The Artist Formerly Known As Hilma af Klint was a collective. Documents only discovered in 2021 show that af Klint’s major works were made with a co-equal collaborator (and likely former lover), Anna Cassel, and that together, they led a collective of at least 13 women to produce the paintings that have been considered af Klint’s visionary work alone.

The Artforum from the archives newsletter delivers the news with big how it started/how it’s going energy from Daniel Birnbaum, the art world’s most powerful Hilma af Klint whisperer.

First, from 2013, when he was director of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and about to open an af Klint show:

Is af Klint the first Modern abstract artist? Many have asked this question, but the paucity of known works has kept the answer equivocal. After more than a decade of practicing séances and collective experiments in automatic drawing, in 1906 af Klint initiated a body of work that brings together her skills as a painter with her otherworldly strivings and in many ways anticipates the later, far more famous breakthroughs of abstract pioneers between 1910 and 1913, including Wassily Kandinsky’s first abstract watercolors, Frantisˇek Kupka’s first Orphist works, and Robert Delaunay’s first targetlike discs that resemble af Klint’s totally abstract discs from the following year. Her first series of small-scale nonrepresentative works, “Primordial Chaos,” combines abstract forms with elements that seem to signify the elemental forces of a cosmic creation process, but the next year, in 1907, af Klint had already developed a pictorial language of pure abstraction in which concentric circles and germlike organic forms encounter a strict geometric grid, as in No. 5, The Large Figure Paintings. Although she claimed that her large cycle of works was not really executed by her, but rather by spirits working through her, it is hard not to answer our question in the affirmative.

In 2023 Birnbaum and Kurt Almqvist, both board members of the Hilma af Klint Foundation [until recently, see below], have published Anna Cassel: The Saga of The Rose, essays which sketch out the contours of the collaboration.

From Susan L. Aberth’s Artforum review:

…although it was known that the Swedish artist Anna Cassel (1860–1937) and af Klint were members of the same esoteric circles, most famously Christian spiritualist group The Five, their work together extended well beyond the automatic drawings produced by this female collective. Most significantly, the full extent of Cassel and af Klint’s collaboration on “The Paintings for the Temple”—193 paintings in fourteen series created between 1906 and 1915, planned for a spiral-shaped sanctuary—was not fully understood until the recent discovery, in June 2021, of Cassel’s notebooks and drawings in the archives of Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophical Society in Järna, outside Stockholm. Although af Klint acknowledged that the “Temple” cycle was a group effort, emanating from “a realm inhabited by a plurality of spirits,” the specific details of this coauthorship have long remained unclear. Spirits aside, the editors go on to state the lesser-known fact that “thirteen women were involved in the creation of the physical works” and that because of this extraordinary new information (thirteen!), they acknowledge that research into the collective nature of these works has just begun.

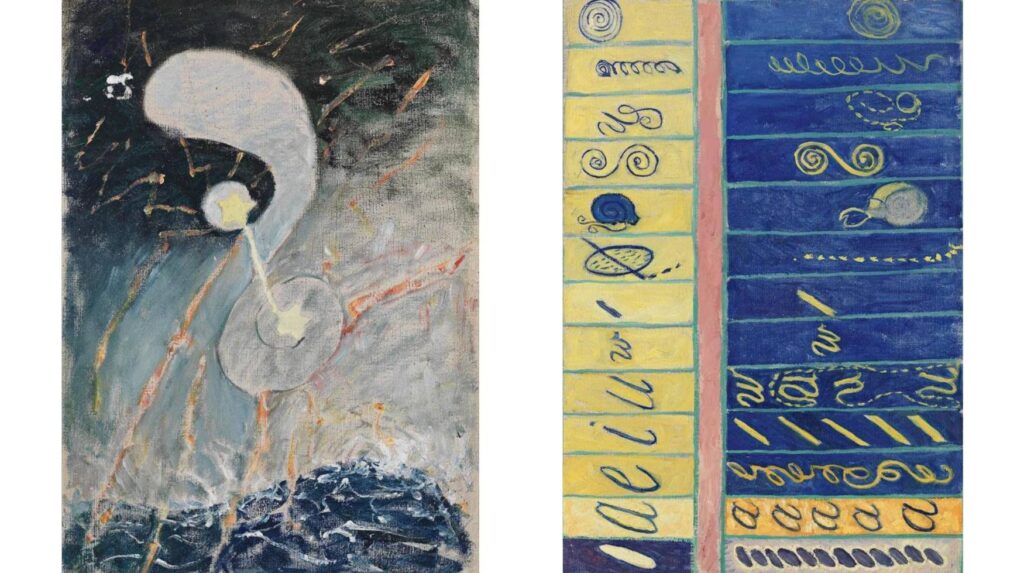

[R] Anna Cassel new hotness: Primordial Chaos, No.10 1906-1907 Oil on canvas. 51.5x37cm.

Image: The Hilma af Klint Foundation, via Engelsberg ideas

The publisher of Anna Cassel: The Saga of The Rose, Bokförlaget Stolpe, has published several podcasts about Cassel and af Klint, their relationship, and the religious/spiritualist context that was central to their painting project. It includes essays and interviews with Hedwig Martin, a scholar engaged in going through Cassel’s 26,000 pages of notes. Martin has so far been able to attribute at least 14 of the 26 paintings known as “Primordial Chaos,” the first group of af Klint’s major project, “The Paintings for The Temple,” to Cassel.

Bokförlaget Stolpe, founded in 2018, is also publishing the Hilma af Klint catalogue raisonné, which I assume will now need an eighth volume. It is part of the Axel and Margaret Ax:son Johnson Foundation for Public Benefit, one of Sweden’s largest private foundations, which is run by Almqvist.

Almqvist and two other Ax:son Johnson-affiliated members left the Hilma af Klint Foundation board in December 2022 after a public dispute with af Klint family members over the sale of 193 NFTs of “The Paintings For The Temple.” The family and the af Klint Foundation board said they had not been notified of the NFT sale, which they said ran counter to the artist’s [sic, artists’ now, I guess] intention to not commercialize the paintings. [The Foundation’s CEO knew about it, though.]

The NFT deal was made between Stolpe, Daniel Birnbaum’s VR startup Acute Art—which also just released a VR version of af Klint’s Temple—and Pharrell’s NFT publishing venture, Goda. The sale brought in SEK2.9 million ($US 282,000). Do Sweden’s richest families really engage in transparently conflicted power moves and self-dealing for so little money? I guess so! Though I’m sure the af Klint NFT bag looked a lot bigger when the deal was being cooked up, presumably in early 2022, before the market collapsed. The af Klint Foundation received zero percent of the proceeds from the NFTs, which were considered a “digital extension” of the CR. They were minted by Acute Art.

How the authorship and reattribution saga will affect the non-commercialization of the af Klint project, or the standing and influence of the Hilma af Klint Foundation, is unclear. But the people leading the effort have locked up all the af Klint authorizations they need; they publish the CR; and now invite you to buy their NFT, their VR Experience, and their book. And there is no Anna Cassel Foundation.

2013: Universal Pictures [artforum]

2023: Spirited Away | Who painted Hilma af Klint’s otherworldly visions? [artforum]