I had to go into Manhattan for a meeting, and so I slipped into a show I’d been aching to see: “(Nothing But) Flowers” is a sprawling delight of a group show filling both Karma galleries for the summer. It is a rich and fascinating respite, and a quiet, disarming way to approach what painters do with the simplest of subjects. Plus there was that Manet Moment the other day.

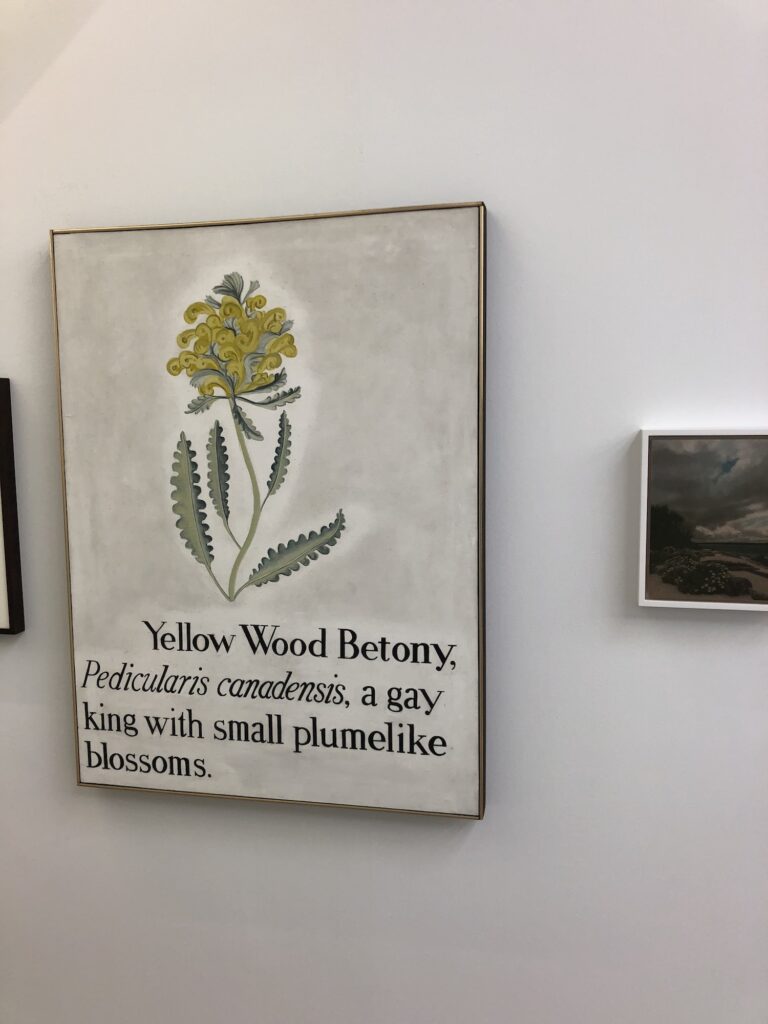

Anyway, one of the things I most wanted to see in person was this 1962 painting, Betony, from Vern Blosum. When I went up to the Berkshires almost ten years ago to meet the artist who’d painted under the name Vern Blosum, I was obviously interested to see his paintings in real life, but I was also nervous, concerned that this pseudonymous project had been a joke, a hoax, which he would disown, relegating his works to orphaned oddball status.

Turns out there was no chance of that.

He had one of the parking meters he’d wrested from the street to paint in his studio propped near the front porch. His brawny AbEx paintings and his Blosum paintings hung side by side throughout the house, along with different, later works, and there was a small painting of a flower, with its scientific name and a brief text caption, hanging in the kitchen, at the very center of his house.

I thought it was even more interesting than his parking meters, or the other street objects he painted, and more akin to the farther off paintings of John Baldessari than to the proto-Pop movement he was initially a part of.

But Conceptualism was not his concept. “Blossom, get it?” He said about the painting. He had painted other people as parking meters, but these flower paintings, he was saying, were not just the project’s beginning, but its self-portraits.

I don’t think I’ve seen that original (sic) flower portrait since. The five flower paintings Blosum showed at Essex Street in 2013 felt bigger to me, though they’re the same size as this one.

As I’ve not engaged Blosum’s re-emergence over the years, I’ve often not written about the source of these flowers, both their claimed autobiographic aspect, and their content; I’ve waited for someone else to point it out. No one ever has. But then this Karma painting turned up, with a twist, and I couldn’t stay quiet.

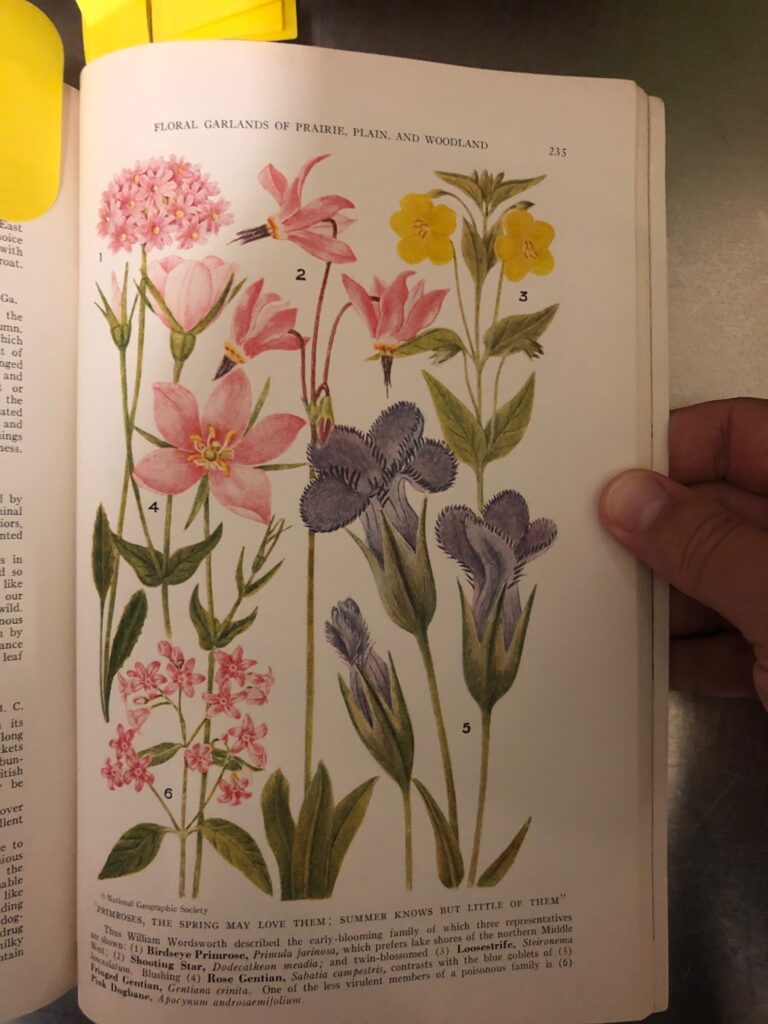

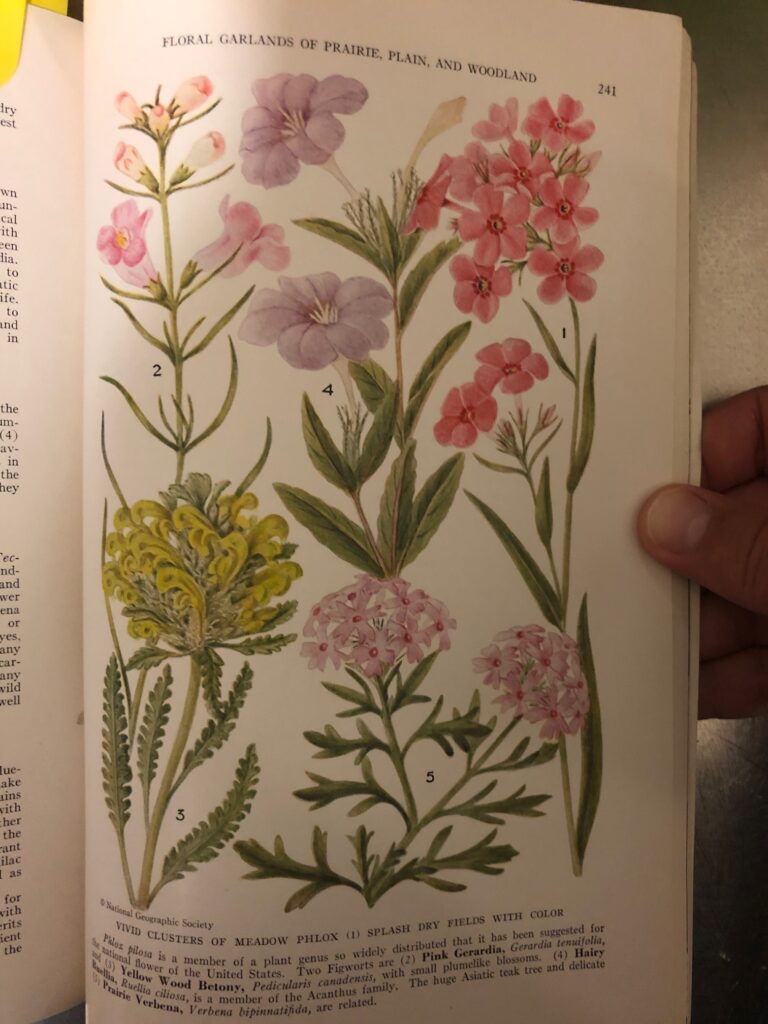

Blosum, painting angrily against the emerging Pop artists in 1961, copied the prairie, plain, and woodland flower paintings of noted botanist Edith S. Clements. Clements, with her husband Frederic, had published one of the most influential guidebooks to wildflowers in the country in the 1920s, but these particular paintings and evocative descriptions came from the August 1939 issue of The National Geographic Magazine. 125 paintings filled 25 full-color pages, interspersed with poetic, sometimes unusually anthropomorphic, accounts of each species’ traits and behaviors.

All of Blosum’s blossoms are here, and the captions, too, including one line from Wordsworth. The only difference is this work at Karma, to which he added, “a gay king.”

Which reminds me that in just a couple of years, Andy Warhol, the gay king of all gay kings, would also crib the magazine images of a prominent woman–in his case, Modern Photography editor Patricia Caulfield–to make Flowers paintings. Karma indeed.