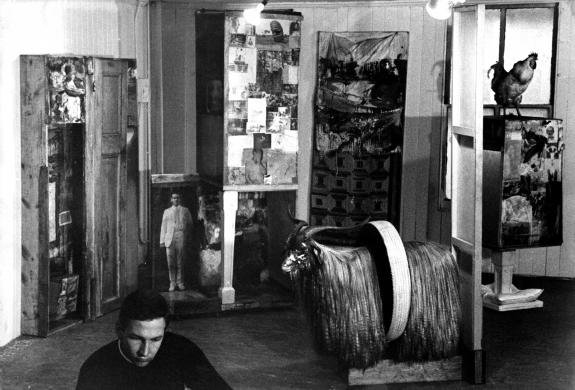

When I saw a print of this 1958 photo of Rauschenberg in his studio in a group of eleven artist portraits by Dan Budnik coming up for sale in LA, I took a closer look at the boring side of the image, which turns out not to be boring at all.

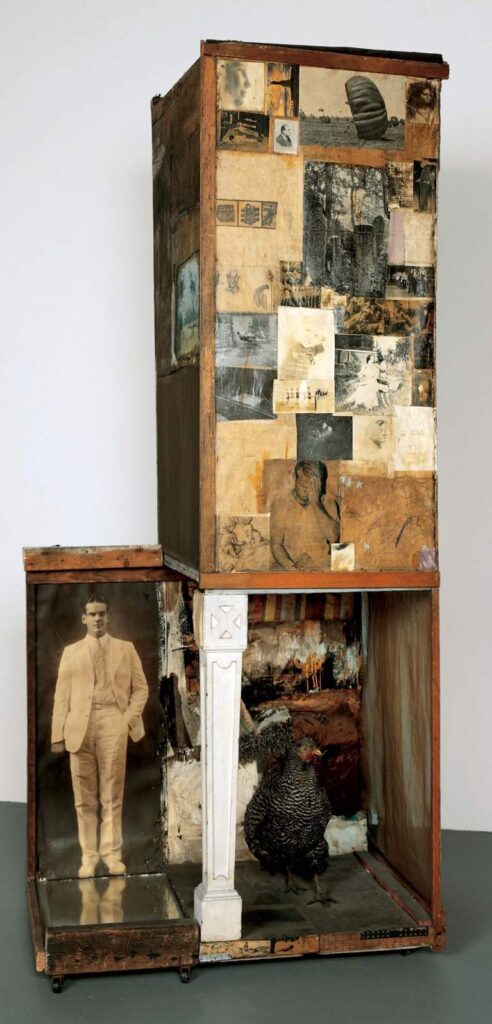

It’s wild to see how bright and red Charlene (1954) was compared to how brown it is now. But it’s the side view [sic] of the untitled combine on the right, variously called Man With White Shoes and Plymouth Rock that feels unrecognizable. I feel like I’ve never registered the blank scrims on this side before, and now looking, I can’t find any images of it. The visual intensity of the rest of the work makes it easy to miss the quiet parts.

But Budnik found them, and lit them right the hell up. He turned the open back of the piece with the painted shoes in it into a lightbox, and then he backlit that stuffed chicken below like it was a George Platt-Lynes model. It transforms the combine’s vitrine and plinth into a stage set, which actually jibes with key elements of the work’s iconography.

This side view was so unexpected, it took a minute to distinguish Untitled as a separate object from the panel to its right, on the edge of the photo. Fortunately, the Rauschenberg Foundation folks knew, though.

That is the back of the second state of Monogram, which means the light on those shoes might be perched on the back of a tire-wearing, taxidermied angora goat. And unlike in Rudy Burckhardt’s photo above, it’s in color.

This photo Kay Harris took in 1958 also shows Untitled and Monogram, and more, obv, but it’s from Front Street. They really do get around. Am I the only one wondering why we have no historical re-enactments of Rauschenberg and Johns trundling down the cobblestone streets of lower Manhattan, pushing a parade of combines on casters from one studio to the next?

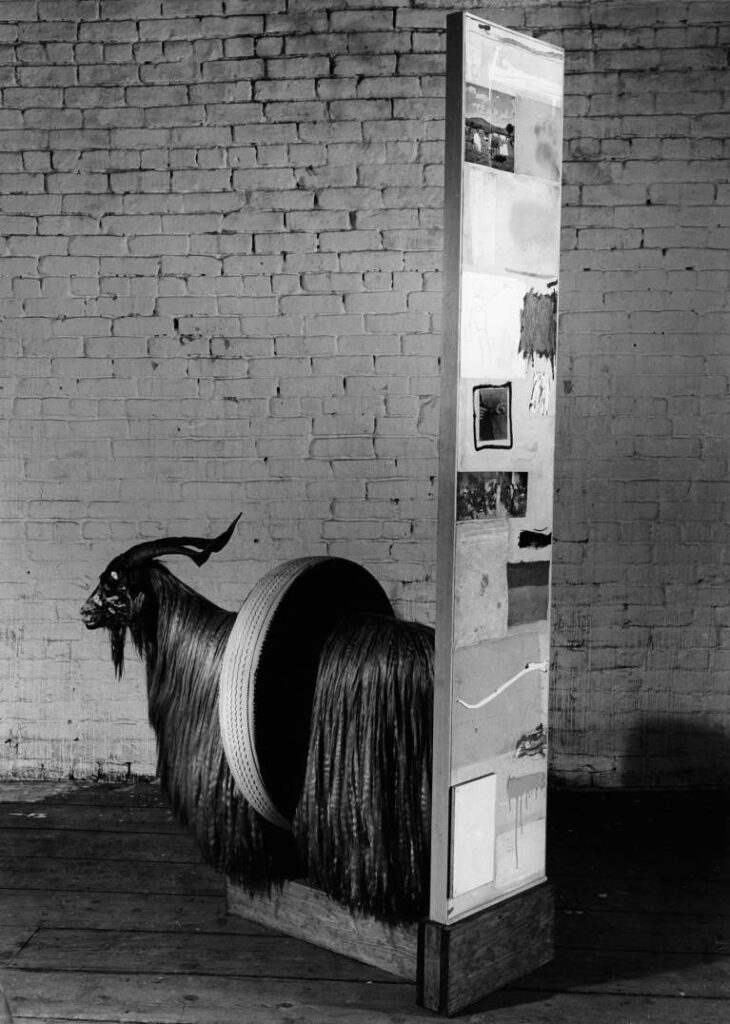

Besides the color, though, Budnik’s photo is also straight-on, which makes it possible to read the back of Monogram more clearly/at all. And I see immediately and specifically, a child’s drawing, paint-pasted above a photo of similarly gesturing hands. I assume, like the sketch of a clown and the plaintive letter on Untitled, which Paul Schimmel discussed in his Combines catalogue, this is a drawing by Rauschenberg’s son Christopher (b. 1951). If so, it’s earlier by a year or two, at least. Which would pre-date the 1956-58 dates generally accepted for the second state. So Rauschenberg didn’t necessarily put the drawing on as he got it; it was already hanging around.

It all really makes me think of how Rauschenberg lived and worked with these works, for years, starting them, adding to them, taking them apart, moving them around, with no expectation or attempt to show them. They all feel interconnected, nodes in a network, that got frozen in form only when they went into public view—unless a flag got stolen or something.

In its first state, in 1955, the goat in Monogram was mounted in profile, on a shelf, midway up a combine panel. Part of that panel become the 1956 combine Rhyme, now at MoMA. What happened to the second state panel is not clear; I can’t find any traces of it being reworked into another combine. But given the way Rauschenberg’s works were made and changed in this period, I have to think it’s out there somewhere.

Previously, related: Robert Rauschenberg, Dad