Every time the “The Uffizi sold some NFTs” story flashed in front of my eyes over the last year and a half, my tabs would fill up with factchecking, archival deep dives, and breathless hot takes. And then I would stare at my blog drafts screaming, “lol no!” in my head for a few days before closing everything and moving on. Like the pandemic itself, I keep wishing it was over, while the world around me maddeningly conspires to keep it going.

Money-grabbing NFT stories are all alike; every museum NFT story is money-grabbing in its own way. It does seem like the Uffizi using the existential panic of COVID to minting NFTs of Old Masters was just a datapoint between Global Art Museum dumping the out-of-copyright contents of the world’s museums on OpenSea in the seconds after the Beeple Big Bang, and the British Museum pitching NFTs as souped-up postcards in a gift shop pop-up.

But though the timing was craven, the Uffizi’s venture–or the venture at the Uffizi–was in the works long before the NFT hype bubble. If anything, the company behind the project, Cinello, S.R.L., only tacked NFTs onto the end of their value chain for the promotional hype. [That the NFT-verse only delivered one sale for Cinello before the boom turned to bust shows actual NFT collectors (sic) were not duped, at least not by this.]

Unlike more traditional (sic) NFTs, Cinello’s project is molded in high relief by the Italian cultural institutions they’ve been pressing up against for years. From the cash-chasing hype wrapped in cultural preservationist platitudes; to the distorted view of the digital image tethered to a unique, physical object; to the overpowering obsession with ownership and control, Cinello’s offering was an NFT only an self-interested Italian museum director could love.

What Cinello sells they call a DAW®, a Digital Art Work [Registered trademark]. It is a physical object, a painting-shaped screen showing a high-resolution digital image, with a customized computer on the back, wrapped in a handcarved replica frame, and all encased, it seems, in a freestanding wall [see above]. It is all meant to reproduce the work it references, precisely and at scale, and to provide a fully equivalent experience of standing in front of the real thing.

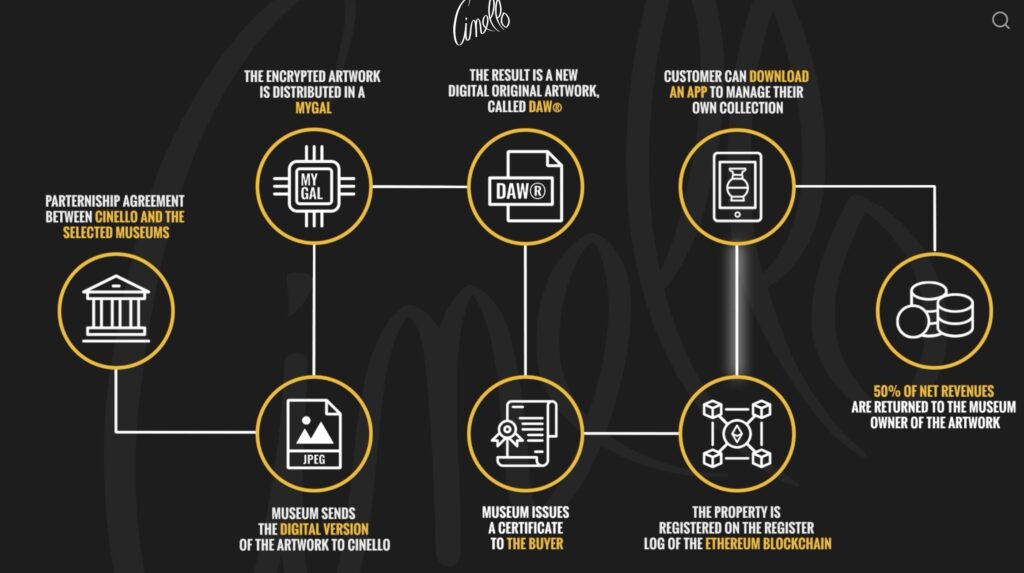

This object is also embedded in a system of authority, monitoring, commoditization and control that uses technology–hardware, encryption, geotracking, network transmission, proprietary exchanges, blockchain–and legal constructs–patents, copyrights, licensing, contractual restrictions, resale clauses, certificates of authenticity–with equal enthusiasm.

The DAW® features described in Cinello’s patent read like the wish list of a bureaucrat running an Italian museum: DAW® is a perfect reproduction of an artwork. It is uncopyable, thanks to unbreakable encryption. The digital image file can be locked down locally, or served remotely via an unhackable network connection. The DAW® can be geo-locked and timed, so it is only visible at a specific location, or for a set amount of time. By constraining an infinitely reproducible digital image, it can be replicated and sold as an exclusively authorized edition.

But Cinello claims a DAW® is not (just) a reproduction. It is a new, original work of art, imbued with an aura of its own, and sufficient to stand in for the originals. Which is literally how Cinello seems to have started. DAW®s trace back to Cinello’s creation of digital facsimiles of paintings for display in Italian museums while the originals were out for shows or conservation. Then they evolved into exhibition copies of irreplaceable works that would never be loaned. In 2019, Cinello organized what they called the first exhibition of Leonardo da Vinci’s work in Saudi Arabia; actually, it consisted only of actual-size digital facsimiles.

The convolutions in their flowchart are the complexity their institutional partners needed to justify the deal, but Cinello’s plan remains unchanged from their earlier version: embed itself as the digital gatekeeper for these museums, and lock in their cut as its DAW®s usurp the original art objects’ place (sic) in the networked, digitized future.

It’s worth noting that when the NFT press was hot, Uffizi officials seemed fine to go along with this scheme, lend their institutional credibility, and enjoy the visionary attention. And as soon as things went south, the museum cut & ran: “The museum didn’t sell anything but granted the use of the image—the sale of the digital artwork is all down to Cinello. It is false to say that the museum sold the Tondo copy,” reported The Art Newspaper.

Claiming DAW®/NFTs were nothing more than an image licensing deal ignores the last year and a half of hype, but also the direct involvement of museum directors in signing “certificates of authenticity” for the DAW®s being sold. If all they’re doing is making a hi-res jpg available, why not just release them to the world, like the Rijksmuseum? Or even just to me? I, too, would like to make a full-scale digital facsimile of a Michelangelo, suitable for framing, to put beside my stock photo pool.