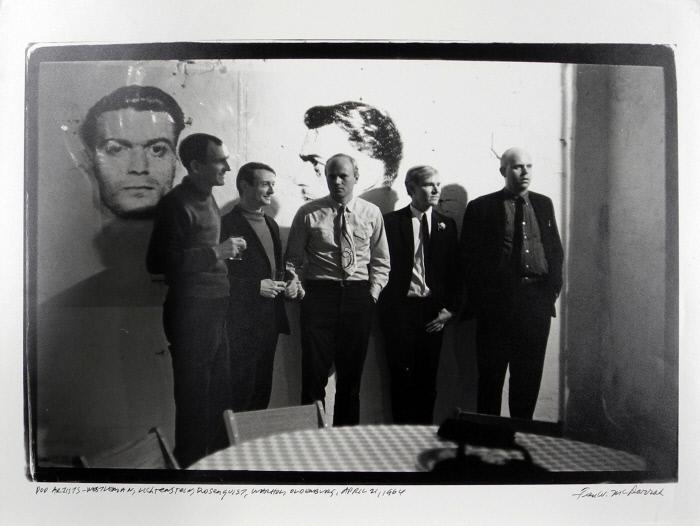

Here is Fred McDarrah’s photo of Andy Warhol partying at the Factory on April 21, 1964, the night of the opening of his Brillo &c. boxes show at the Stable Gallery. The Sculls threw the party, even though it was at the Factory. That’s, from left, Tom Wesselman, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, Warhol, and Claes Oldenburg. Behind them is a diptych of mugshots from Warhol’s New York Pavilion mural, Thirteen Most Wanted Men, which had been destroyed just days before this photo was taken, and before the World’s Fair even opened.

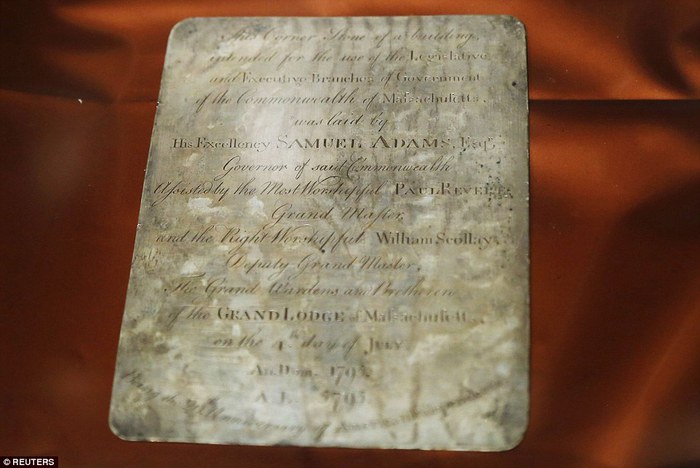

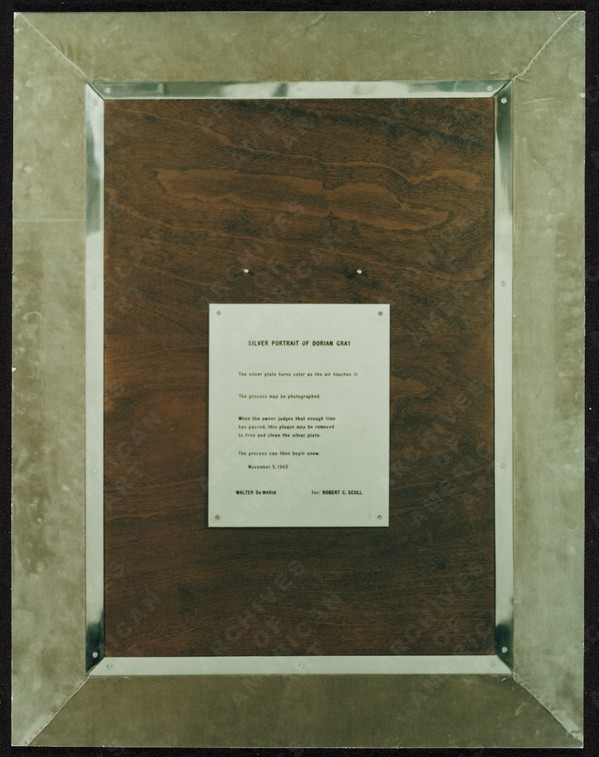

I’ve never been satisfied with explanations of why the mural was painted over with silver. But I blame pavilion architect, art curator, and unremorseful nazi Philip Johnson, who knew the subject–mugshots from an NYPD brochure–told Warhol to keep quiet about it, and then apparently caved within a day of the publication of a Fair preview by a Hearst-owned tabloid that criticized the mural as “Thugs at the Fair,” in which an NYPD spokesman questioned how Warhol had obtained these internal police documents.

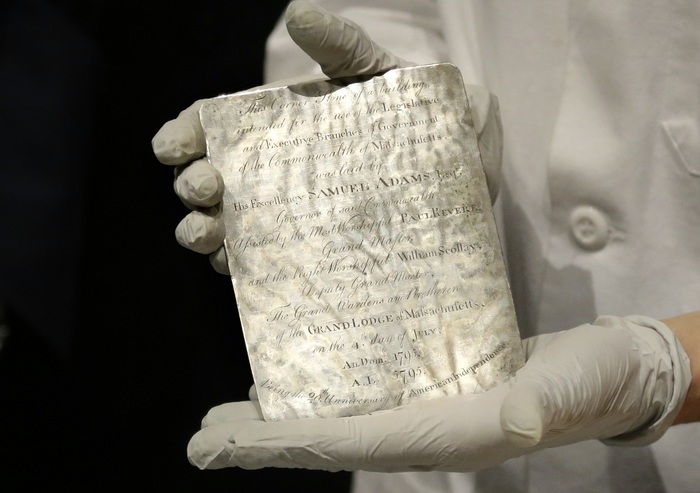

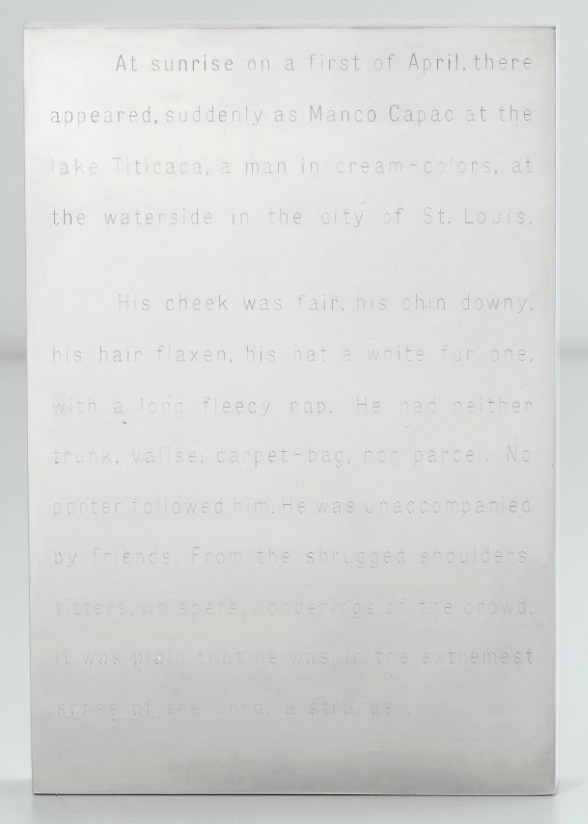

On Friday, April 17, after two days of who knows what, Warhol sent an unsigned, one-sentence letter to the New York State Department of Public Works, Division of Architecture:

Gentlemen:

This serves to confirm that you are hereby authorized to paint over my mural in the New York State Pavilion in a color suitable to the architect.

Very truly yours,

Andrew Warhol

via “Letters to Andy Warhol,” a 2016 Cadillac as in car exhibit [?], cited by warholstars

The architect apparently decided silver was suitable. I think the Times ran this image on the 17th, so the letter was just ex-post-facto CYA. In the aftermath of the mural’s destruction, Warhol decorated his party with images from the project he’d worked on for almost a year and a half. The dates are otherwise unclear, and I haven’t read The Biography*, but Warhol had moved into the Factory in November 1963, and maybe it was painted silver by April, too.

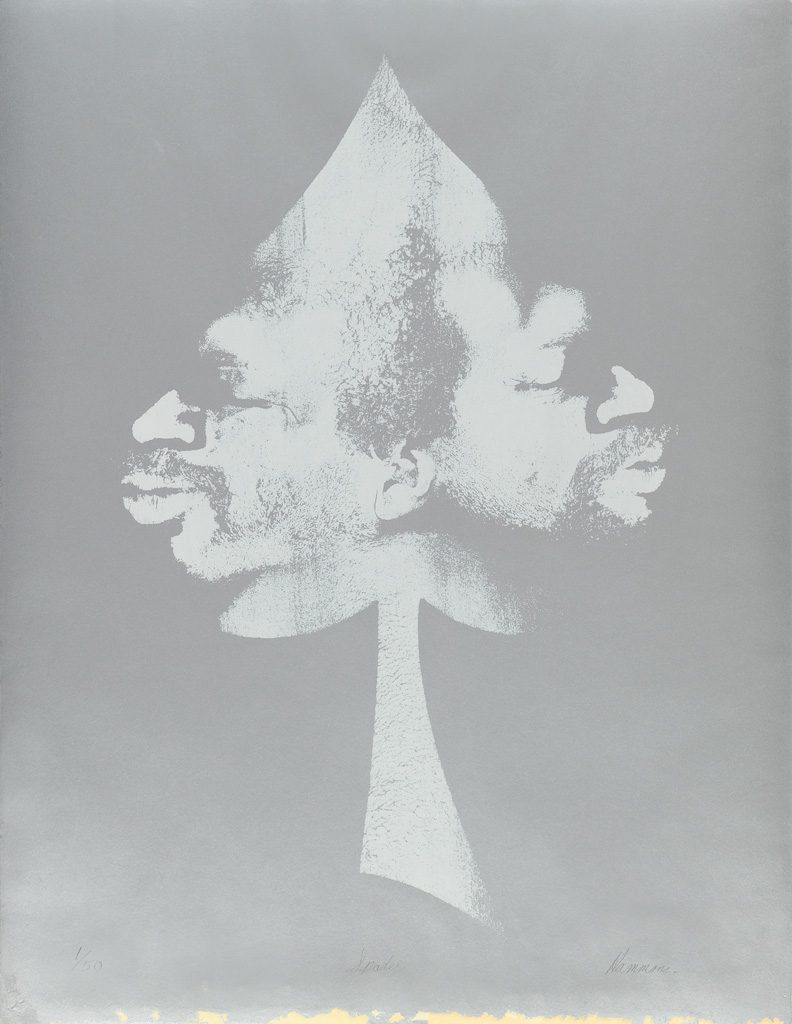

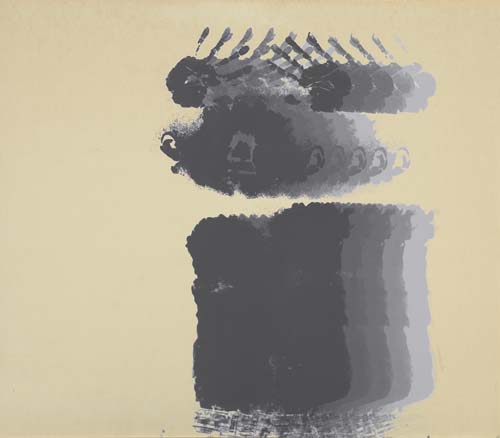

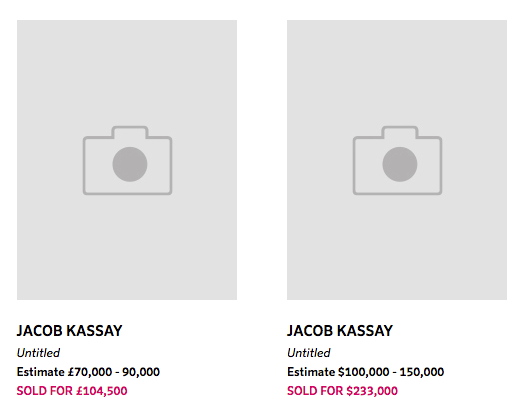

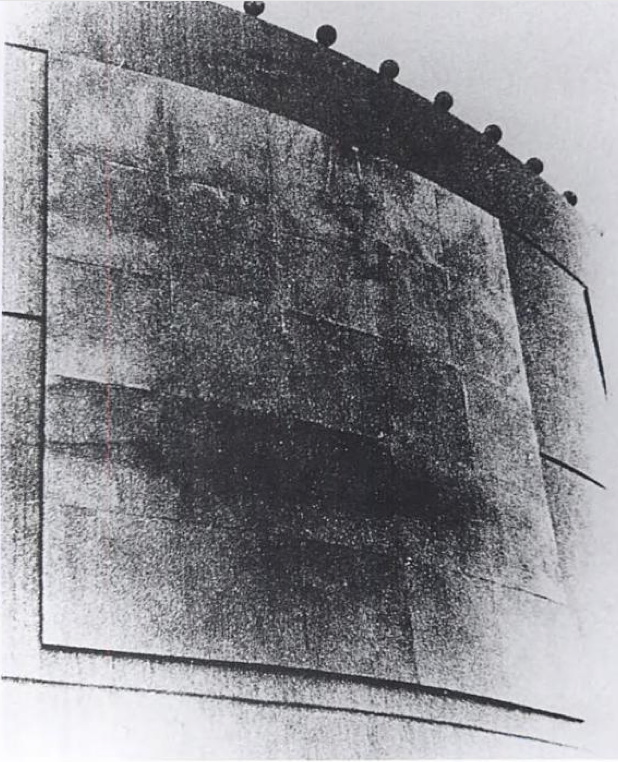

But the images are reversed. [This perp is center right on the mural.] And it looks like a double register. This other McDarrah photo from a second earlier, a print of which is in the collection of the Nasher Museum, shows light reflecting off the mugshots. These are not double-printed outtakes, but the full-scale transparencies used to make the screens, casting shadows on the wall behind them. These ghosts of the mural destroyed just a couple of days before were now decoration for Warhol’s party.

Almost three months later, the Times is still on it, and Warhol feels the need to say the mural was painted over because one guy was pardoned, and so it’s not valid anymore, and he’s working on inspiration for a replacement. That was in July, when he went to the trouble of making 25 panel portraits of World’s Fair commissioner Robert Moses, which were rejected in some paper trail-less way. And which cannot be random; did Philip Johnson pin the blame on Moses? Another, much later conversation used to explain the destruction had Henry Geldzahler and Johnson citing Nelson Rockefeller’s fears of offending Italian American voters in an election year. If that was his choice, between Rockefeller and Warhol, is there any question which way Johnson would go? When the chips were down, Johnson loved power more than art, and he threw Warhol and his rough trade artwork under the bus of New York politics.

Anyway, I now think more about how this must have sucked for Warhol, who spent so much time before–and after–having to destroy his biggest project to date. Not sure what to do with my sympathy for him, except to recommit to bringing his destroyed mural panels back into existence.

- Update: Blake kindly shared the section of his Warhol biography dealing with the mural [my copy is inaccessible atm in storage], and basically all this is in there and more, including: the newspaper column by the highly influential Jimmy Breslin singling out the mural for Archie Bunker-grade criticism basically as soon as it went up; a fierce anti-gay crackdown across the city in the run-up to the Fair; the menu for Wynn Chamberlain and Warhol’s dinner where the most wanted idea came from; and so much more. Thanks!

- Update a month later: and I found my copy of Larissa Harris’s exhibition catalogue, and slowed down to read it, and of course, it’s all in there, too.

Gary Comenas pieced together a lot of this timeline from the Warhol Archives and CR [warholstars.org]

previously, very much related: On Warhol and the World’s Fairs

13 Most Wanted Men exhibition at the Queens Museum in 2014 [queensmuseum.org]

Buy Blake Gopnik’s Andy Warhol biography via bookshop [bookshop]