I’ve had some tabs open for six months about R.H. Quaytman’s work relating to her discovery of an 19th century etching of Martin Luther underneath Paul Klee’s 1920 monoprint, Angelus Novus. That was when I saw a vitrine in Quaytman’s exhibition at Glenstone related to Ch. 29: Haqaq, Quaytman’s Nov. 2015 show at Miguel Abreu, which was a reworked version of her 2015 solo show at the Tel Aviv Museum.

I am trying to make some sense of them by neatly stacking this pile of rubble at the angel’s feet.

Angelus Novus was first owned by Walter Benjamin, and ended up in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The image of Klee’s work has become inextricably associated with Benjamin’s Angel of History, an allegorical figure of progress he evoked in his 1940 essay, “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” But for a variety of reasons, no one had ever considered, or even seemed to notice, the presence of another image sandwiched under Klee’s transfer.

“Engrave,” Quaytman’s catalogue essay [pdf] is a detailed, personal retelling of her experience seeing Angelus Novus in person, and the two years of research that followed her realization. The Tel Aviv show included work related to the scientific examination of Angelus Novus and its material unknowability.

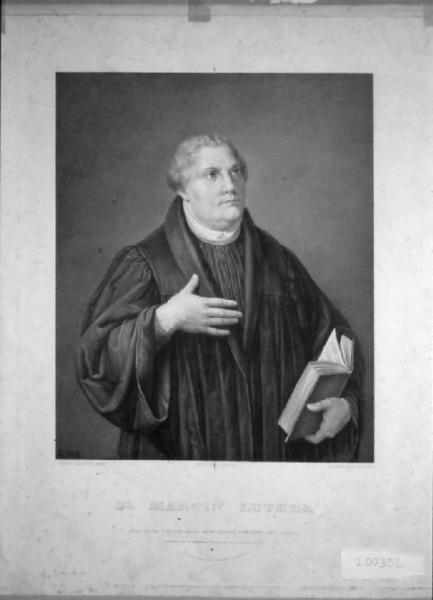

Then in June, two weeks after it opened, Quaytman surfed across the image of the print in a digitized library collection in Lombardi: it was an 1838 etching by Christian Frierich Müller of a 1520 painting of Martin Luther by Lucas Cranach. The New York show included works related to the discovery, and incorporating the Cranach/Müller print. [Re-researching this reminded me that there was a whole NO SPOILERS aspect to the coverage of that show, as if the work was somehow dependent on or about the reveal. Quaytman’s own account, and the work itself, refute that. But it was annoying af.]

It all felt like a trip down memory lane, until I saw Klee scholar and Art Institute of Chicago art historian Annie Bourneuf published Behind the Angel of History: The Angelus Novus and Its Interleaf, which looks at the actual history and circulation of Klee’s work. [Except for getting the title wrong throughout, Hyperallergic’s review is good.] In an interview last September on the Journal of the History of Ideas Blog, Bourneuf discusses the context of Klee’s creation of Angelus Novus and its relationship to Mathias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, both in the time of Luther and in the time of Klee & Benjamin. She rightly notes that, Benjamin’s most famous point about reproduced images notwithstanding, if Angelus Novus were in a collection where it could be more easily seen in person, scholars would have addressed the print much earlier.]

Most interesting, though, is something else that didn’t happen: Benjamin’s failed attempt in 1921-22 to publish a modern culture journal titled Angelus Novus. He conceived of it as “a locus for a kind of Jewish-Christian exchange,” and saw Klee’s figure uniting references to both Grünewald’s resurrected Christ and Talmudic angelology. As Bourneuf puts it, this nuanced, layered history makes Benjamin’s 1940 thesis less a projection onto Klee’s artwork than an ongoing dialogue with it.