One of the wilder stories I found while researching the Art in America essay on LDS architecture was of the first known photographs of the interior of a temple, which only happened in 1911. That feels late in terms of photography, especially because all four of the Pioneer-era temples in Utah–in St. George, Manti, Logan, and Salt Lake City–all opened in the late 19th century, when photography would have been possible. But though several hundred non-Mormon guests were invited to tour the Salt Lake temple before its dedication in 1893, there was no effort to share images of the interiors of temples with nonbelievers.

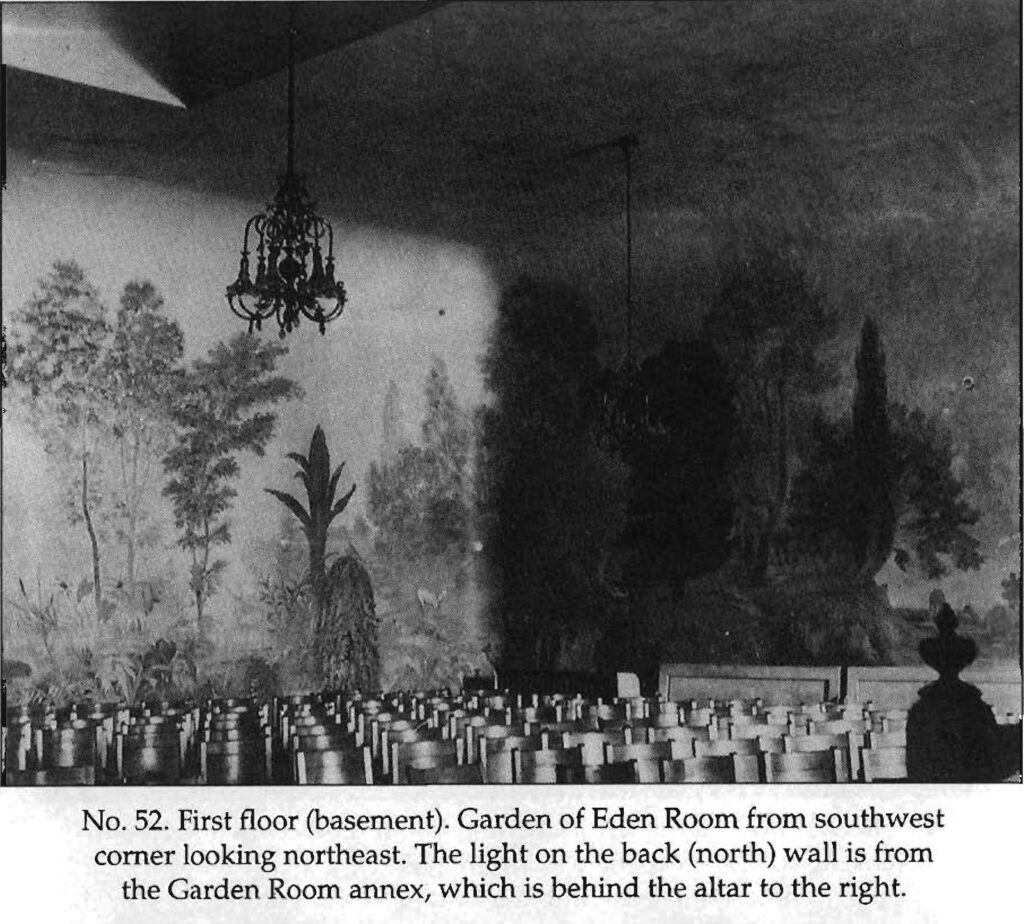

Which is why in 1911 Gisbert Bossard, a disaffected 21-year-old convert from Switzerland thought the Church would pay a lot of money for the 80 or so photos he secretly made by sneaking into the SLC temple while it was closed for maintenance. Bossard got in with the help of a groundskeeper who tended the conservatoryful of live plants in the room that represented the Garden of Eden, and seems to have had the run of the place. Some of his photos included the offices of the church leaders on the temple’s top floor, and the Holy of Holies, a prayer room off the celestial room reserved only for the president of the Church–and Jesus.

After a couple of months of discrete blackmailing proved unsuccessful–and, as close reader @JuliaGoolia points out, after the Church sent someone to ransack Bossard’s house and steal the pictures back, *twice*–Bossard sold an interest in his photos to Max Florence, a former Utah theater operator. In September 1911 Florence sent samples to the Church president, Joseph F. Smith, and then publicly announced the offer to sell the photos to the highest bidder. In a bold move, the Church released the eight sample images to the press, along with their refusal to buy the rest.

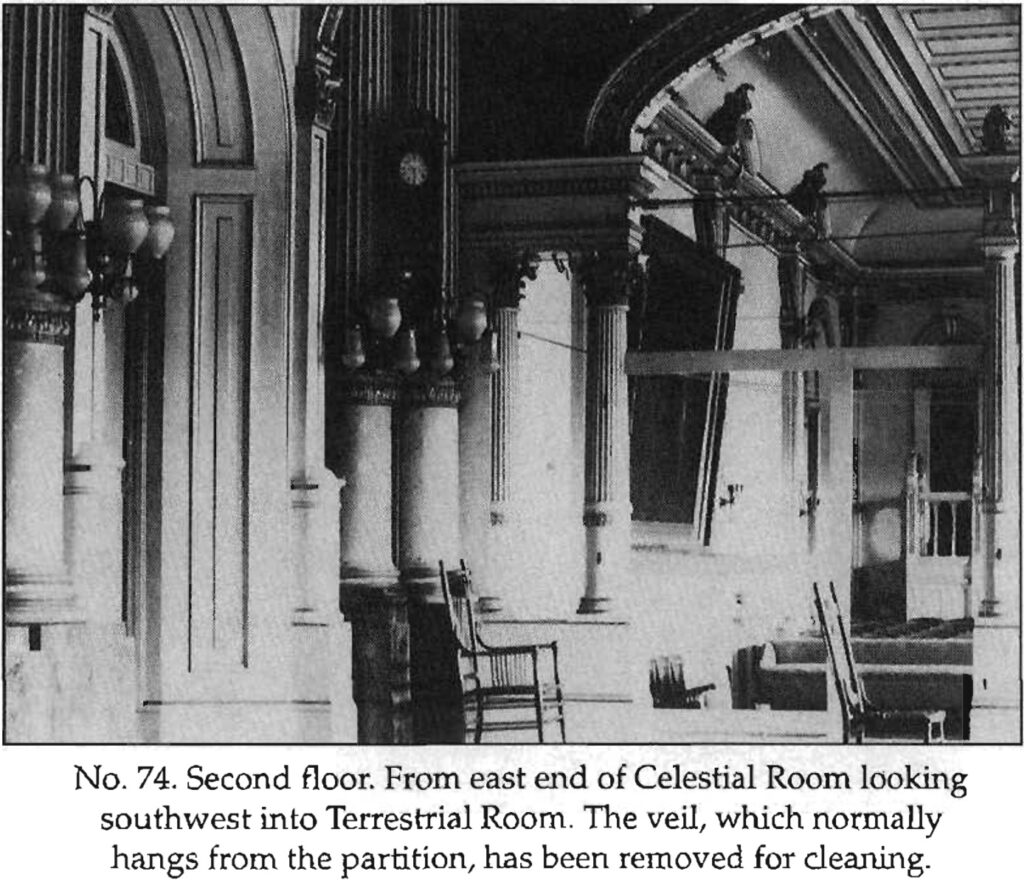

Then Smith announced the Church would release its own photos and an accompanying book detailing the entire interior of the temple, at no cost, basically taking the wind out of the blackmailers’ sails. Sales. Within days, Ralph Savage, son of pioneer photographer Charles Savage, was ushered into the temple to photograph it, while James Talmadge, a Church apostle, rushed to finish the 300-page manuscript for what became The House of the Lord.

In addition to some backchannel negotations with sympathetic journalists, the Church’s counter-PR efforts were probably also helped by the fact that their photos were of much higher quality that Bossard’s. But no one really knew any of that at the time. Except for one nearly empty public lecture in Manhattan, almost no one actually saw most of Bossard’s photos, and their whereabouts was unknown.

Until 1993. That’s when Kent Walgren found four cases of Bossard and Florence’s glass negatives and lantern slides in the library of the Grand Lodge of Freemasons in Salt Lake. No one knows when or how they got there. After adding them to the Special Collections at Utah State University’s Merrill Library in Logan, Walgren published 34 plates in his account of the Bossard incident in the Fall 1996 issue of Dialogue: A Journal for Mormon Thought. [I swear I found the whole batch online somewhere. I’ll keep looking.]

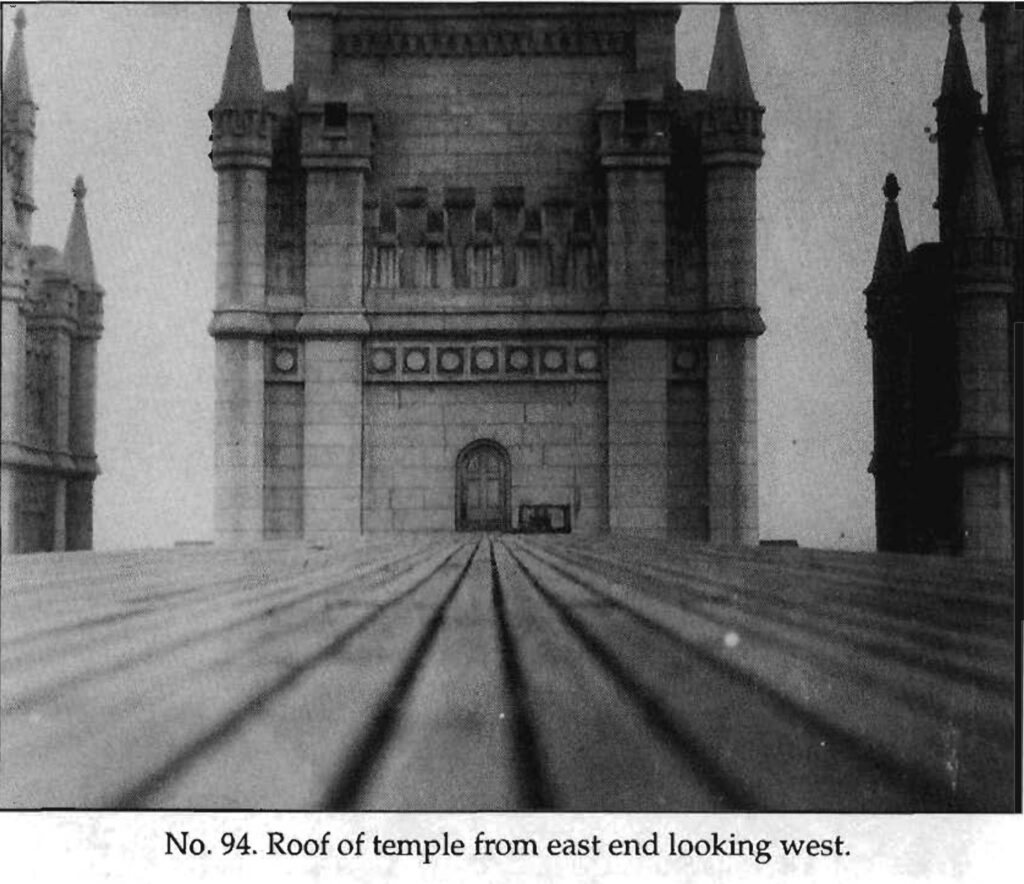

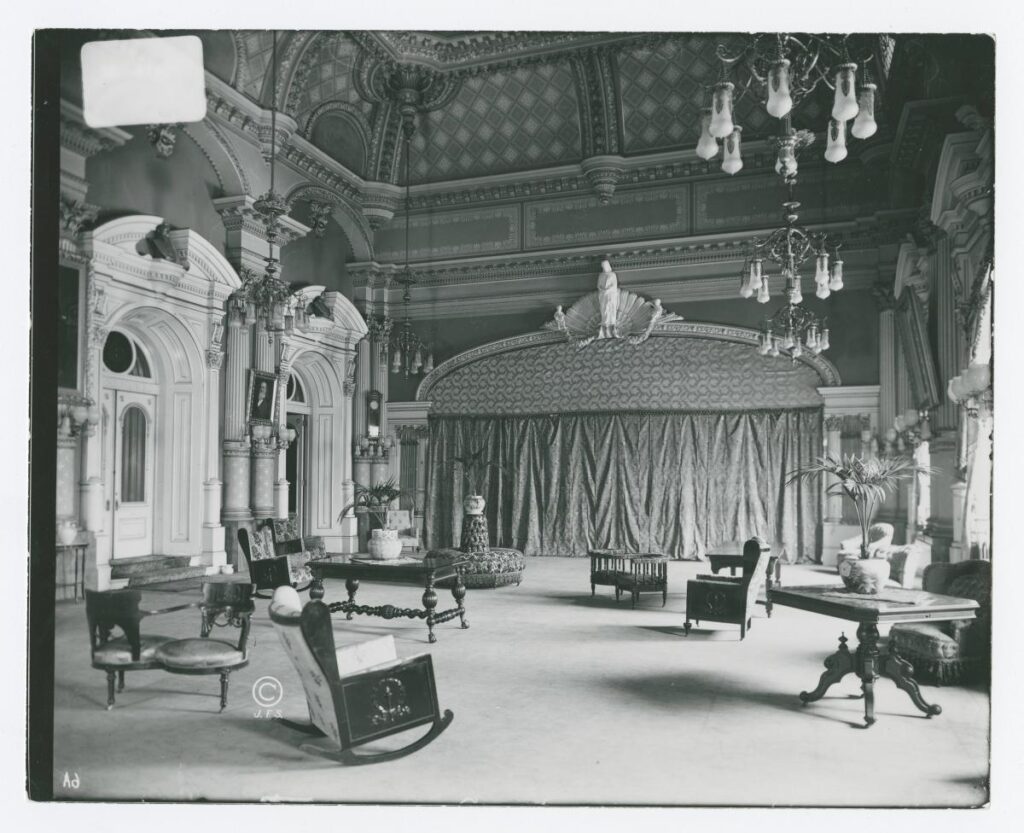

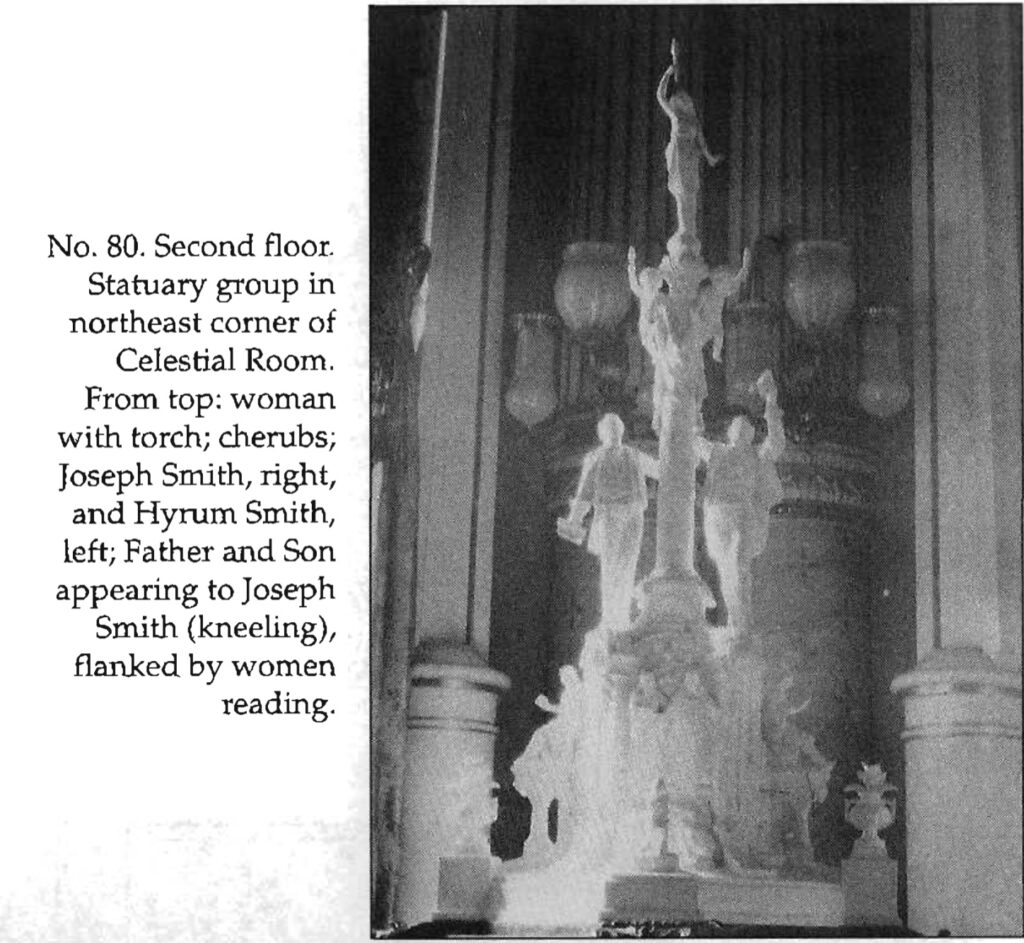

Anyway, I think Bossard’s best photo was not even inside, but on the roof [top], which was a flex. The most interesting, though, was the amazing sculpture which apparently sat in the celestial room for several years. It depicts Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum on a column topped by an angel and surrounded by allegorical figures. On the base is a freestanding/relief combo depiction of Joseph Smith’s First Vision, in which God the Father and Jesus appeared to him. But even this revealing photo was done better by the Church itself.

The artist and fate of this object is unknown, but it is understood to be a maquette for an unrealized Temple Square memorial to the murdered Smiths. Fundraising invitations for a memorial turn up around this time (1911-13), but ultimately, a much more modest sculpture was created by Mahonri Young. Def let me know if you see this in your grandparents’ basement, though.