The Casino di Villa Boncompagni Ludovisi in Rome is for sale, and the hook for media coverage is not the Guercino painting in the foyer of radiant Dawn riding her chariot across the glowing sky that gives the house its nickname, Villa Aurora. Instead it’s the oddly composed mural on the ceiling of a small upstairs room, the only mural painted by Caravaggio.

It has been appraised somehow at EUR310 million, which helps bring the opening bid for the auction of the former hunting lodge on a half-acre hilltop next to the Borghese to EUR471 million. The Italian state has the right to match any winning bid.

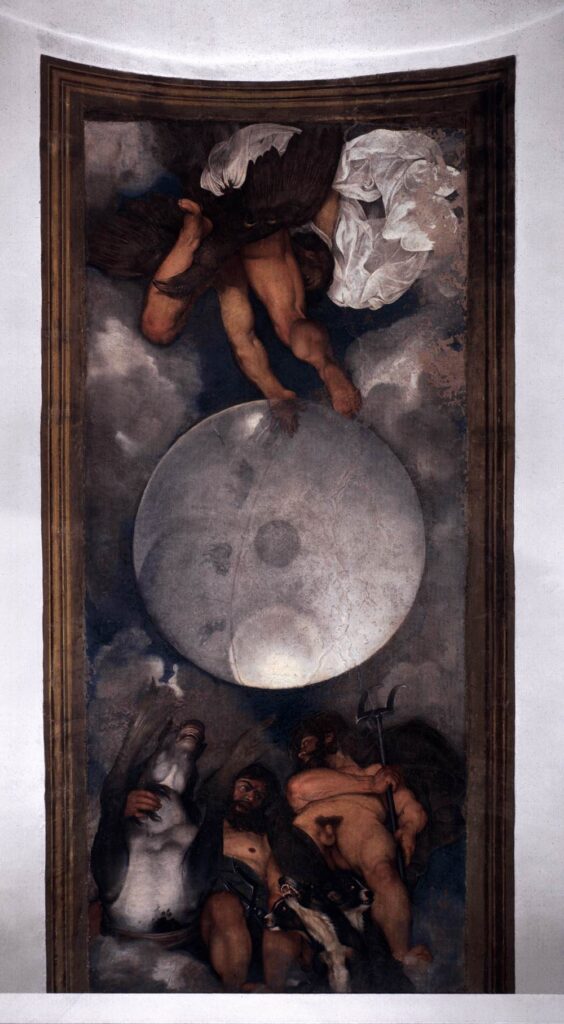

The mural is purportedly on the theme of alchemy; the room it inhabits was initially a laboratory, and housed a distillery. It depicts a celestial sphere flanked by three nude gods, Jupiter, Neptune & Pluto–the model is the artist himself, who was 25 years old in 1597–letting it all hang out in extreme perspectival, toga-less majesty.

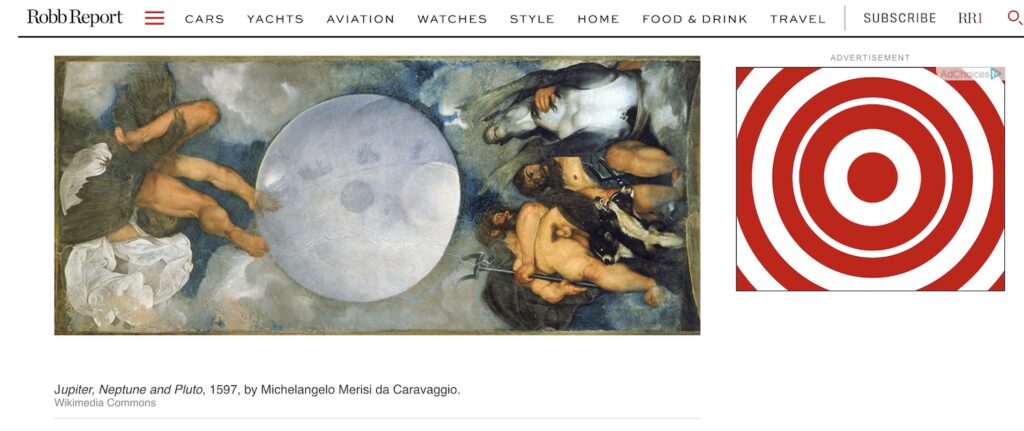

Which prompts two questions, one historic, one contemporary: what are the circumstances under which a 25-year-old emerging artist paints himself nude, three times, towering over the viewers below? And why is it so hard to figure out which way the mural is facing? Because it is reproduced in both orientations almost equally.

Last one first: balls-out Caravaggio as Pluto is shown on the left in The Guardian, Wikipedia, artnet, The Robb Report (an ARTnews/Art in America sister publication focused on the wealthy wack, and whose perfect contextual ads win the screenshot contest) Getty Images, and even in The Lives of Caravaggio, a collection of reissued historical biographies of the artist published in 2019 by the Getty Foundation.

It is interesting to see that Alamy, another stock photo company, has multiple, identical images of the mural, in both orientations, though only one is labeled as “flipped.” This might impact peoples’ decision on which image to use.

It is also interesting that several outlets credit Wikipedia for their image, and Wikipedia itself credits Web Gallery of Art. But the photo on wga.hu faces the other way, and also captures the curve of the ceiling vault, and a plaster beam that gets in most photographers’ way. This orientation matches instagram user @rachov’s post from his tour of the villa: Pluto stands on the right side.

How could this happen? I think most people haven’t seen it. That includes most art historians, and most everyone who’s written about it. It was covered and forgotten until the mid-1960s. It’s been essentially inaccessible in a private villa before and since. Public access only really began in like 2010, when Princess Rita, the third wife of Prince Nicolò Boncompagni Ludovisi, began offering private tours once a month–for EUR300. It’s Rita’s dispute with her stepchildren over her late husband’s estate that is forcing the sale.

Out of sight, out of mind, out of history. This mural has largely gotten the shaft from those who have written about it. But as I think about the first question, I wonder if that’s a mistake? How did Caravaggio come to paint three nude self-portraits as Roman gods on the upstairs ceiling of a private hunting lodge in what was then the most magnificent garden in Rome?

Because the owner of the lodge, the garden, and the massive villa they accompanied liked to fill his private spaces with pictures of beautiful, swarthy, barely dressed young men. In 1594, when Caravaggio was 23 and just striking out on his own, his painting of young, pretty, expensively dressed hustlers, known as The Cardsharps, was purchased by that Florentine noble, the Cardinal Francesca Maria del Monte, who soon invited Caravaggio to move in. The artist lived in the Cardinal’s household for five years, producing for del Monte a series of intimate beefcake paintings that made his reputation: The Musicians, The Lute Player, Bacchus [above], Boy Bitten by a Lizard, and, of course, the ceiling mural.

Del Monte would soon arrange the church commissions to paint the pair of giant, naturalistic depictions of St Matthew in the Contarelli Chapel that made Caravaggio the most renowned painter in Rome. The artist moved out of the Cardinal’s place when he was 30, and the went on to live the rest of his short, remarkable career, and his tumultuous life. He died in a fight in 1610, just 38. Del Monte had the murals to remember him by though, at least until 1621, when he sold the property to Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi and moved back to Florence.

The auction for the Casino di Buoncampagni Ludovici will be held in January 2022.