New York, montage photomural, Berenice Abbott, all images via moma’s 1932 catalogue

I’ve been meaning to post this for a couple of months, but with museum censorship battles and political mural controversies in the news, what better time, right?

When I started researching the history of photomurals–or more precisely, the photomurals of history, since I was mostly just posting various photomurals I’d discovered–I was interested in their context, in the exhibitions and expos they were created for, and whether they were considered or treated as art.

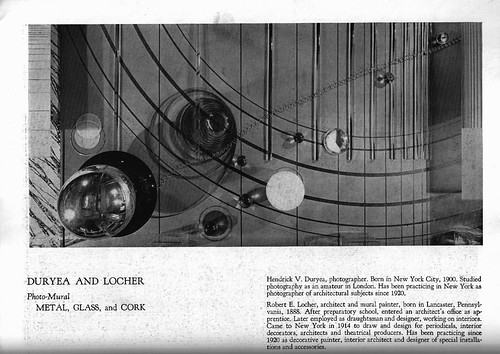

Metal, Glass and Cork, Hendrick Duryea and Robert Locher

Painted murals had a long, deep history as an accepted art form, but photomurals were marginalized twice, as photos, and as murals. They seemed to occupy some indeterminate space between art and architecture, art and journalism, art and educational/exhibition tool, art and propaganda, art and decoration, art and design.

So at first I was stoked to find what may be the ur-photomural show–at The Museum of Modern Art. Only after looking into it do I find out what a chaotic, politicized, controversial disaster the show turned out to be.

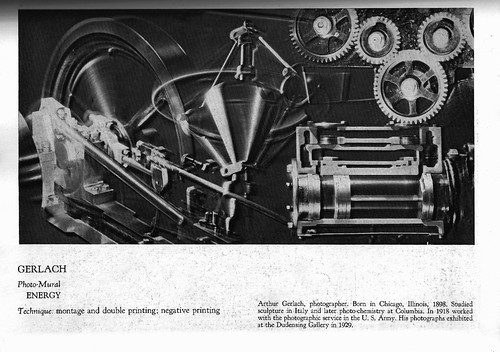

Energy, Arthur Gerlach

In May 1932, Lincoln Kirstein organized “Murals by American Painters and Photographers,” the first temporary exhibition in MoMA’s new standalone building on 53rd Street, and the first to include photography.

He originally conceived the show as a promotional tool, but for murals themselves. Citing recent “Mexican achievement” in the field, Kirstein argued for the modern mural’s compatibility with modern architecture:

While the Exhibition will interest the general public, it is hoped that architects and others responsible for the selection of mural designers will study these paintings and photographs with special reference to the possibilities of beautifying future American buildings through the greater use of mural decoration.

65 invited artists ended up submitting 35 painting and 12 photo murals on the subject of “The Post-War World.” Painters were asked to submit a 2×4-ft study, plus one 4×7-ft high panel. The photomurals were to fit a 7×12 ft wall.

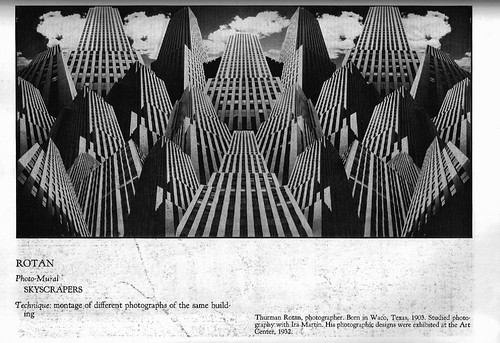

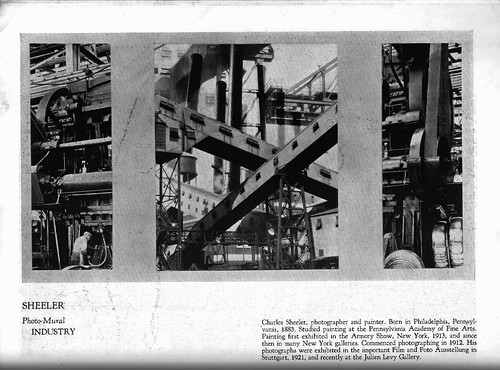

I couldn’t find much beyond the participation of Sheeler and Stieglitz, so I finally ended up tracking down the catalogue and scanning in all the works in the photomural section. [The show included: Berenice Abbott; Maurice Bratter; Hendrick Duryea and Robert Locher; Arthur Gerlach; Emma H. Little and Joella Levy; George Platt Lynes; William Rittase; Thurman Rotan; Charles Sheeler; Stella Simon; Edward Steichen; and Luke Swank.]

I think they look kind of fantastic. Overall, the photomurals–curated for Kirstein by dealer Julien Levy–were far more interesting, modernist, and innovative than the largely figurative…muralistic paintings.

Maybe the fact that none of these works survive, and that the post offices and public buildings of the New Deal era are not, in fact, bursting with rich, semi-abstract, chiaroscuro photomurals celebrating American industry and technology, just means that the show was ahead of its time.

Skyscrapers, Thurman Rotan

I didn’t know Thurman Rotan’s name before, but I recognized his awesome Skyscrapers montage.

Industry, Charles Sheeler

I’ve been a longtime Sheeler fan, so the idea of a wall-sized Sheeler River Rouge photo is very enticing. This was refabricated at least once for an exhibition, but otherwise, only a small set of prints from the show exists.

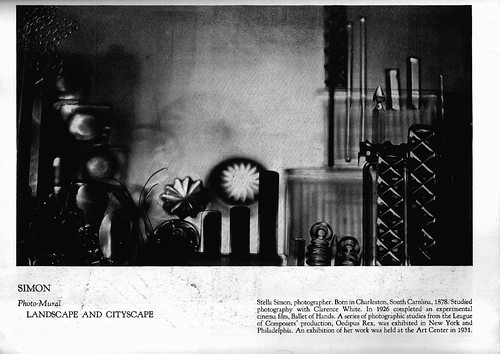

Landscape and Cityscape, Stella Simon

I love this, Stella Simon, whoever you turned out to be. In his amusing essay, Levy warned photographers that just blowing up a regular photo to wall-size wouldn’t work. Simon obviously had a grasp of scale.

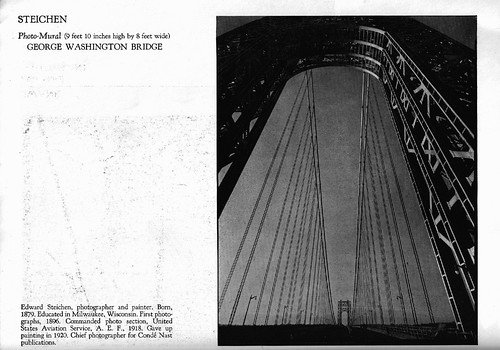

George Washington Bridge, Edward Steichen

Steichen, meanwhile, probably DID just blow up his photo. Instead of complying with the show’s 7×12 format, his mural was 8×10 feet. Still, I think it works.

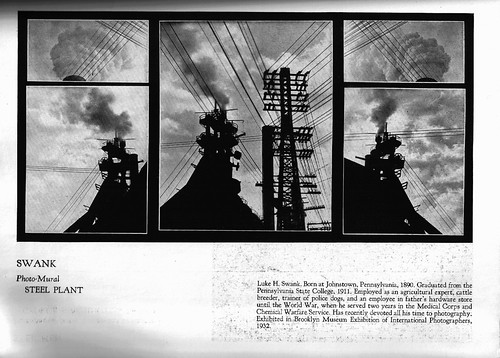

Steel Plant, Luke Swank

Besides being full of women [well, 4], interesting work, and artists I’d never heard of, the photomural section also introduced me to the work of the awesomely fake-sounding Luke Swank.

The only work that’s missing is one I really wanted to see: News, “a montage of photographs used for Rotogravure Section of New York Times, was submitted by the pioneering Times photo editor Emma Little and Joella Levy, the young wife of the curator.

From all the dealer/curator/photographer coziness and the show’s explicit mission to sell murals to the builders of Rockefeller Center and beyond, you’d think that would be the source of the show’s conflict. But no, it was The Reds, communism.

As Martin Duberman recounts in his excellent biography of Kirstein, several murals had communist or anti-capitalist-related themes that infuriated several trustees. The Museum’s president, A. Conger Goodyear demanded the “offensive” works be removed, or that the show be canceled entirely. The titles alone give you a hint of the contended works: Last Defenses of Capitalism by Hugo Gellert; Class Struggle in America Since the War by William Gropper; and The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti by Ben Shahn.

Fortunately, ArtNews published an excerpt from Duberman’s book about the battle, which includes Alfred Barr decrying the “threat” of an artists’ boycott, and Kirstein’s alternately manic and deft maneuvering alongside his young ally and champion–whose mother had founded the Museum–Nelson Rockefeller. Kirstein prevailed, though several trustees–but not Goodyear–did resign.

Shahn’s mural panel was later acquired by the Whitney. In 1967, Syracuse University invited Shahn to create a mural, and he opted to finally realize his original 1932 design.

scans of all 11 photomurals from the 1932 catalogue of Kirstein’s MoMA show [flickr]

Seeing Red At MoMA [artnews.com]

Buy Maritin Duberman’s The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein [amazon]