When David Platzker first sent me the link to the Brooklyn Museum’s recent deaccession auction, I immediately thought of the phrase, “museum quality.” It has long been used by dealers to sell an object of such stature, manufacture, and significance that it should be—or at least could be—in a museum. How does it work, though, for objects that a museum sells off? Is “museum quality” only now for objects a museum wants to keep? Are these now pieces of “former museum quality”? “Some museum quality”? “Almost museum quality”? Brooklyn Museum Quality.

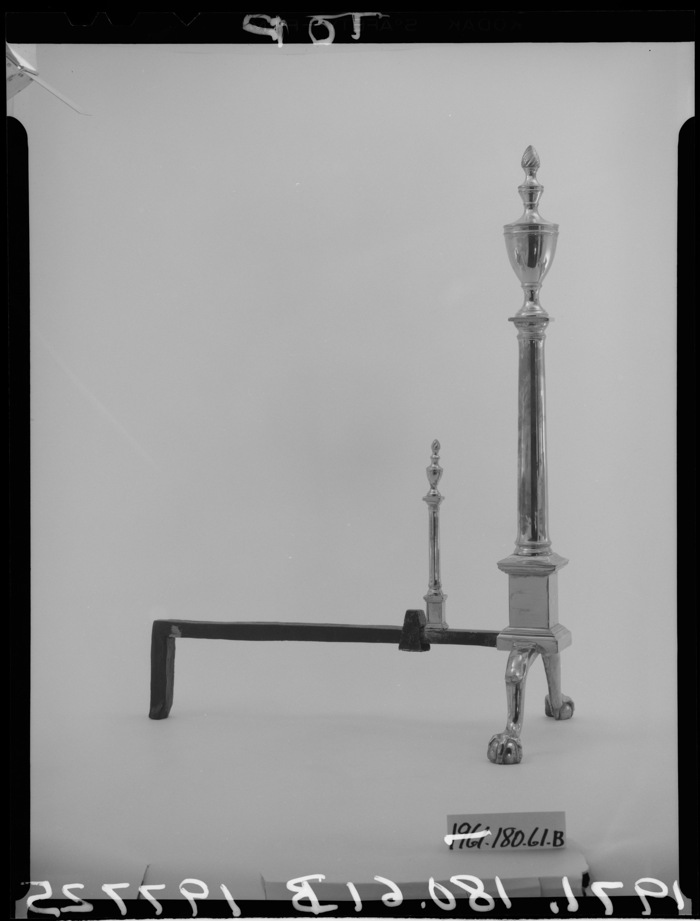

This all came to a head on the first page, when I saw Lot 14, this pair of Federal engraved andirons, estimated to sell for $400-600. Three is a trend, I thought, as I indexed these in my mind against the andiron that started it all—a photo of a lone andiron that turned out to be part of a pair, which was donated to the Metropolitan Museum in 1971 with an attribution to Paul Revere.

And the andirons sold by the Wolf Family last year that matched the Met’s in almost every physical detail, but which had an unbroken provenance and an origin and date that differed from the Met’s. What would these Brooklyn Museum andirons add to this situation, conceptually?

Their date, 1790-1810, and manufacture, “American,” take us away from more specific understanding, not toward it. While they are of an identical type, they are different in enough details—the engraving the swaglessness, the flanges, the feet—that even an amateur andironologist would not suggest they were made by the same hands, the same shop, or even in the same town.

And then there’s the provenance. Though the auctioneer made careful note of the andiron’s physical condition—”one with slightly loose construction and leans slightly to the left”? Who among us, amirite?—the only provenance information provided is the freshest: “Property of the Brooklyn Museum.” I mean, we can guess there’s no conservation history, but whatever object record, accession or donor data, or historical documentation the museum may have held for these andirons is not provided.

Someone clearly knew something, though. Because they paid $41,000 for these andirons, 100x their low estimate, and 5x the price of the perfectly provenanced Wolfs’. People are willing to pay for that Brooklyn Museum quality.