April 18th, 2025 was the 250th anniversary of the lighting of the lanterns in Old North Church, which signaled to fellow patriots across Boston Harbor that British troops were on the move. Political historian Heather Cox Richardson recounted the incident in a riveting and inspiring talk at the Old North Church.

Her emphasis was on the ordinariness of the people involved, and the seeming smallness of their actions, even though they faced real, dangerous consequences. This is all the more important now as we ourselves are confronted with choices to do the next right thing without assurance of the impact. [the YouTube channel that posted video of the speech could not be more random, and its nascent virality is leading it to be reuploaded, so I’ll watch to keep the most authoritative version here.]

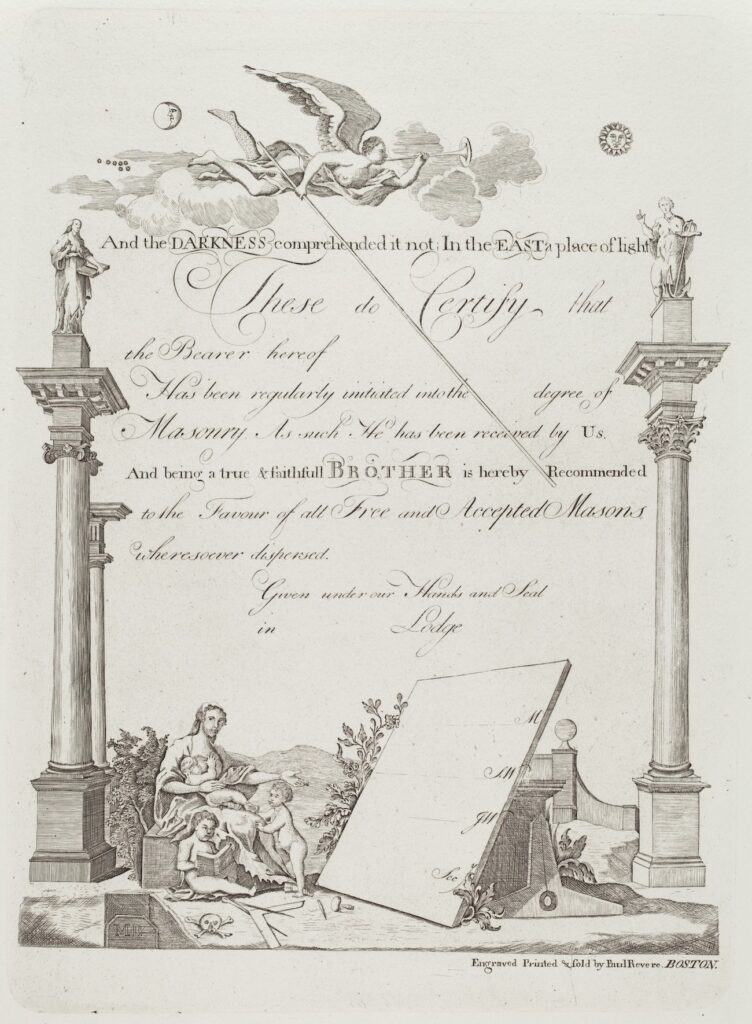

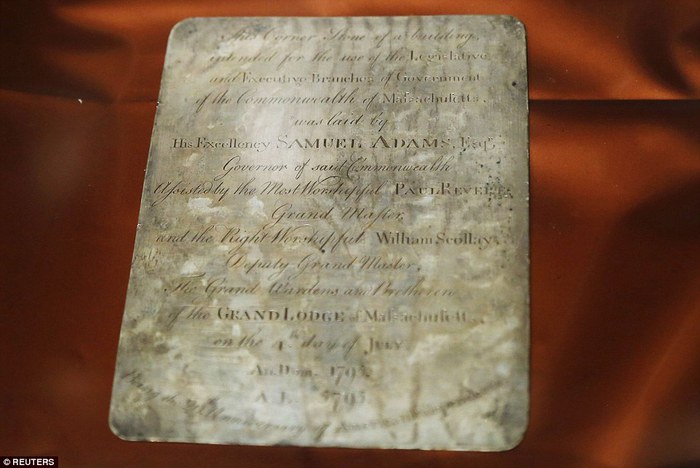

The star of the “one if by land, two if by sea” story is Paul Revere, but Cox Richardson gives full attention to his collaborators, John Pulling, Jr. and Robert Newman, who had access to the Old North Church and who actually lit the lanterns. [As a keyholder for the church, Newman was arrested the next morning, and Pulling bounced to Nantucket.]

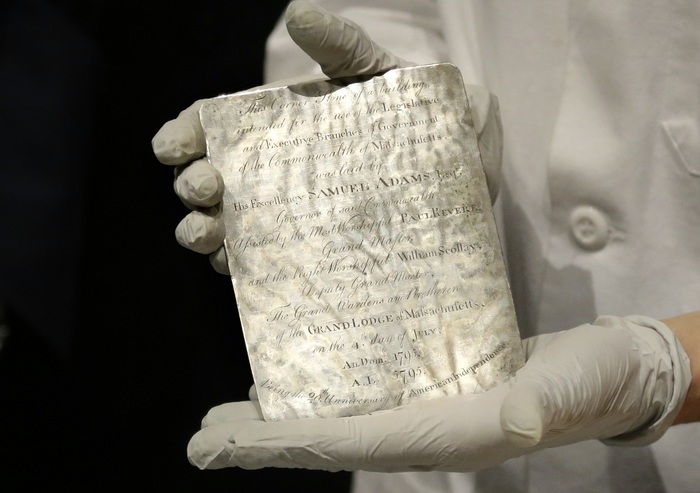

The seeming insignificance of a particular action of resistance was on my mind when Liz Deschenes posted a picture of the Sons of Liberty Bowl on instagram today. Conceptually, at least, I’m a Paul Revere engraving fan, but I confess, I’d never given the Sons of Liberty Bowl much thought. And despite what the MFA Boston says, if you had asked me to tell you the nation’s third “most cherished historical treasures after the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution,” I would never in a million years have said the little punchbowl Paul Revere made for his friends.

But we are in different times, and have a different relationship to tyranny than we did even a few months ago. And it has been worth giving the bowl a new, closer look.

Continue reading “We’re All Paul Reveres Now”