Painting is not photography, so the date of 1930-40 for a painting that includes a reference to a broadway show that only ran in 1925 is plausible, given other evidence. Merry Christmas and Happy Hannukah.

the making of, by greg allen

Painting is not photography, so the date of 1930-40 for a painting that includes a reference to a broadway show that only ran in 1925 is plausible, given other evidence. Merry Christmas and Happy Hannukah.

I’ve been trying and failing to make sense of this weird little Florine Stettheimer portrait of the art critic Henry McBride. It is one of two Stettheimers being sold this month at Christie’s by the heirs of Joseph Solomon, who executed Stettheimer and her sisters’ wills, and placed most of her artworks and papers in public collections. Except these two?

Continue reading “Henry McBride, Palm Treehugger”

I just read an excellent time capsule of an interview of director Todd Haynes by photographer Collier Schorr about his new movie Safe, which ran in the Summer 1995 issue of Artforum, almost midway between Safe’s debut at Sundance and its theatrical release in the fall.

Which turns out to be just one example of how time moved back then. The cover—for which there was no hook except art world vibes—was none other than Florine Stettheimer’s Studio Party (or Soirée). Don’t expect ME to demand an excuse to love Florine Stettheimer!

And then there were dueling reviews of a big Yves Klein retrospective, from Nan Rosenthal and Benjamin Buchloh, who—spoiler alert—may have disagreed on Klein, but they both disliked the show. And while neither of them answered the highly specific Yves Klein-related question that led me to this issue in the first place, I can’t complain.

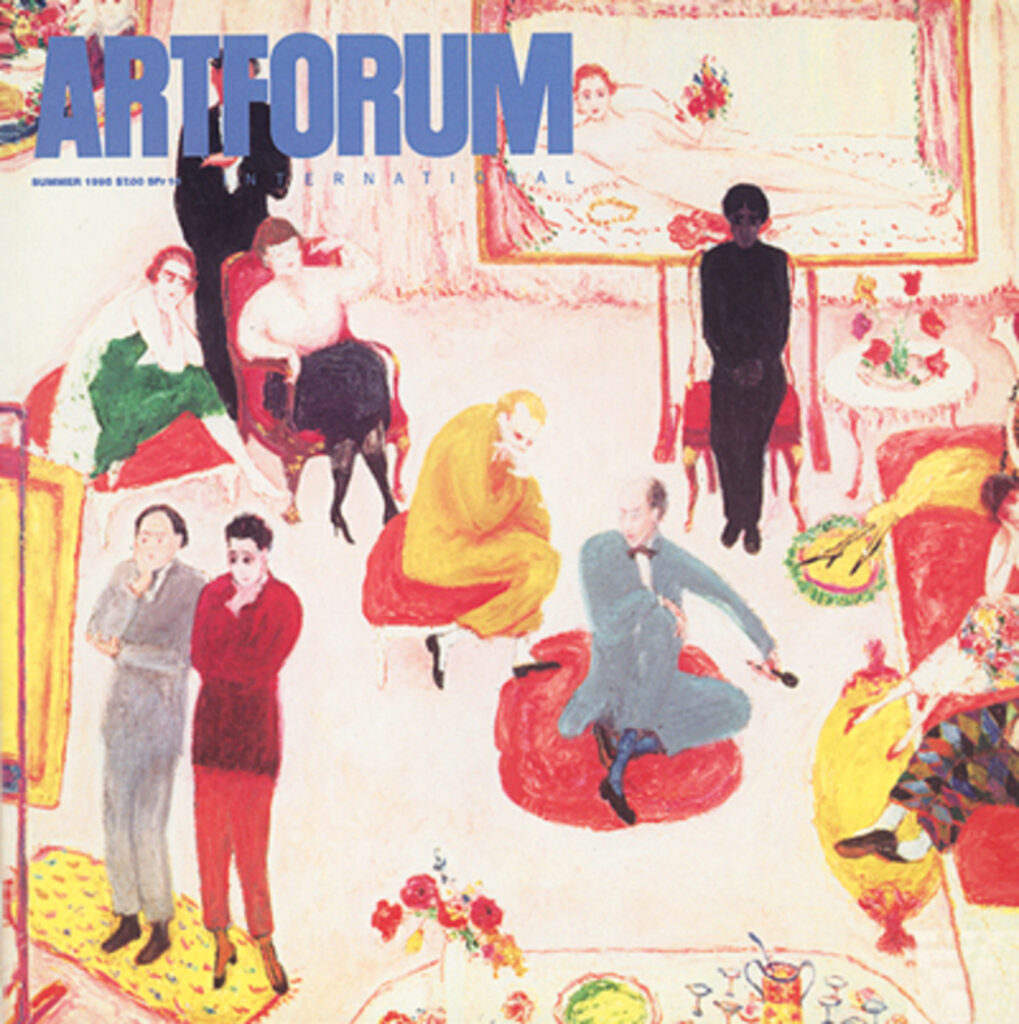

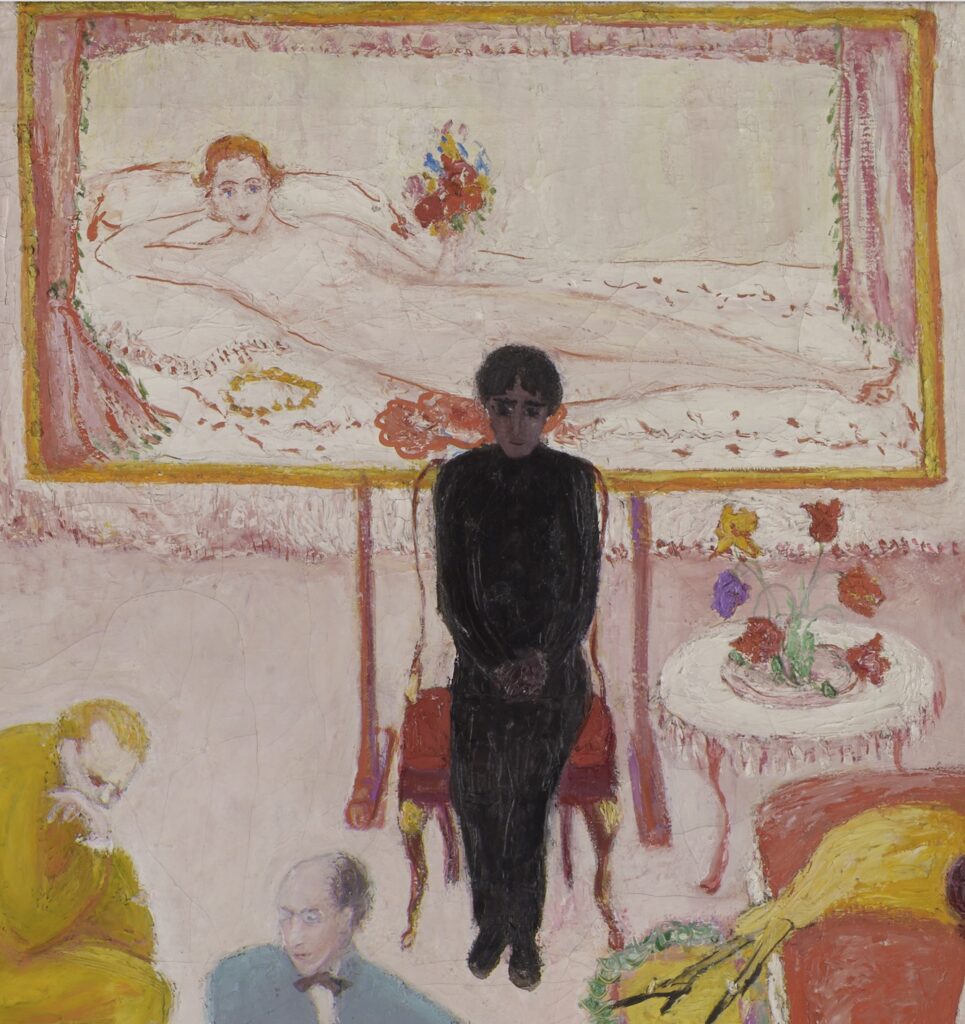

In her 1995 biography of Florine Stettheimer Barbara Bloemink identifies everyone the artist put in this painting of a painting unveiling, based on guests whose presence at such soirées had been recorded somewhere. I don’t have my copy of Bloemink’s book handy, but my guess is the sources were the correspondence and journals of Florine and Ettie Stettheimer at Yale’s Beinecke Library, which transferred the painting to the Art Gallery in 2019.

According to Bloemink, the two guys contemplating the painting in the lower left are sculptor Gaston Lachaise and cubist evangelist painter Albert Gleizes. Ettie Stettheimer is in green in the upper left, sitting next to poet Isabel Lachaise, the sculptor’s wife and muse. Painter/sculptor Maurice Sterne is standing behind them. Sterne’s wife Mabel Dodge, a friend of Gertrude and Leo Stein with a giant villa in Florence and a downtown Manhattan salon, who was part of the founding of artist colonies in Provincetown and Taos, is not pictured. But that’s Leo Stein on the pouf, next to playwright and Carl van Vechten squeeze Avery Hopwood on the ottoman. Florine Stettheimer herself is sitting on the sofa at right between Madame Juliette Gleizes and an unknown figure in harlequin pants.

Everyone’s accounted for so far, but Bloemink identified the dark-skinned figure in a black suit at the top center of the picture, sitting in front of the nude self-portrait Stettheimer never exhibited publicly in her lifetime—nor was it included in the posthumous show Marcel Duchamp organized for her at MoMA in 1946, although this painting was—as “Hindu poet Sankar.” Sankar, whose only mentions I can find are related to this painting, but it seems pretty clear the reason they were invited was to keep the painting from getting censored on Tumblr. So who even is Hindu poet Sankar, and what have they done? Literally every online mention of them tries to sound like of course, they know who Hindu poet Sankar is, but if you don’t know, they’re not going to tell you.

Anyway, Sankar looks a little uncomfortable, not to say out of place—no, stay right there, Sankar, don’t move, I’ll get you a drink. This is a family blog.

[At least it’s not just me update: In a 2017 paper [pdf] on the interrelation between Carrie Stettheimer’s well-known doll house models and, respectively, Ettie’s writing and Florine’s painting, Duke art historian Annabel Wharton notes that, even after enlisting the help of Asian Studies colleagues, she was unable to further identify “Hindu poet Sankar.” According to Wharton, Bloemink learned of the Sankar ID from a 1991 conversation with Yale’s longtime bibliographer and curator Donald Gallup [who died in 2000]. Gallup helped acquire and process Gertrude Stein’s papers, too, so he was familiar with the modernist milieu. Maybe the answer lies somewhere in the library.]

NEXT DAY UPDATE: With no information forthcoming from the Stettheimer side, it seemed useful to try looking around to see what prominent Indian poets or other figures were making the scene in New York City in 1916-1919. A couple of possibilities: In September 1916, a Columbia grad student named Shankar M. Pagar married fellow Columbia student Radhabai Pawar in what the Times called the first Hindu wedding on record in the United States. At least it was the first one in the Times. Their reception was at the Hindustan Association of America, an ex-pat student group where Pagar was an officer. There was no mention of poetry, though, and the Pagars were planning to return to India after completing their degrees in mid 1917.

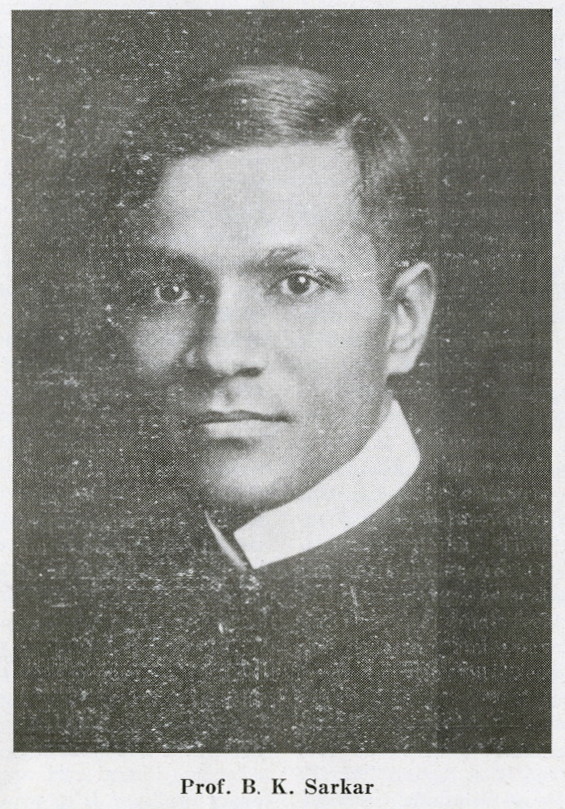

The HAA archives mentioned another, more prominent possibility: Benoy Kumar Sarkar, a prolific Calcutta sociologist and nationalist. I couldn’t find mention of Sarkar as a poet, or that he visited New York before the 1930s—and I gave up looking when his Wikipedia page said he praised Nazism and recommended India establish a fascist dictatorship [presumably a Hindu dictatorship instead of an English one.] But Twitter user @sand_fiddler pushed past that to find the Times ran a full-page feature & interview with Sarkar during a Spring 1917 US tour. Not only was Sarkar credited with publishing three volumes of Bengali poetry, his interview is laced through with references to Homer, Wagner, Chinese poetry, Walt Whitman, and Rabindranath Tagore. Now that we know he was in town, the only question remains the most salient one: is there any indication he visited Stettheimer? And that he might be the Sarkar/Sankar we’re looking for?

FEB 2024 UPDATE: Thanks to a comment from Tumblr scholar @Idroolinmysleep, published identification of Sarkar as Stettheimer’s “Sankar” now extends back 20 years. In 2012, NYU historian Manu Goswami identified Sarkar, and discussed his aesthetic theories and curatorial efforts in an extensive article on Sarkar and interwar internationalism. It’s a dense but fascinating read. Along with flagging a Sankar/Sarkar indexing error, Goswami cites a 2003-4 article on sculptor Gaston Lachaise by artist, art historian, and then-Met researcher Virginia Budny, that also identifies Sankar as “surely Sarkar.” Budny notes the same NYT article above, Bloemink’s date of the painting by a stretcher inscription [“August 25, 1919”], and Sarkar’s friendship with the artist Max Weber to put him in this NY artistic milieu. From here on out, any further mention of “Hindu poet Sankar” in discussion of Stettheimer’s work should be considered like brown M&Ms in Van Halen’s dressing room: a sign that the promoter didn’t read to the end—or dgaf if they got things right.

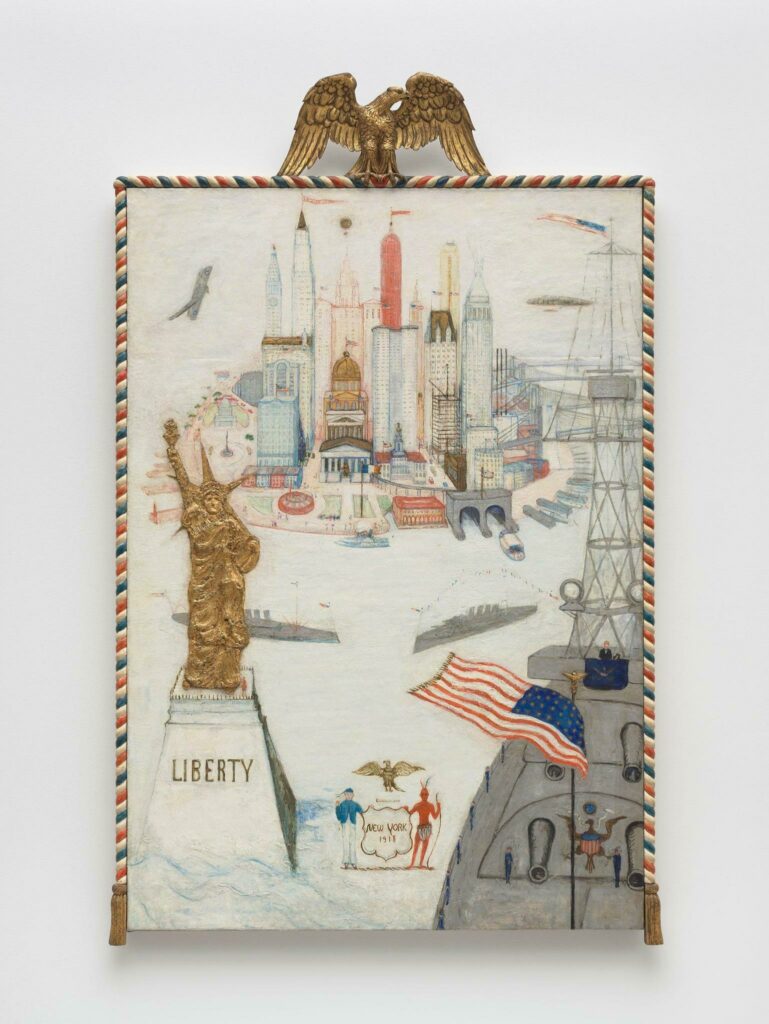

Writer and flaneur @CharlesFinch tweeted about seeing “this great and greatly weird” painting of New York, harbor, skyline and Statue of Liberty and all, at the Whitney Museum. Which is all the excuse I ever need to post about Stettheimer.

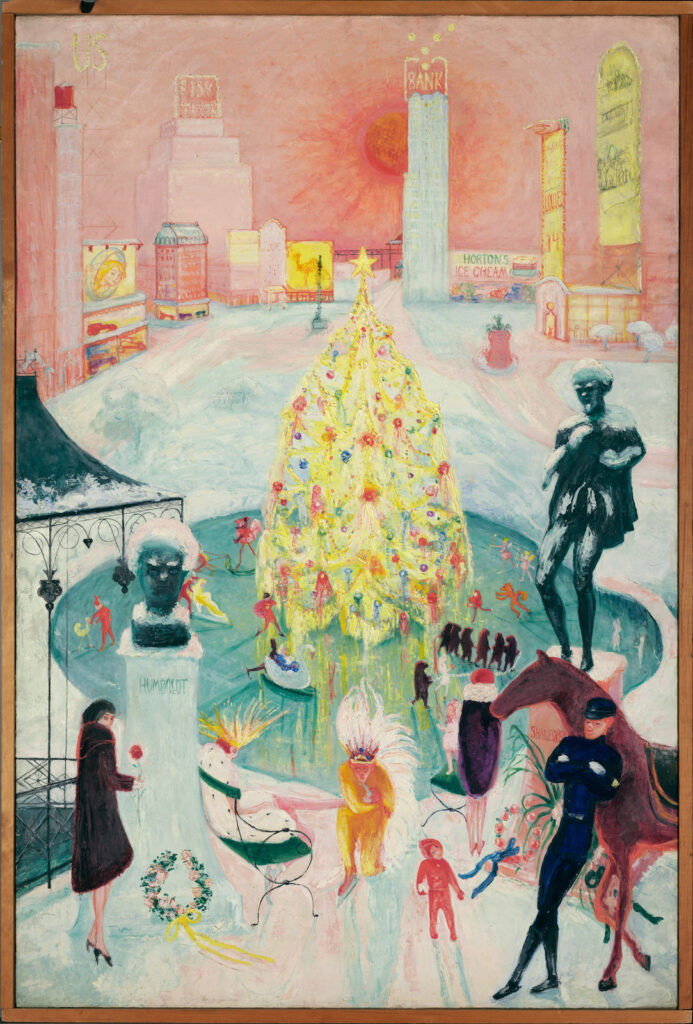

This particularly great one still sticks with me, too, from my first visit to the Gansevoort Whitney. As Andrew Russeth wrote at the time, they only actually acquired it in 2017. And it makes me think of another skyline Stettheimer painted a bit later, of the buildings of Columbus Circle circling a Christmas Tree in Central Park. That one’s at Yale.

New York – Liberty, 1918 [whitney.org]

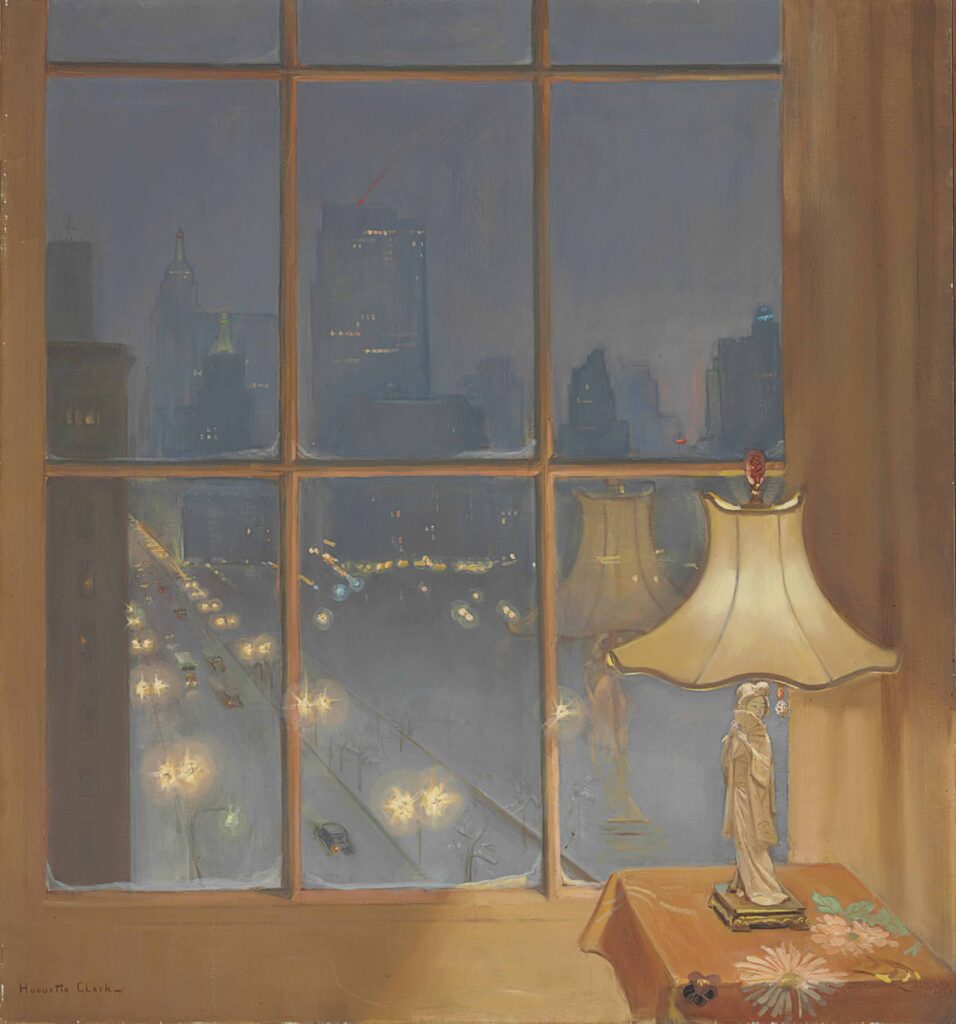

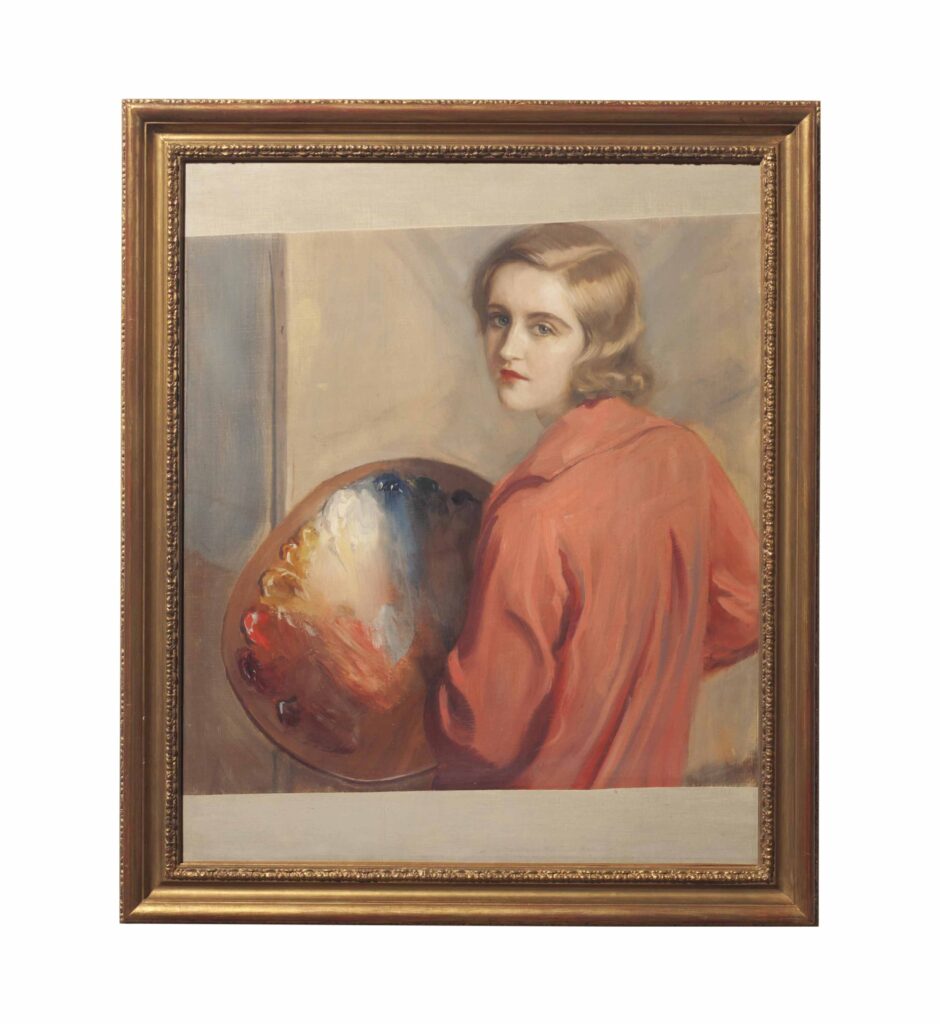

Wow, just when I thought we were having something very special when considering the implications of portraiture and erasure in a found real estate listing photo of a laundry dungeon in an epically gross American University flophouse–and I don’t mean to imply I’m not grateful for The Discourse–but anyway, y’all* were apparently also fine with letting me go yet another year without knowing that forgotten heiress recluse who kept up her sprawling Fifth Avenue co-op and Santa Barbara mansion like she’d be back any minute but actually checked herself and her doll collection into a midtown hospital room and only left decades later when she died in 2011 at 104 Huguette Clark made paintings?

And that except for a few included in a two-week show at the Corcoran Museum in Washington in Spring 1929–four years after her father’s death and the bequeathing to the Museum of 800 artworks and a Clark Wing–they were only first seen publicly in the jumble of an estate sale at Christie’s in 2014, where they sold for not that much money? Anyway, seventeen paintings by Clark were included in that sale, and she had some moments, mostly that window above, with the geisha lamp reflected in it. [Another four signed paintings, plus a couple of attributions, some prints, and an album of reproductions of her paintings, were auctioned in New Jersey in 2017, leftovers from Christie’s cataloguing. A highlight was this painting of a Dutch doll, which checks a lot of Clark boxes.

Also, though her teacher Tadeusz Styka specialized in painting portraits of socialite women, and once painted Clark appearing to paint a nude man, many of Clark’s surviving paintings are of Japanese women.

Continue reading “Huguette Clark Paintings??”

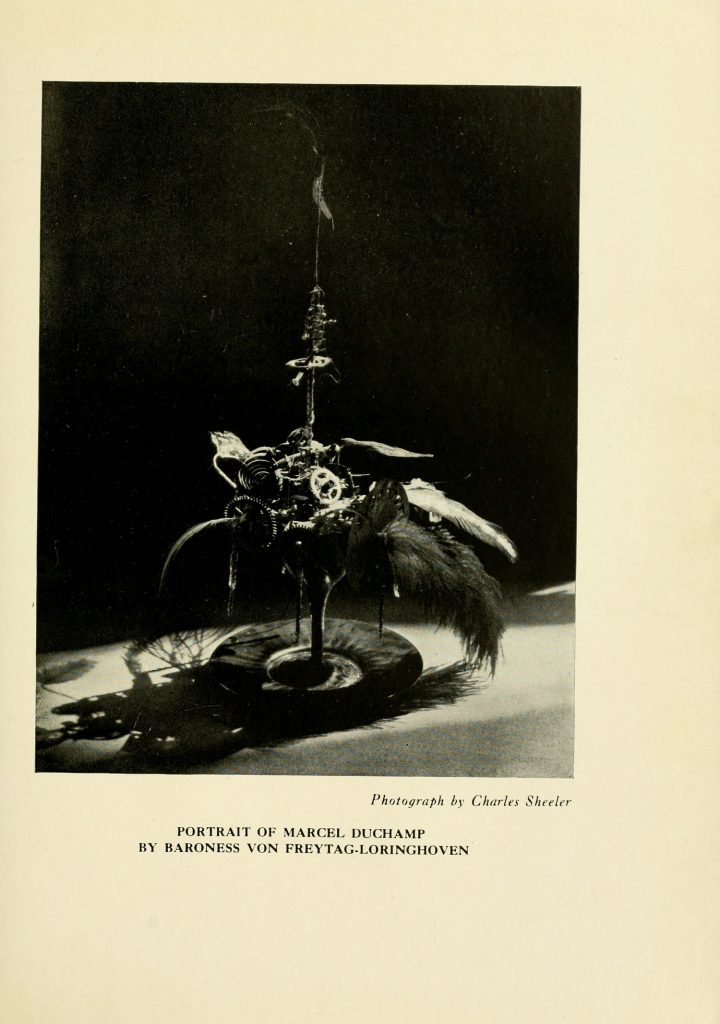

After 6 years and 72 issues, I am sure glad Margaret C. Anderson hung in there to publish one more issue of her avant-garde poetry magazine The Little Review in the Winter of 1922. Because it includes a different Charles Sheeler photo of Baroness Elsa’s Portrait of Marcel Duchamp.

The one that’s been floating around, via Duchamp dealer Frances Naumann, mostly, is a more clinical, perhaps Sheeler-esque photo [below].

The Baroness’s Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, ca. 1920

Gelatin silver print

9 5/8 x 7 5/8 inches, via francesnaumann

But besides the dramatic lighting, the Little Review version actually reveals more of the cocktail of feathers, gears, and flywheels that filled Baroness Elsa’s glass. Also it’s sitting on a plate.

All of this matters to me because this, my second favorite portrait of Duchamp after Florine Stettheimer’s, is lost, destroyed. And so this kind of documentation will help make a reconstitution of it truer to the original, and less of an inspired-by approximation.

Brown University and the University of Tulsa have digitized The Little Review as part of their Modernist Journals Project [brown.edu]

Previously, related Elsa-iana: In The Beginning