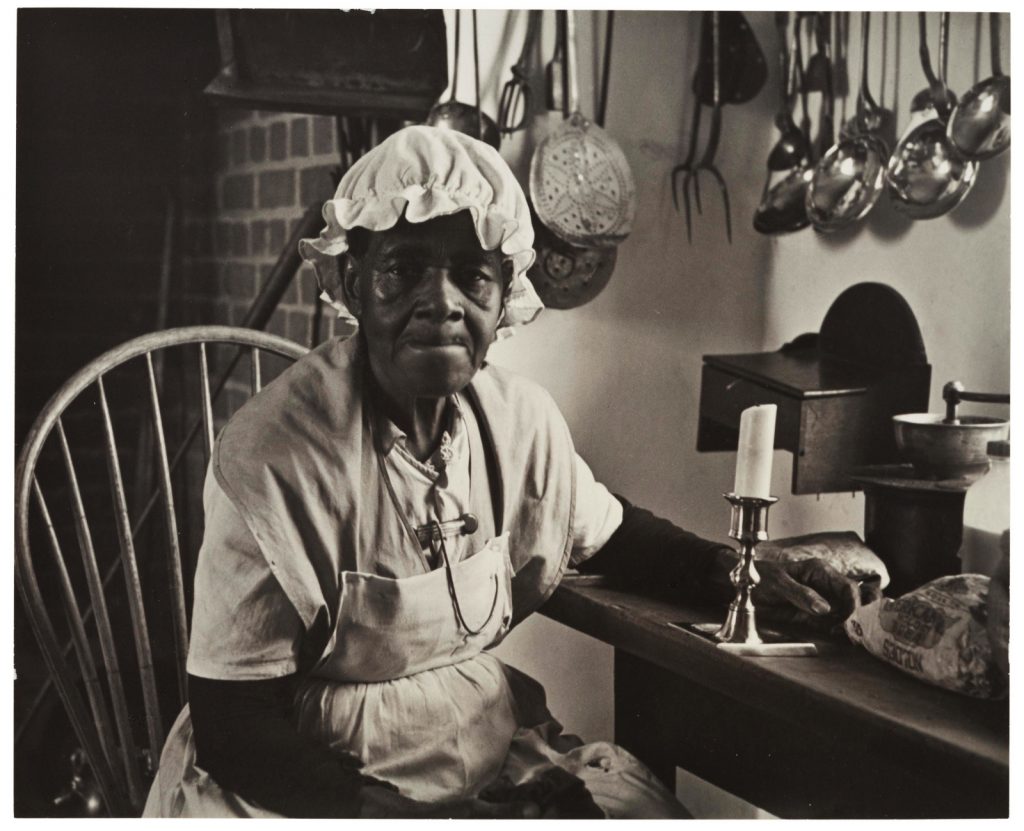

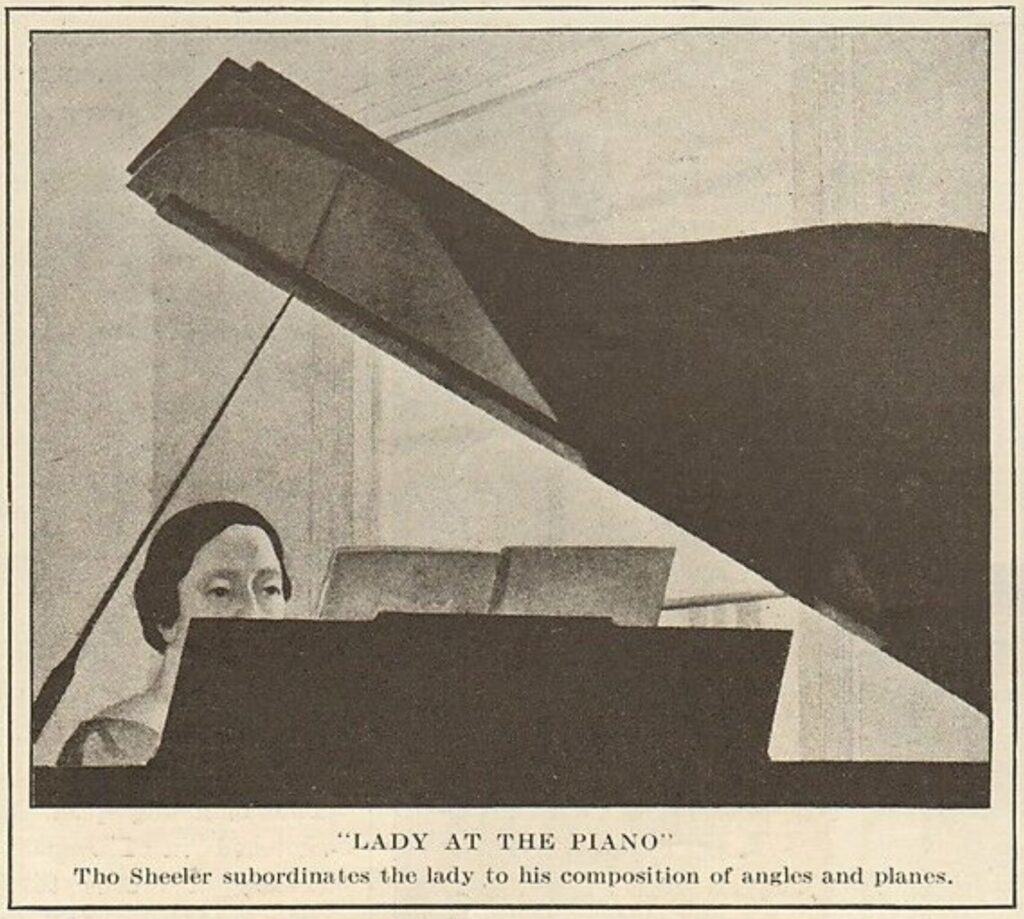

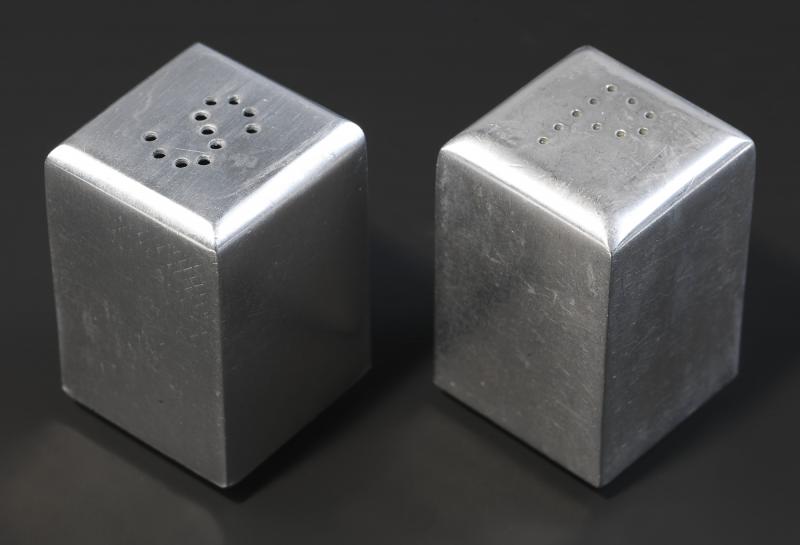

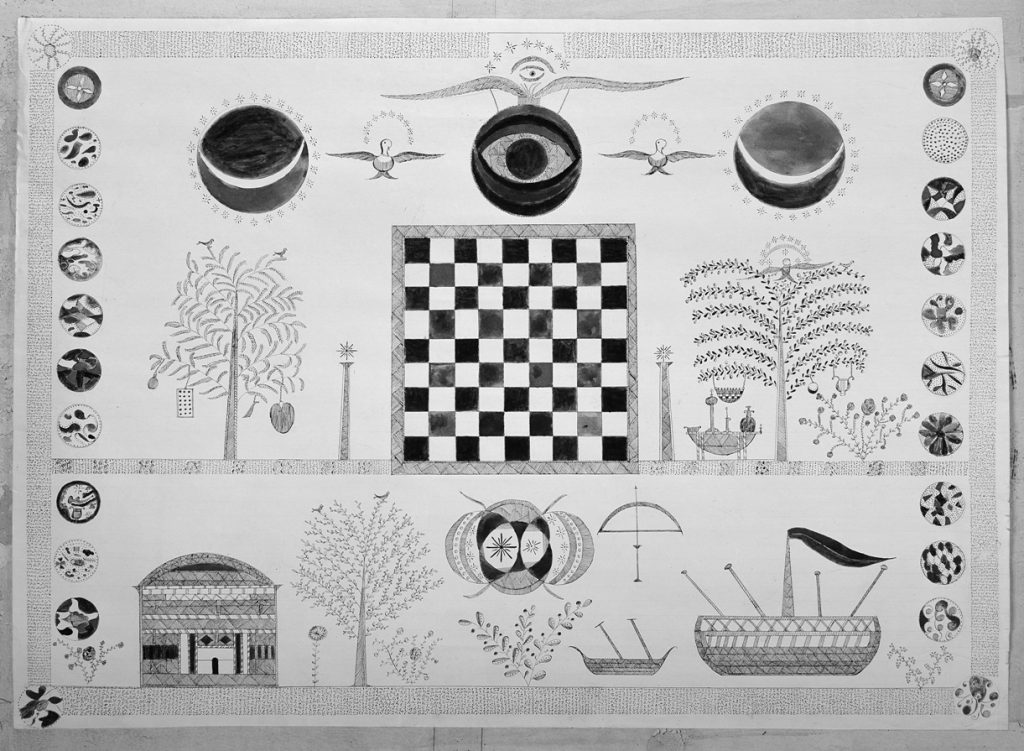

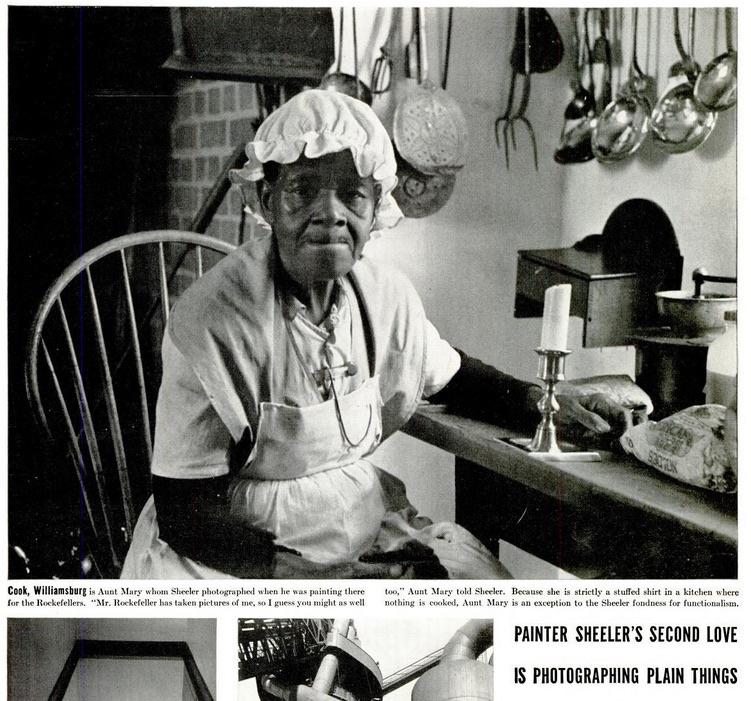

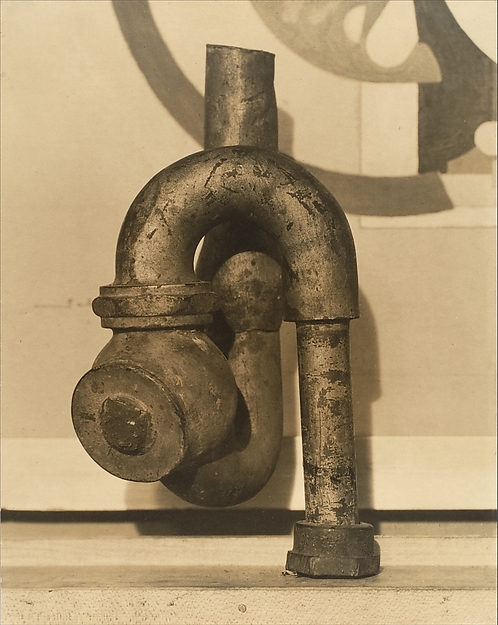

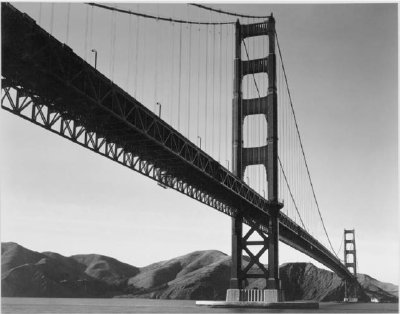

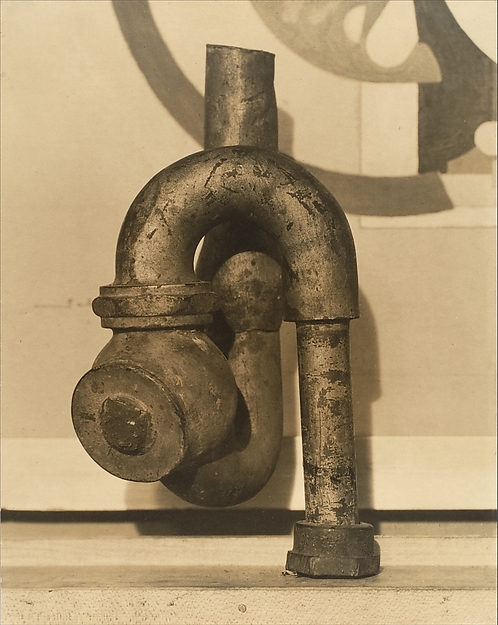

God, Elsa Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven, photo: Morton Schamberg, 1917, collection: metmuseum.org

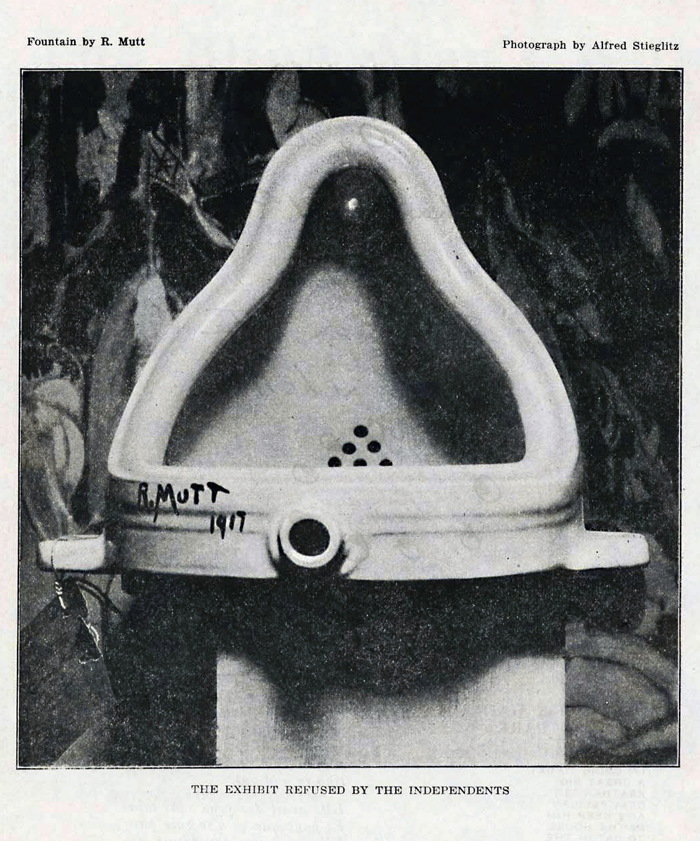

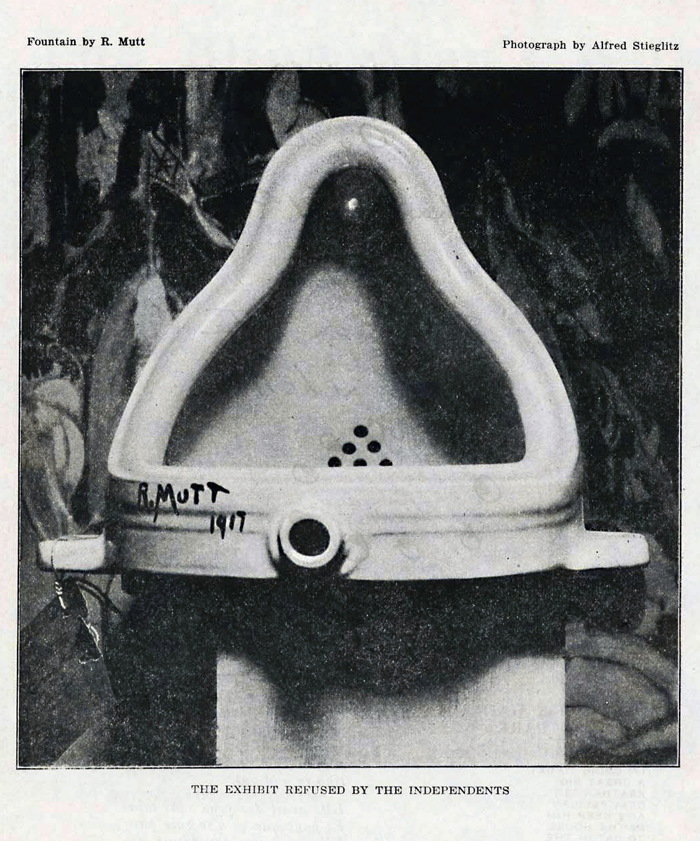

The claim that Duchamp “stole” Fountain from Elsa Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven was brought to the fore recently. The ostensible hook was a criticism of the reissue of Calvin Tomkins’ Duchamp bio, which doesn’t credit Freytag-Loringhoven. But authors Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson’s real goal is the delegitimization of Duchamp, and with him, the entire post-war art and theory that flowed out of Fountain. It’s the reactionary art historian’s equivalent of traveling back in time to kill teen Hitler. Here is Dr. Thompson trolling his commenters at The Art Newspaper:

Any of the global curatorial elite contemplating changing a label also have the problem of what to attach labels to, because the problem for a work art that draws its legitimacy from the acceptance by Duchamp of the attribution of Mutt’s urinal is that it is now required to obtain it’s legitimacy from somewhere else. Had Duchamp merely exhibited a urinal at the Janis Gallery in 1950 and explained it as homage to Elsa, whose urinal had been rejected by the Independents in 1917, there would be no problem, but there is, because the replica of 1950, attributed to Duchamp, and signed R Mutt, drew its authenticity from the attribution of Mutt’s original to Duchamp, a process which had begun with no complaints from Duchamp in 1935.The implications of this conundrum for the future of avant-garde art must now be addressed…

“Duchamp’s mean and meaningless urinal has acted as a canker in the heart of visual creativity,” they kicked, “Elsa’s puts visual insight back on to the throne of art,” as if they would for a minute support the artistic reign of Queen Elsa, whose outrages and transgressions troubled even the Dada-est of her contemporaries.

Fountain, 1917 assisted readymade by R. Mutt, apparently photographed by Alfred Stieglitz, as it was first seen and known via its publication in The Blind Man 2, May 1917

Which doesn’t mean they’re wrong. Their claims are not based on their own work, but on many years of carefully researched and argued publications of scholars like William Camfield, Irene Gammel, Amelia Jones, and Francis Naumann. Among the evidence: a letter Duchamp wrote to his sister in April 1917, just days after Fountain was rejected, attributing it to “one of my female friends,” which was only discovered and published in 1983. Also bolstering the case: the similarity of Fountain to God, top, Freytag-Loringhoven’s plumbing fixture-based sculpture of the same period. No brainer, right?

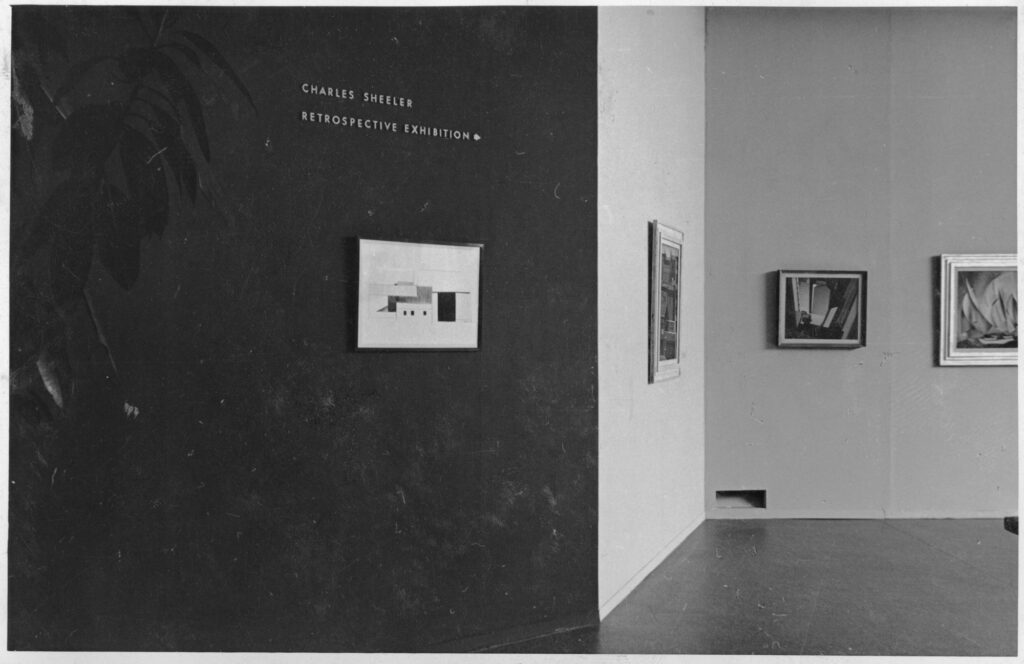

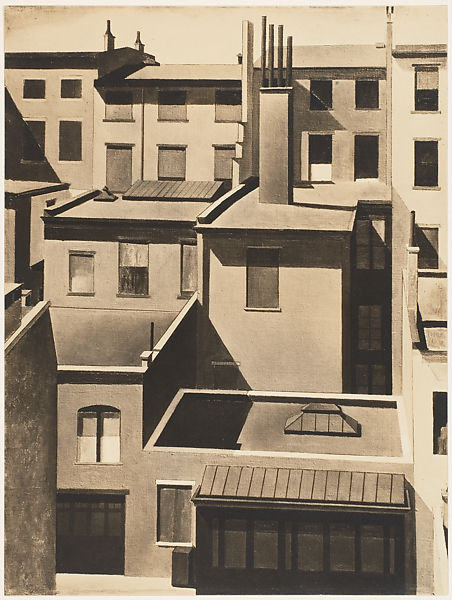

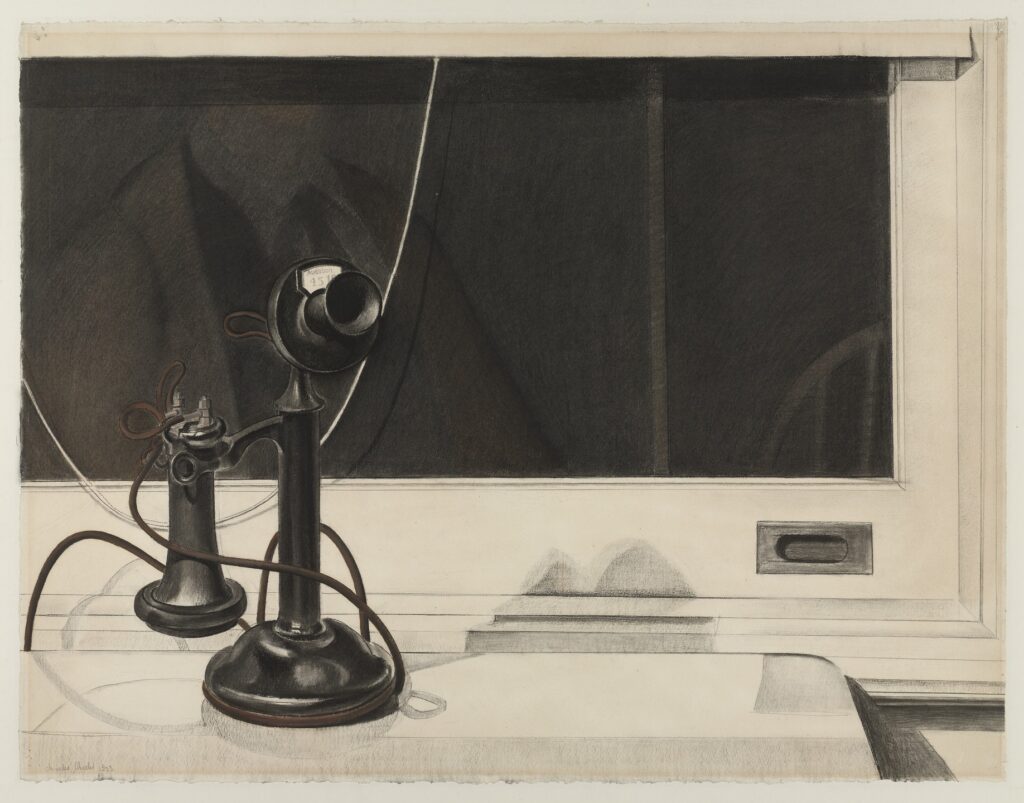

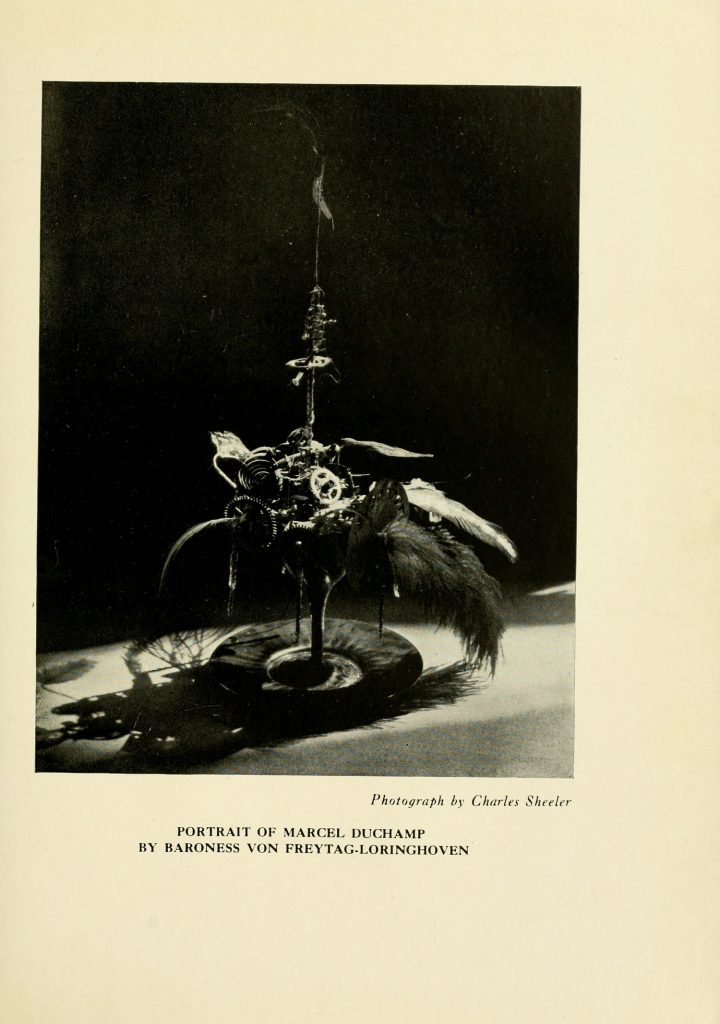

Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, c. 1920, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, photo: Charles Sheeler, via francisnaumann

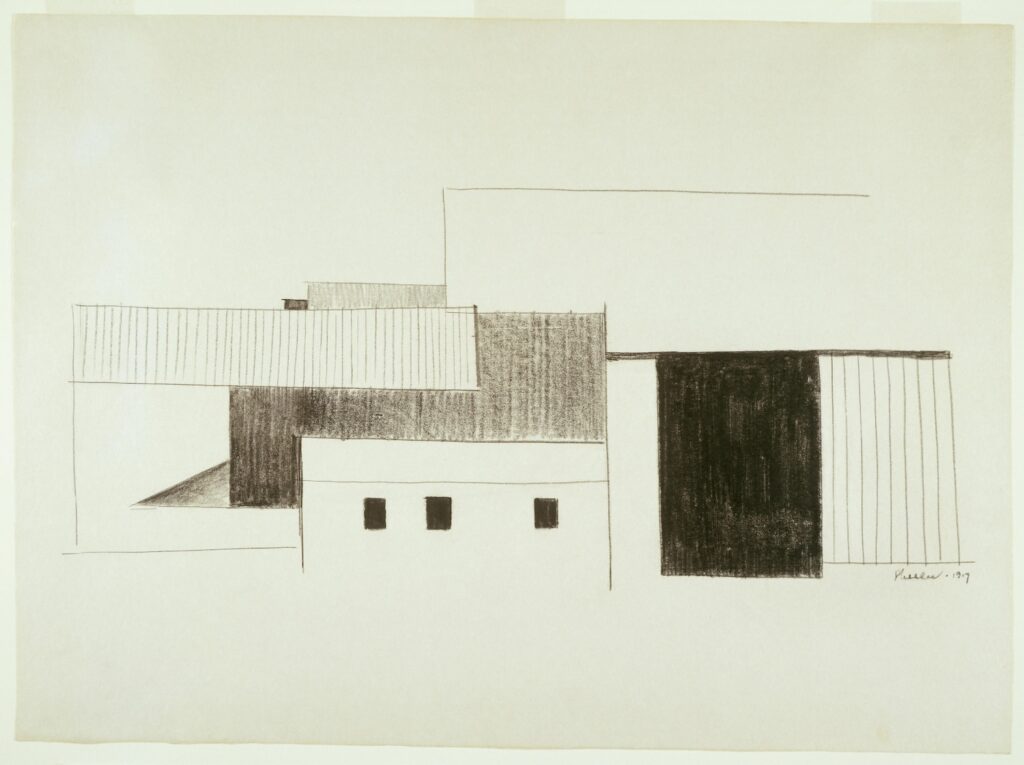

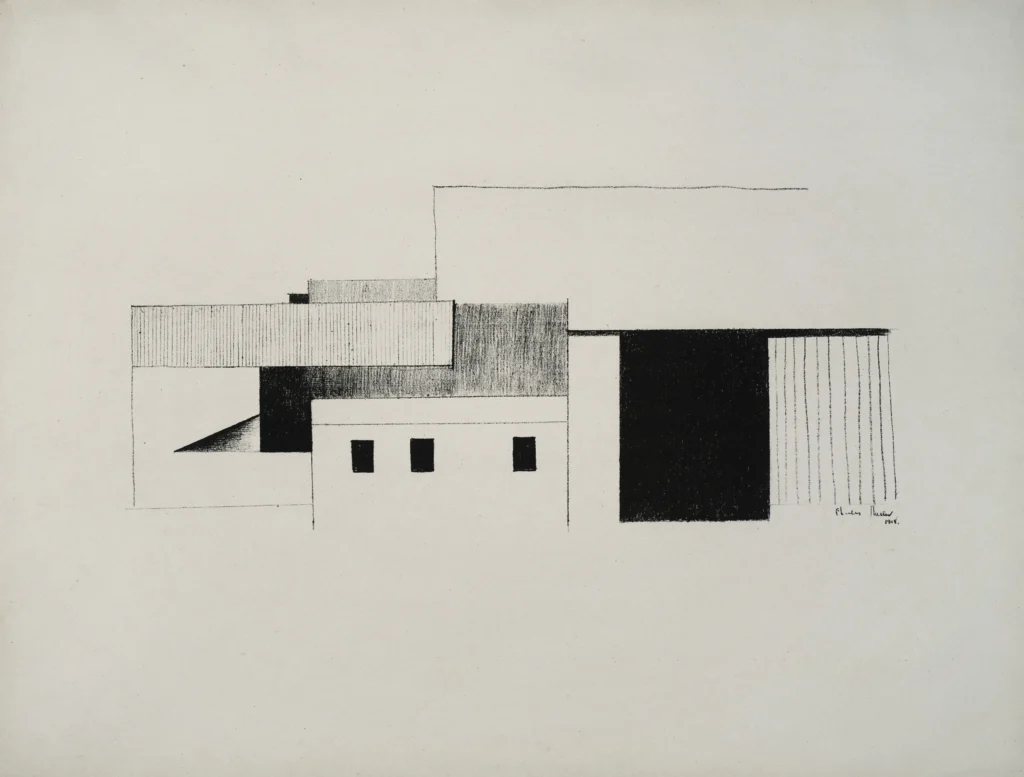

Except that for decades God was considered to be the work of Dada/precisionist painter Morton Schamberg. Schamberg was a close friend of decidedly un-Dada Charles Sheeler. Both Schamberg and Sheeler photographed artworks for money. Freytag-Loringhoven’s found object assemblage Portrait of Marcel Duchamp exists only in Sheeler’s photo of it, above, which was only discovered in the 1990s. They have separate billing. Naumann, who has written several of The Books On Duchamp, re-attributed God to Elsa in the mid-00’s, but so far she gets, at best, shared credit. One of the photos Schamberg took of God includes his own machine-inspired painting in the background, but two do not. This is the only sculpture associated with Schamberg, who died in the 1918 flu pandemic.

Morton Schamberg photo of God, image via christies

This Schamberg-less Schamberg photo of God sold at Christie’s in 2011. The estimate of $5-7,000 was in line with his market history; the result, $390,000, makes me think that the Baroness’s history was a factor and that someone out there believes in her God.

This God talk was weighing on my mind for a couple of months when I stumbled across a 200+ page oral history from UCLA of the pioneering West Coast abstractionist Lorser Feitelson, whose career began in New York in the 1910s and 20s:

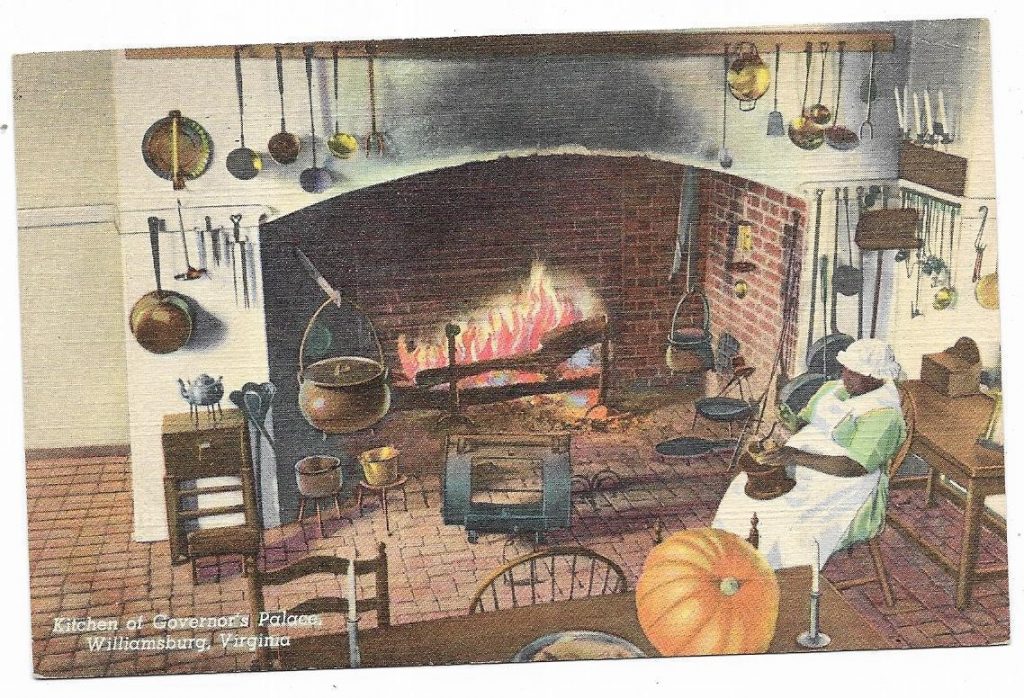

[Freytag-Loringhoven] would come up to visit us, …and she’d bring up all kinds of –I think I told you this–a cluster of pipes that she picked up right around the corner (they had razed one of those buildings), dragging this thing up the stairs. [It sounded like] somebody was busting the building. And she said, “Isn’t this a grand sculpture?” And she wasn’t kidding. Accident made this thing. What the hell difference does it make if the guy intended it or not? It wasn’t difficult to convince us.

The awesomely gossipy Feitelson tells the Baroness’s endless demands for sexual services from men and women alike, and of her many arrests for indecent exposure for “the way she dressed, in batik, with an opening there and dyed pubic hair, walking down Fifth Avenue.” And of how taking his young nieces to Elsa’s studio turned out to be “the worst mistake I ever made in my life,” when she identified the glittery pink nebula painting they were looking at as a belfie.

For all this, though, Feitelson’s most interesting story is of his first, daunting encounter with Freytag-Loringhoven, who picked up the young student at a live modeling session in Gertrude Whitney’s Studio Club and took him home.

Geez, I mean, what the hell kind of a gal is this? And here on the walls were shovels and all kinds of things. I said, “Marcel Duchamp.”* She said, “Yes, I know him very well.” I don’t mean to say that she took it from him–and I’m not sure. She was playing around with “found discoveries.” She would take the shovel and put it up against a background of some kind of a colored paper or materials. She had many such things, and they were wonderful.

God, cast iron plumbing trap on miter box, 1917, attr. to Schamberg & von Freytag-Loringhoven, collection: philamuseum

In a deal engineered by Duchamp, God was acquired in 1950, along with many major Duchamp works, by the Philadelphia Museum.. The Large Glass joined the museum two years later. God is currently credited to both Schamberg and Freytag-Loringhoven.

What if Elsa took the original In Advance of A Broken Arm? What if she helped make it? What if she and Duchamp conspired to create R. Mutt’s Fountain–which, remember, was identified almost immediately as a Buddha–and submit it to the Independents? Feitelson wrapped up his discussion of the Baroness with a segue to Duchamp: “[s]he had to have this terrific conceit and faith in her convictions. And I still say you cannot talk about Marcel Duchamp detached from other people.” In its own fitful way, the art world’s conversation is starting to shift.

* OK, I’ve wondered about this for a while, and now it’s a year later, and I am still wondering. I have a hard time figuring out how Feitelson would see a shovel hanging in a stranger’s studio and immediately associate it with Duchamp.

Feitelson actually said this drawing studio was before Whitney started her Studio Club, but that was 1914. And Duchamp only hung In Advance Of A Broken Arm in the studio he shared with Jean Crotti in November 1915. So no.

Feitelson said he was in NYC “during the war,” which would be 1918-19 from the US view of things. Whitney Studio Club was on W 4th St, and moved to W 8th in 1923. So that’s a possibility. But again, Duchamp had his shovel in his studio, and Feitelson never seems to have gone there. He never mentioned Crotti. He never mentioned the Arensbergs, the center of Duchamp’s circle, and exactly the kind of folks a namedropper like Feitelson would go on about. Did people talk about Duchamp’s studio objects? Because I don’t think he showed them publicly. Instead, I suspect this Elsa memory is a retrofit, Feitelson trying to make it sound like he knew what was going on in Elsa’s studio. There may have been a shovel, which would be interesting, very interesting! But I highly doubt if he saw it, Lorser Feitelson connected it at the time to Duchamp.