A couple of months ago while looking at those Danh Vo Japanese plate editions, I came across Blake Byrne, an LA collector who had sent one to auction.

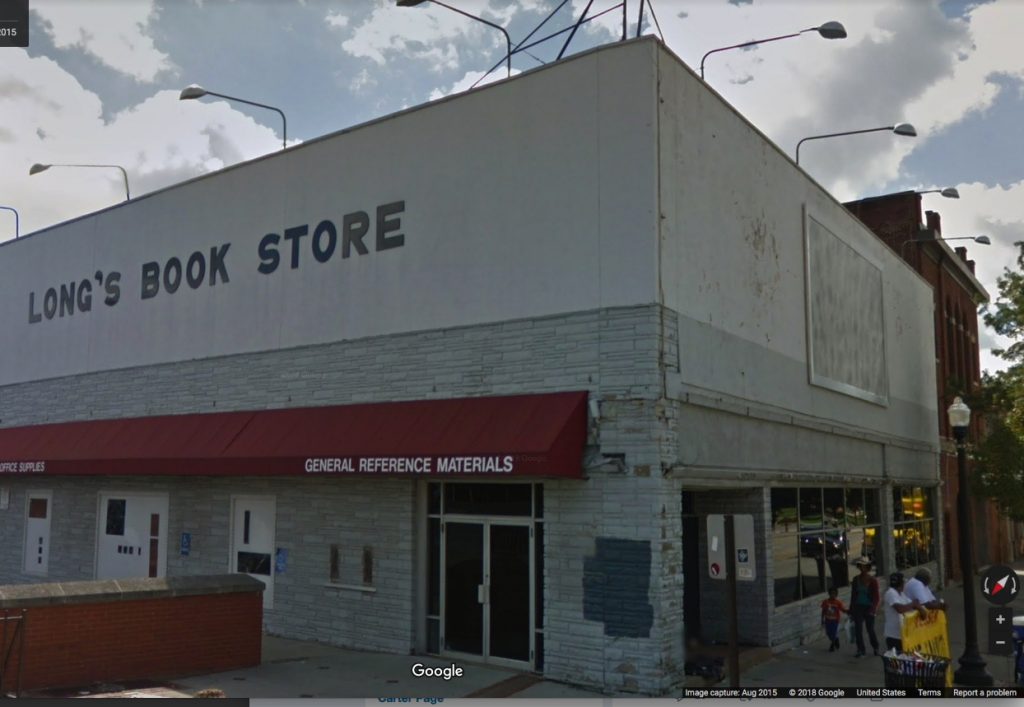

That led me to Open This End, a 2015 traveling exhibition from of works from Byrne’s collection, organized by various college museums and his Skylark Foundation. One stop was Ohio State University, which housed most of the show at the Urban Art Space, except for this: “Just off campus on the façade of the former Long’s Bookstore on the corner of 15th Ave and High St, is a work by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (For Parkett) (1994).”

Which made me wonder how that worked? Actually, I’d wondered for several years how Felix’s Parkett edition billboard worked in real life. It comes rolled up in eight big, silk screened panels, and once it’s installed in a site, that’s it; it’s permanent. So far, my attempt, begun in 2012, to document all 84+15AP editions had gone nowhere. But now I had a new datapoint. Maybe. How does a one-and-done billboard in a traveling show from a private collection work?

Sure enough, here it is on Google Street View in 2015, facing the OSU campus entrance right by the Wexner Art Center. Let’s scrub forward to see how it has held up?

Oh.

I emailed Skylark Foundation executive director Barbara Schwan to find out what happened. She looped in Joseph Wolin, curator of Open This End, to explain. After much consultation with the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation and Parkett, Byrne donated his edition of the billboard to OSU, where it was installed for several months on a building that was slated for demolition.

When the building came down, the billboard came down with it. Wolin wrote:

We were told, I forget if it was by Parkett or the Foundation, that this was one of the very few times, if not the only time, the billboard had been installed as a billboard, so we were pretty excited about that. Blake himself had acquired the work at auction and had it rolled up in storage for many years, so for me it felt rather wonderful, if bittersweet, to be able to realize it as the artist had intended. Apparently, when the work is installed indoors, as in Parkett’s exhibitions, the panels are often just pinned to the wall and rolled up again after.

So many questions answered, so many questions raised. Six years ago I lamented that “Untitled” (for Parkett) is “doomed by its own nature to exist in a state of fungible incompleteness, or worthless realization, or inevitable destruction.”

Which, thanks to a generous donation and successful realization with full knowledge of its destruction, we realize is a feature, not a bug. I hope more owners of “Untitled” (for Parkett) follow Byrne’s lead by realizing their billboards and letting time take its toll in public rather than in storage. It is what Felix would have wanted.

Previously, related:

You Don’t Complete Me, Or Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled” (for Parkett), Part 1

Infiltration & Replication, “Untitled” (for Parkett), Part 2