Where to even start? As a huge Charles Sheeler fan from early on, my first reaction was “GET IT.” This 1941 Sheeler photo is unusual so many ways. First off, the subject is a person, though one who is surrounded by the artifacts of early Americana that provided a grounding for the artist’s own modernist and precisionist leanings.

More on this person in a second, but second, this print was just deaccessioned by the Museum of Modern Art, and I missed the end of the Christie’s online auction because I was driving–and I forgot.

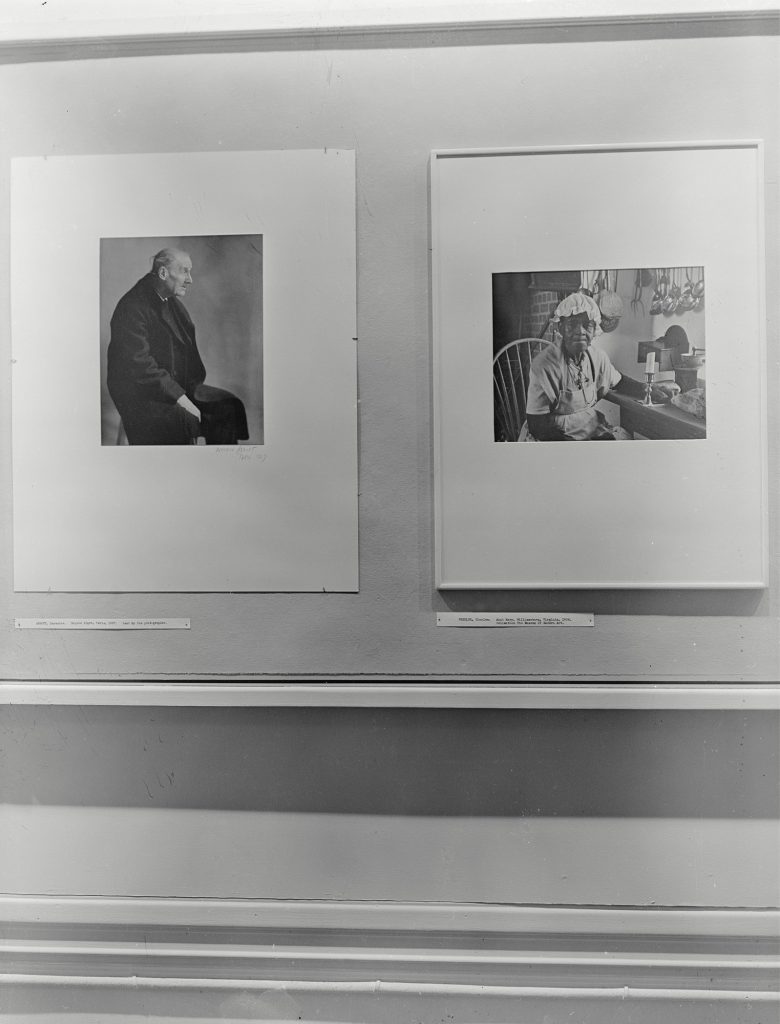

2.A? It was a new acquisition included in a 1943 exhibition of portrait photography. It hung next to Berenice Abbott’s portrait of Atget, which was a loan from the artist.

The print was a gift of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, the Modern’s co-founder. It is unsigned. The back has adhesive residue and an accession number. So I guess technically it might have been an exhibition print; back in the day, the connoisseurial taxonomies of photography were obviously less rigid, as were the accession guidelines of the Department, never mind there was a war on.

Anyway, such an illustrious provenance should smooth over any concerns. And yet the Christie’s estimate was only $5-7,000, a tiny fraction of a more typical Sheeler print. And the thing only got one bid, $1,500, and sold for just $1,875.

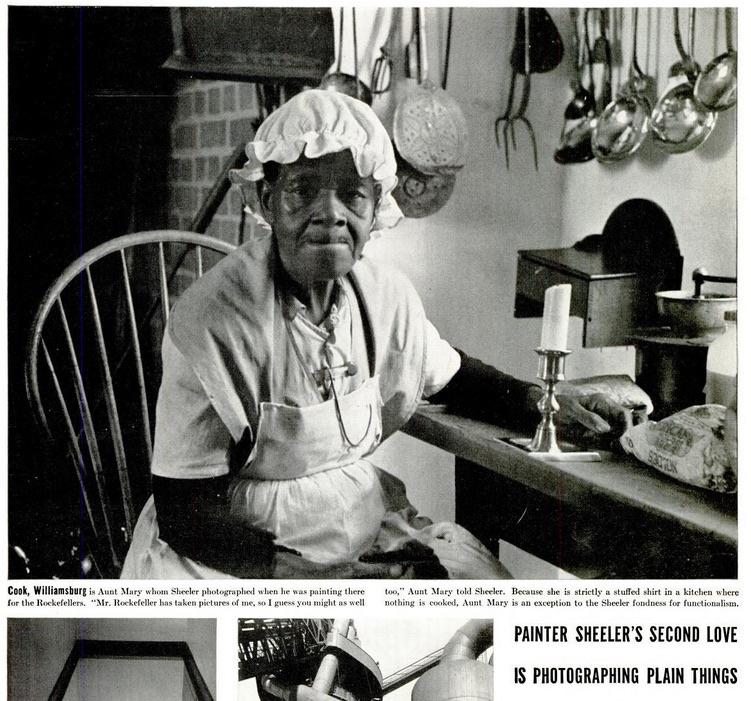

Maybe it’s time to go back to the first and most obviously striking thing about this portrait: the subject, an elderly African American woman with an apron, sitting in an antique kitchen, who, according to the photo’s title, is “Aunt Mary.” But whose Aunt Mary? Not the photographer’s, presumably, and not Abby Rockefeller’s, right? Well.

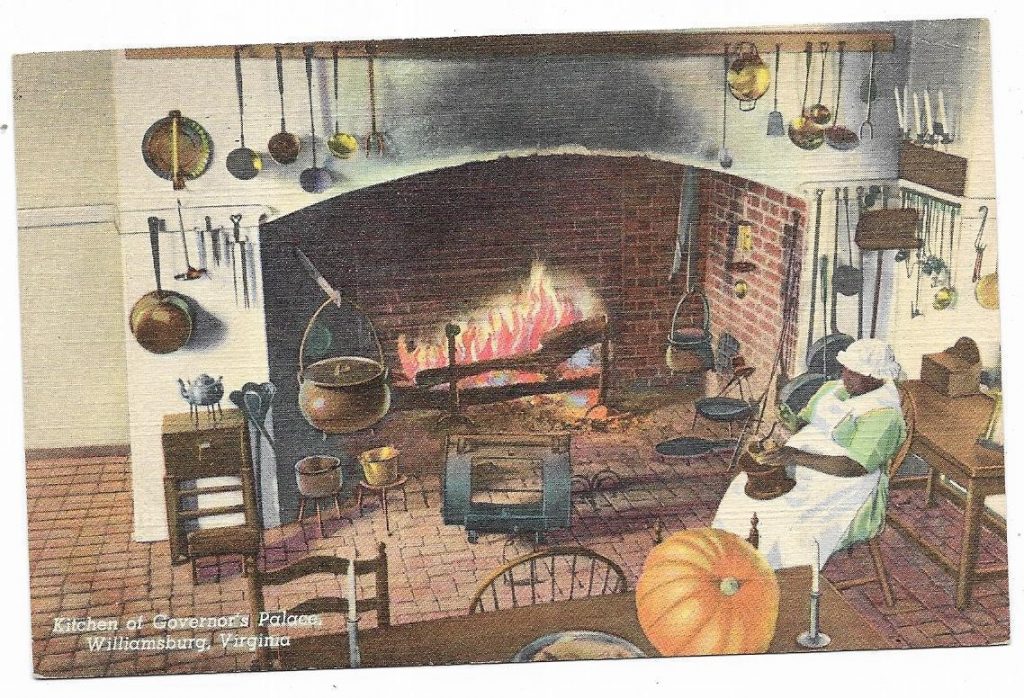

“Aunt Mary” turns out to be a character, a fictional enslaved worker in the kitchen of the Governor’s Palace at Colonial Williamsburg, another Rockefeller-founded culture venue that had just opened in 1934. On decades worth of Williamsburg postcards “Aunt Mary”, described as a “servant,” sits, head down, in a placid, domestic tableau.

To his credit, Sheeler photographed this unidentified performer as a person, not as a prop. Who was she? What was her job like? Assuming she’s from the area, southern Virginia, she looks too young to have been enslaved herself, but certainly old enough to be the child of former slaves. Until a push by activists and historians in the 1970s, “Aunt Mary” was one of the very few non-white historical characters in Williamsburg.

But why was Sheeler making it? I know and love his documentary photos from the Metropolitan Museum, but did he cover Williamsburg, too? Last year Kirsten Jensen curated a show of Sheeler’s fashion photography for the Michener Art Museum in Pennsylvania. What other Sheeler series and projects are lurking undiscovered in archives out there?

[2020 update:] While looking at some Met Museum Sheelers I’m reminded that Rockefeller was a supporter and collector of Sheeler’s art, and also invited him to photograph Colonial Williamsburg in 1935-36, thanks to Edith Halpert. So there are indeed more images out there, including Stairwell, Williamsburg, and whatever he used to make Kitchen, Williamsburg, duh.]

[2020 update again:] I just found this image was reproduced in a Life Magazine profile of Sheeler in 1938. The caption is pretty bad. This woman is identified as “Aunt Mary,” the enslaved character, even as she’s quoted–in Sheeler’s telling to the reporter–as the re-enactor she is: “Mr. Rockefeller has taken photos of me, so I guess you might as well, too.”

And then, “Because she is a stuffed shirt in a kitchen where nothing is cooked. Aunt Mary is an exception to the Sheeler fondness for functionalism.” Because LIFE does not understand the concept of performance, or a job, or a person, when that person is Black. Or maybe it’s Sheeler.