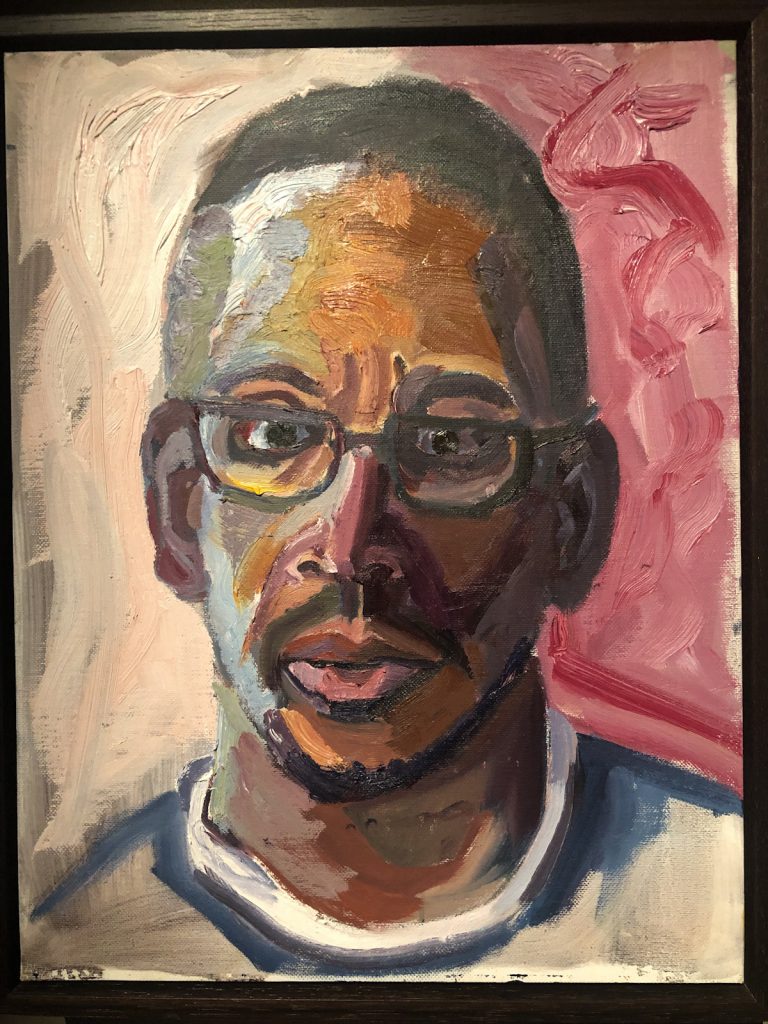

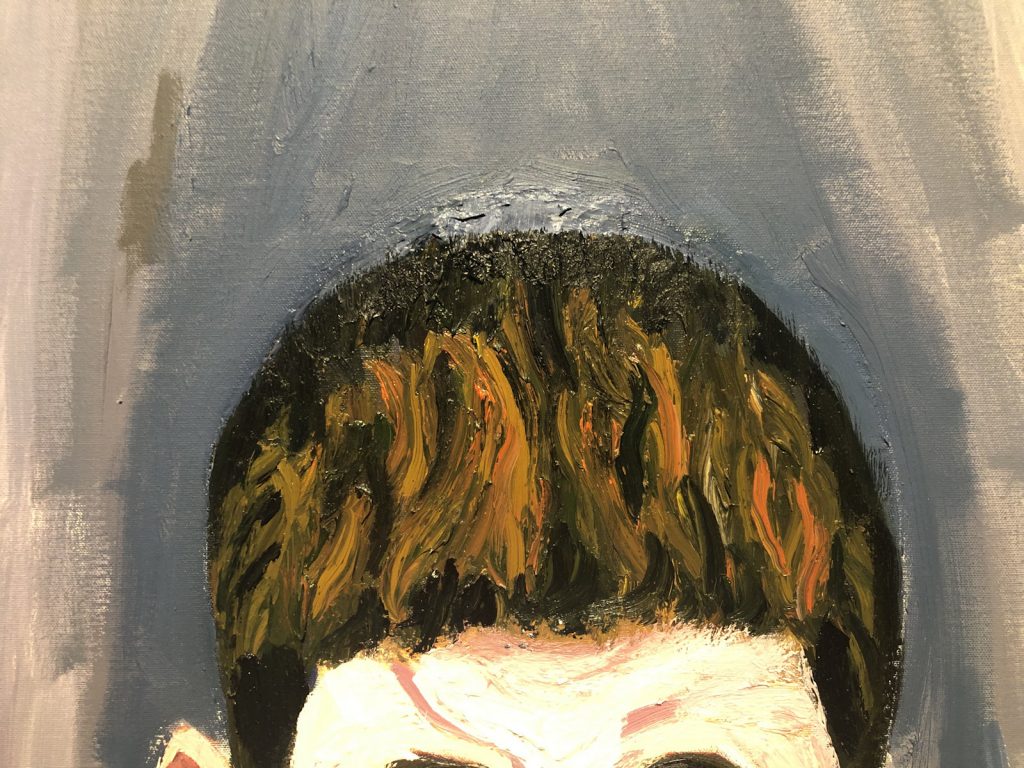

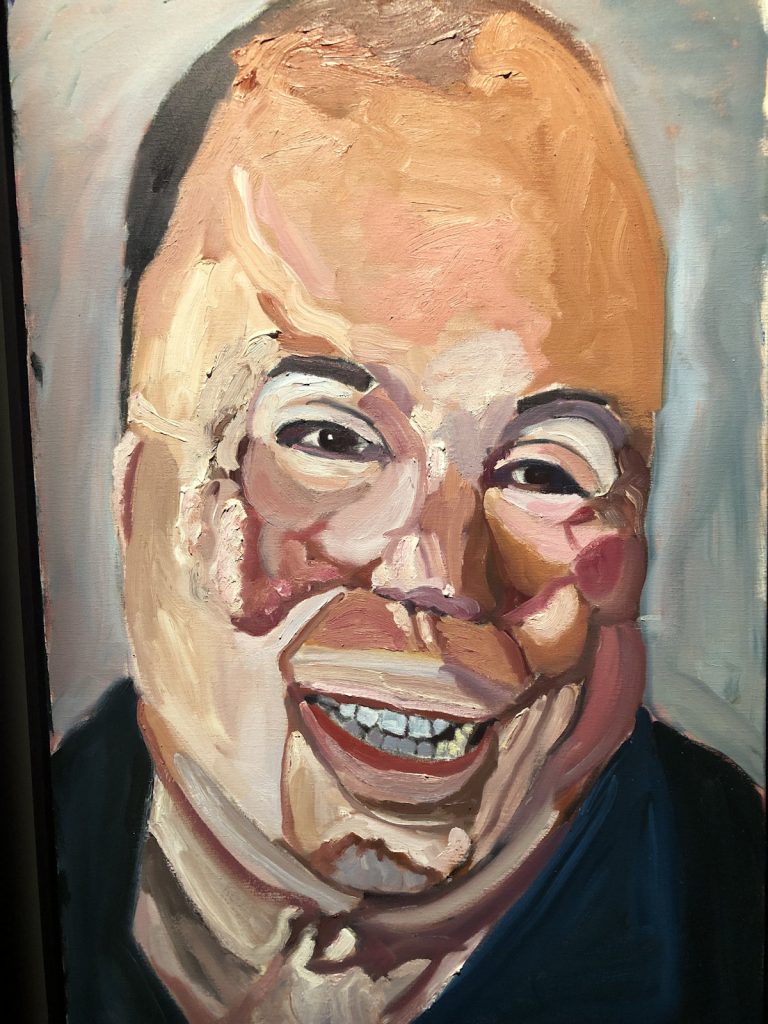

The colors are one of the most distinctive features. The highlights below, mixed on the brush, are their own thing.

More common are the many unblended zones of color on a face, or in a popping background.

When I walked through the show I could not help thinking of Alice Neel. When I have looked again at this skin, I have thought of Lucian Freud, or Jenny Saville. But I do not think art references are what the painter was thinking about. I think he was taught the basics of painting what he sees, and of not overthinking it. Repeat it often enough, and sometimes the resulting painting will be aesthetically appealing, even compelling. But the inclusion of so many paintings where that is not the case makes me think these accidents are not the point, if they register with the painter at all.

The point of these paintings is that Bush met these people–or rather, they met him. And then he painted them. In one overheard recording, Bush praised the endurance of the veteran who played a round of golf with him in Texas summer heat. In an era of commodified selfies and photo opps, paintings carry more cultural weight than photographs. And it somehow matters that the man who sent them into a war of choice spends a whole hour, or two, or more, painting their portrait. Just don’t think about it too hard, though, because Bush did not.

Post Script: Of course, the reason I went to see these paintings is because I still have a mind to continue to make paintings in Bush’s style. It had been difficult getting #ChinesePaintMill painters to capture the essence of Bush’s technique. It’s been almost four months, and it feels even harder to explain now. Also, I wonder if I should even try. Because after seeing this show, it is not clear that the world would be better off with more paintings like this in it.

Previously, related: Our Guernica, After Our Picasso

Our Guernica Cycle: EB-5, 05.06.2017