When we last saw Luna Luna, the 1987 art amusement park recently reopened in Los Angeles after spending the last 37 years in a bunch of shipping containers in fields in Vienna and Texas, one thing seemed clear: Drake did not spend $100 million to buy it from its previous owners, the Stephen and Mary Birch Foundation.

But the $100 million price is sort of unfair, a cheat, a third-round shorthand that was meant to get repeated in the same breath as Luna Luna and Drake. When the NYT first half-reported on Live Nation’s project, introduced to them by the Mugrabis, of bringing Luna Luna to Drake, the figure was floated as the “overall investment” that was “approaching $100 million.” What if it was the Mugrabis who tracked down Luna Luna at the Birch Foundation’s ranchette, made a deal for it, and flipped it, Yves Bouvier-to-Ryobolovlev-style, for a nice profit?

The Birch Foundation’s 990 filings with the IRS show that they sold the Luna Luna assets in 2022 for $15 million, $1.8 million below the “market value” carried on their balance sheet. So they actually lost money on their collection of Basquiats, Harings, and their Hockney, Dali, and Lichtenstein pavilions, at least on paper. Not-for-profit indeed. But they did still get $15 million in cash, right? Where’d that go?

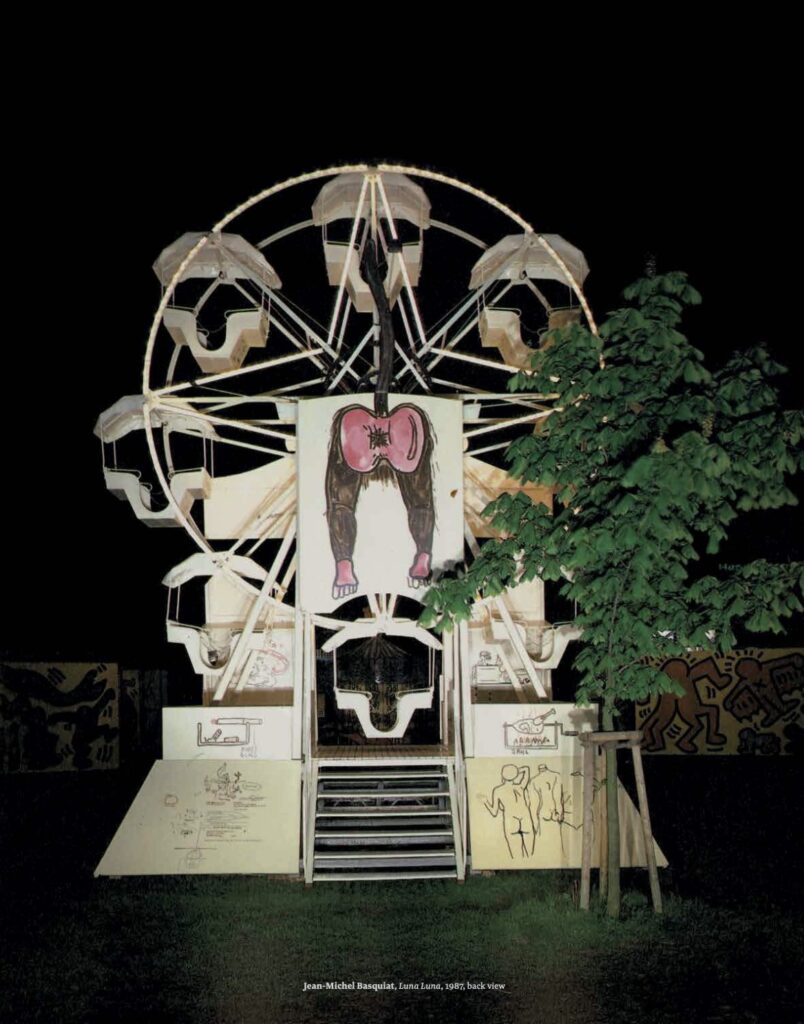

While trying to figure out the details of Luna Luna’s history between its hype launch in 1987 by André Heller, and it’s re-emergence with Live Nation & Drake, two sidebar stories kept jumping into view: the first is Heller’s near miss with forgery charges. Heller tried to turn a minor Basquiat drawing into a major “Basquiat Artwork” by collaging the artist’s little sketches for his Luna Luna monkey butt ferris wheel onto a crude Africanist frame. He sold the work, then scrambled to buy it back when the heat was on, and then tried to blow off the whole thing as a “prank.”

The second, is the giant WTF that is the Stephen and Mary Birch Foundation, and how did they end up with an agreement in 1990 to buy Luna Luna from Heller in the first place? We could ask André Heller, but I think the answer to the first question is also the answer to the second: the Birch Foundation is a giant pile of money and vast tracts of land under the complete and unaccountable control of one or two people who use it for what they want.

OK, maybe not GIANT and VAST, but still, an absolute mountain of walking around money that’s been piling up for 85 years. Stephen Birch was the co-founder of Kennecott Copper, and created the Stephen & Mary Birch Foundation in 1934 to fund hospitals and civic organizations. His son, also Stephen, inherited the 300-acre estate in Mahwah, NJ that, after his death became the campus for Ramapo College.

His daughter, also Mary (Birch Patrick), got Otay Ranch, the 29,000-acre quail hunting preserve in San Diego, and the operating company associated with it, United Enterprises. The houses and lodges on her 35-acre estate, Rancho del Otay, filled up the antiques her brother kept sending her from New Jersey. MBP donated land for hospitals, and sold some; she wasn’t quite a recluse, but she did mind her own business. In 1983 she put together a development deal with her ranch manager and his wife, Patrick and Rose Patek, and then she died. Rose Patek became co-executor of the will, which took over 14 years to settle, leaving 30 heirs hanging. The Patricks together were given control of the Birch Foundation.

While Patrick’s estate was still contested, there were disputes over which assets and proceeds would go to the estate/heirs, and which to the Foundation/Pateks. Understandably, everyone in San Diego was interested in what would happen to 25,000 Otay Ranch acres that had been sold to an Orange County developer, who promptly went bankrupt in 1988, but fought to keep control of the property. [UE held the mortgage, and tried to reclaim the property, but I think they only ended up with like $70 million, around half the original purchase price. Otay Ranch became Chula Vista.] The Birch Foundation gave its biggest gifts during this era when it was needing political and community support in San Diego, including $10 million to build a hospital, and $6 million to the Scripps Institute to build an aquarium. The Pateks and the Foundation were also sued by the heirs for selling land to the Foundation for way below market price. [All this and much more is found in decades of newspaper articles and historical documents helpfully dumped onto a single page by the South Bay Historical Society, which tries to tell the story of Otay Ranch in rough chronological order.]

It is in the midst of all this politically sensitive activity that the Pateks made a deal with Heller to buy his art amusement park for $6 million. In 1991, the LA Times reported Luna Luna would open at Balboa Park in San Diego for 18 months beginning in March 1992, “a gift” from the Foundation. For which it would charge admission. Then after a national tour, the Foundation—which owned and controlled thousands of acres of property—would be “looking nationwide” for a 40-acre permanent home where Luna Luna could expand. This obviously never happened, and Heller spent three years in arbitration with the Foundation in Switzerland, while chasing down actual title to the 28 artworks he’d already sold.

In the earliest available 990 filings, covering the late 1990s onward, the Birch Foundation’s assets swing widely, from. $80 million to $48 million, back up to $83 million, and then peak in 2008 at $221 million. It looks like a ton of real estate, a stake in UE, some shell companies holding more real estate, a bit of corporate bonds, a few stocks, and a bunch of cash & treasuries. And Luna Luna. The Foundation bought hundreds of acres of properties in the north central Texas towns where the Pateks were from. The Patek parents, and one kid, took a small salary, $50k/each, as trustees and officers of the Foundation. Grants ranged from $1.8 to over $4 million/yr, almost all in small amounts to local charities and Catholic organizations in San Diego, Texas, and New Jersey, where another Patek child lived. Also hundreds of thousands of dollars to the Yogi Berra Museum, and then a bunch of pass-throughs to a non-profit the NJ Patek kid set up called Jewels of Charity.

After Patrick Patek’s death in 2007, Rose and the kids jacked up their salary. Since 2008, the Birch Foundation has been paying the Pateks $1-1.5 million/year to trade T-bills, use its land, drive its trucks, and give its money to whoever they meet. Rose only got paid for a few months of 2021, and I haven’t found an obituary, so I hope she’s relaxing in comfort. Her daughter and son picked up the slack, and a chunk of the salary.

The Birch Foundation’s assets were back down to around $100 million when they sold Luna Luna for $15 million in 2022. Converting four dozen rusty shipping containers in a field to cash money should ripple through the Foundation’s operations and accounting. Non-profits are required to file income statements and balance sheets, but not cash flow statements. But though my forensic accounting professor at business school literally wrote GAAP, I cannot for the life of me figure where the money went.

The Birch Foundation pays hundreds of thousands of dollars each year for legal counsel, accounting, and investment management, so I am sure it is all perfectly above board. But it is truly a marvel of our system that a non-profit foundation can be so profitable for the people who control it; that such a sinecure can be inherited—and, apparently, liquidated—just like any other fortune.