In 2010 MoMA went deep on Cy Twombly sculpture, purchasing five works and receiving two more as gifts. They all went on view the next year, after the artist’s death. On the far right, the Kravises have promised the earliest work, Untitled (Funerary Box for a Lime Green Python) (1954), and the Cy Twombly Foundation gave the sleekest, Untitled (1976), on the left.

Gotta admit, at the time, I did not pay it appropriate attention. In the rough, gestural, elemental, bricolaged world of Twombly sculptures, it definitely hangs back, looking sleek and a bit out of place.

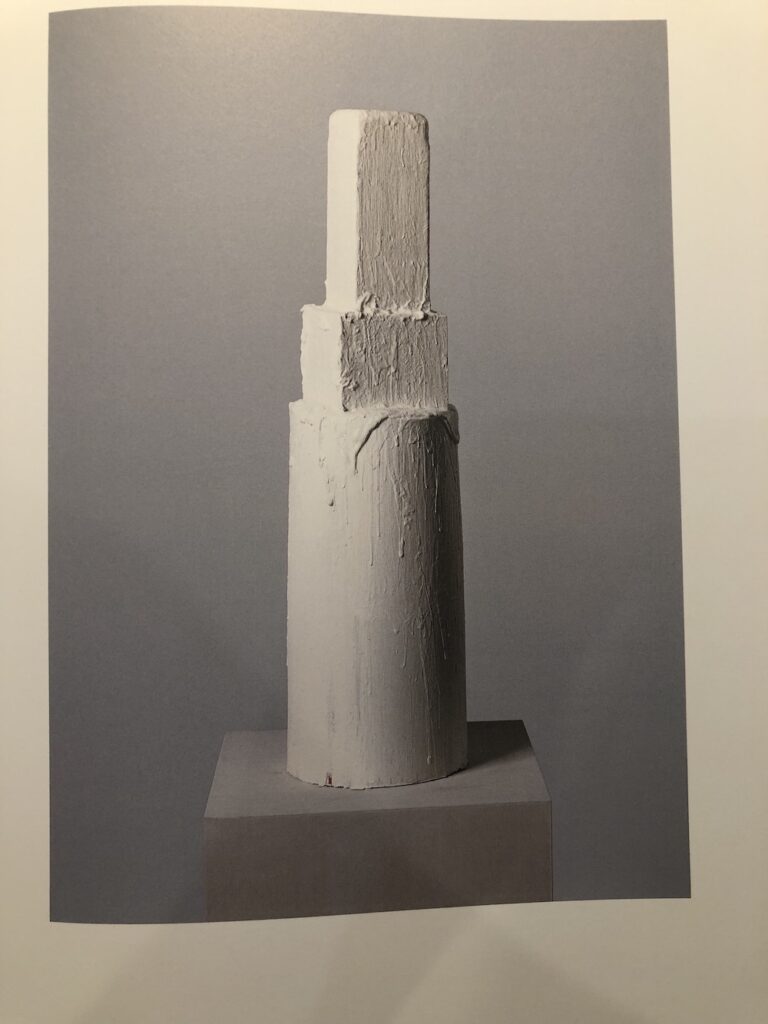

It wasn’t until yesterday, in fact, that I realized there was another. In fact, there are fourteen, but that’s not important now. At some point in 1976, Twombly is sitting in Rome, and he decides to make sculptures again, for the first time in 17 years. Was he looking at the cardboard tubes he stores his drawings in, and he had an urge to stick one in the other, and paint the resulting column white, and then realized, “Oh wow, I’m making sculptures again?” Or was he jonesing to make a sculpture—after showing his 1950s sculptures for the first time in years—at the ICA in Philadelphia, and the closest material at hand was this bunch of tubes?

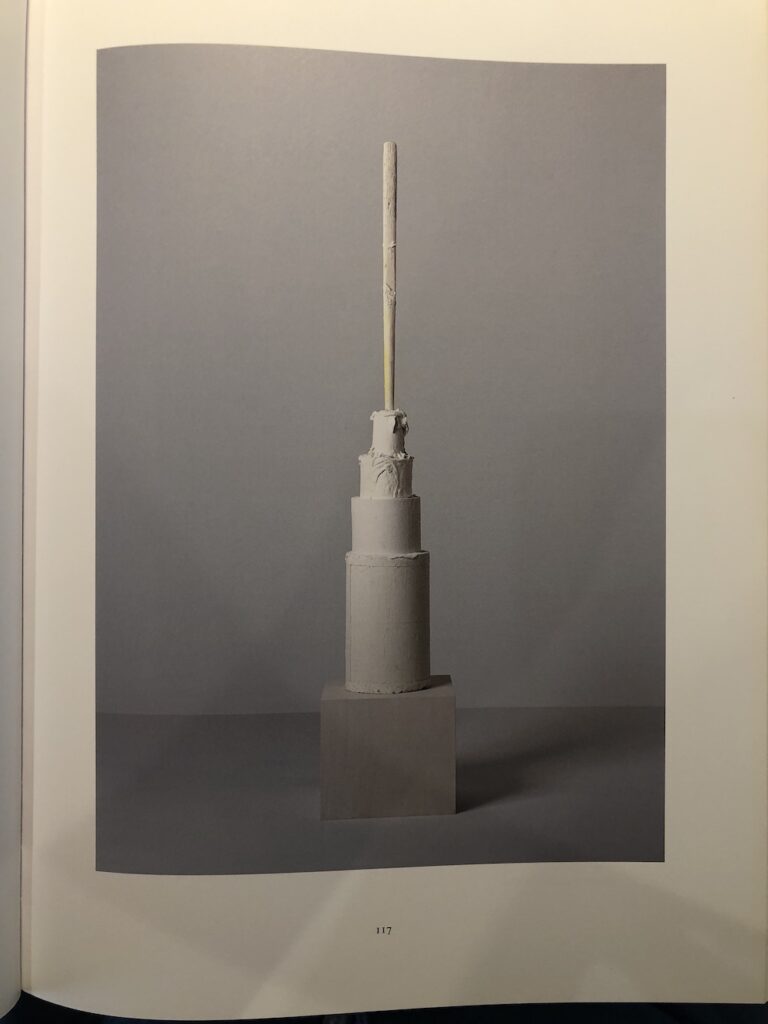

Because Twombly made at least four of these cardboard tube sculptures, of varying heights and diameters. Sometimes he really stuck it in there, and it was 50 inches tall. Sometimes he’d just put in the tip, like the MoMA example, which is the tallest, at 76 inches. To keep it real, he stuck them on the floor.

The catalogue raisonné for Twombly’s sculptures has an essay by Arthur Danto, where he spends most of the time interpreting the palm leaf fan on a sculpture as the wing of a flying swan, and not, as the modernists would have it, as a palm leaf fan. If Danto were to ruminate on this sculpture, what would he envision in order to not see one cardboard tube inside another? A telescope? A lint roller? A tampon applicator? A lipstick? Or would he, like the bot that apparently wrote this Christie’s lot essay, see Pan pipes, ancient marble columns, and Dan Flavins?

A Twombly tube sculpture is for sale in one week. But it is not made of cardboard. Even more than the moment in 1976 where Twombly conceived of these cardboard sculptures, I want to be there in 1977 when he decided to make an edition of them. And when, instead of getting more cardboard tubes, and knocking them out on the spot, he decided to cast two of his completed cardboard tube towers in synthetic resin, in editions of four and six, and then paint those. It is one of these casts, the 5th of the ed. 6, precisely, first sold to Galerie Karsten Greve, then flipped to Amman and Gagosian, that is now to be auctioned in London.

I think these tubes were not only the first sculptures Twombly made in 17 years; they were the first sculptures he decided to cast to sell. For a minute I thought it might be because he was discouraged from putting out works made of such an ostensibly fugitive—also cheap—material. But in the winters in the early 1970s Twombly was visiting Captiva Island, the new studio home of his former squeeze Robert Rauschenberg. Rauschenberg had just made several series of cardboard sculptures and editions, so he knew. Instead, I think Twombly just wanted to keep his sculptures for himself.

This tube sale sent me to the massive, two-volume catalogue raisonné for Twombly’s sculpture, which, again, I have to admit I’d never looked through. It was never at hand. It is frankly stunning and intoxicating, and it makes a compelling argument that no exhibition of Twombly’s sculpture is big enough. The page in Vol. 1 where it goes from a pile of rocks dated 1959 to a sleek, white tube tower feels like flipping from the Old to the New Testament.

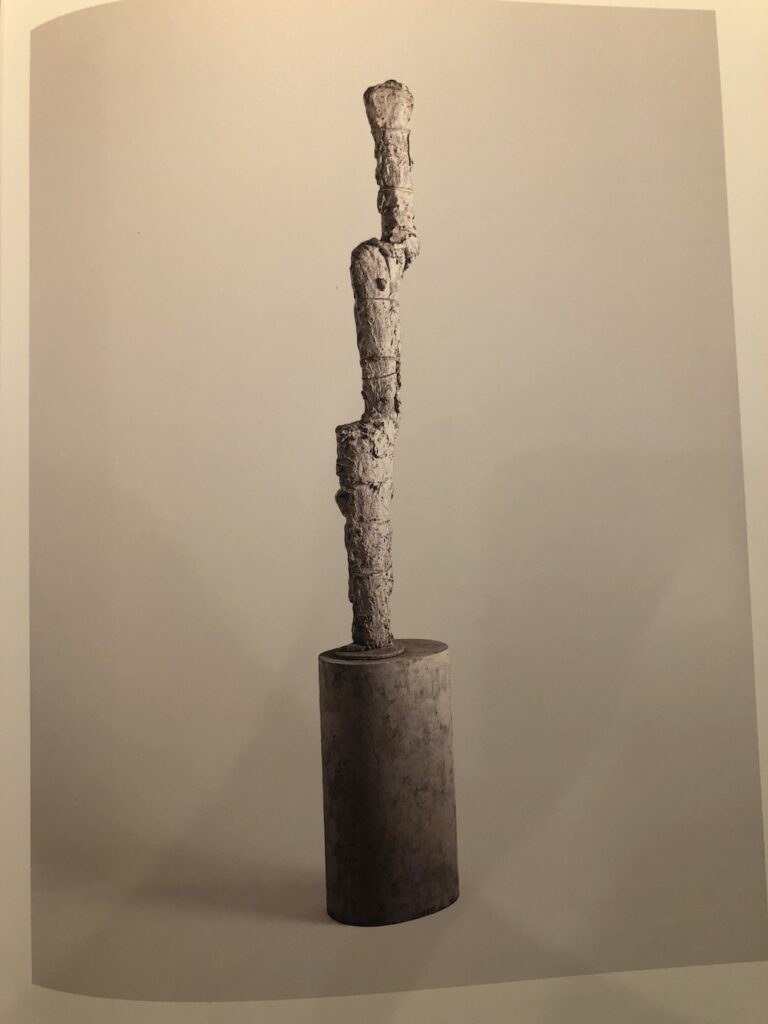

Cylindrical forms appear again, mostly as base elements, in more than half a dozen works in the 2000s. One sculpture from 2009, with a tower of plaster and twine all the way down, was damaged in casting, and only circulates in bronze. But they now have me going back and relooking at the tubes as attenuated figures on attenuated bases. And then their overall human scale comes into focus. The one at MoMA is, like the artist was, 6’4″.