Cy Dear was a saddening revelation. The 2018 documentary by Andrea Bettinetti tells a story of Cy Twombly’s life, but its subject is actually Nicola Del Roscio, Twombly’s longtime partner who has spent his life enabling the artist’s work, and managing his legacy. In the process Del Roscio’s own sadness and grief seem to have gone untended, and now loom over the landscape he’s so fastidiously cultivated. I’ll need more time to process Cy Dear and the implications of Twombly’s life on his work and the people around him.

But one thing that finally makes some sense is Twombly’s photographs. Not how their copyrights have all been assigned to the Nicola Del Roscio Foundation. That always struck me as a natural gesture: the Polaroids Twombly made throughout his decades of days were left to the person he spent all those days with. What I could never figure out is what they were, and how he made them.

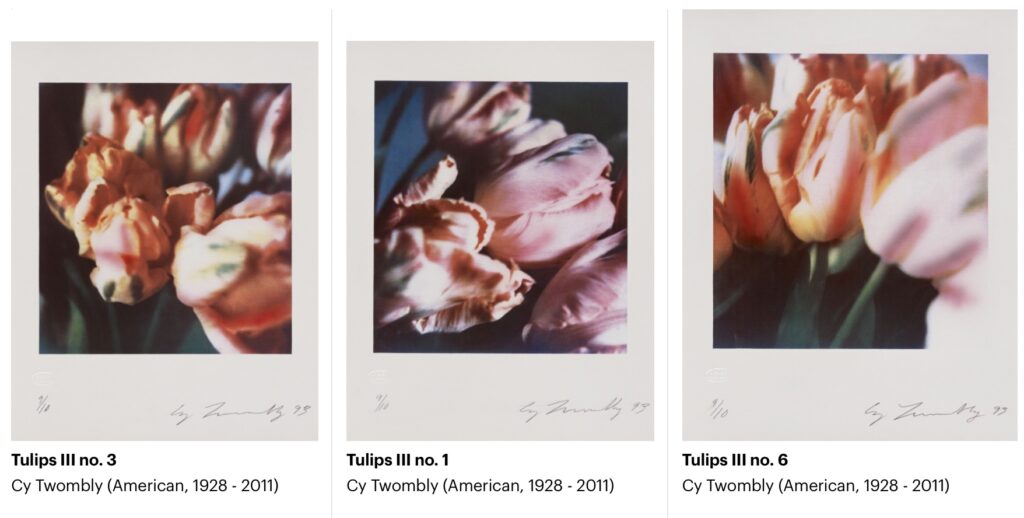

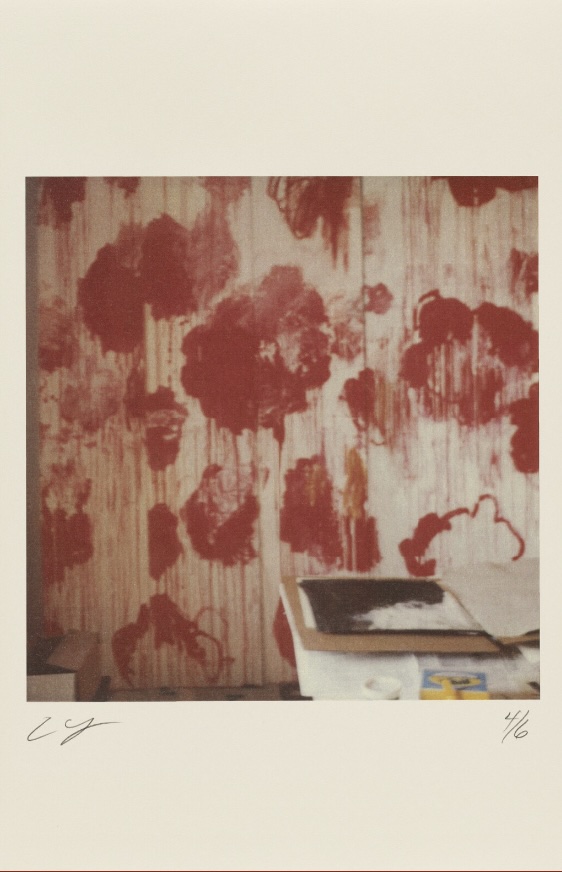

Cy Twombly made photographs in two eras: with Rauschenberg in the early 1950s, and from the mid-1970s onward, when he got a Polaroid instant camera. From that point on he took pictures all the time until he died, it seems. When earlier pictures began to degrade, at least by the early 1990s, he had some rephotographed.

He did not show photographs, though, until 1993, at Matthew Marks. I remember this, and it was an unusual deal. I also remember MoMA not including any photos in Twombly’s retrospective the next year. So officially, they were kept to the side of his project.

Those photos were grainy and lush and felt very 80s. It turns out they were produced beginning in 1991 using the almost ludicrously laborious Fresson Technique, a century-old, hand-coated, pigment-based, color-separation process kept alive by one secretive family in France. This phase did not last.

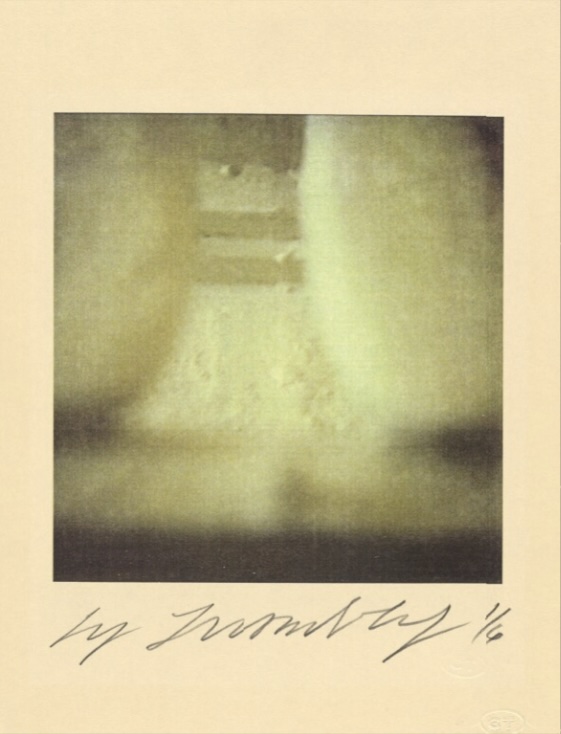

From 1995 through 2000, Twombly made what he called “dry-prints,” which have to be the diametric opposite of the wet & sloppy Fresson prints. Except no one really has paid much attention to the details. Some writers just conflate the two processes. But “dry-prints” are called “electrophotography” by the institutions that collect them, but the are better known as “color photocopies.” Cy Twombly printed his photos by enlarging his Polaroids on a color copy machine.

As Wayne Bremser—who first told me Cy Dear is streaming on Kanopy—noted, the “dryprints are color copies” thing was mentioned 13 years ago. But since Twombly’s photos are mostly encountered in reproduction in books, no one notices or cares.

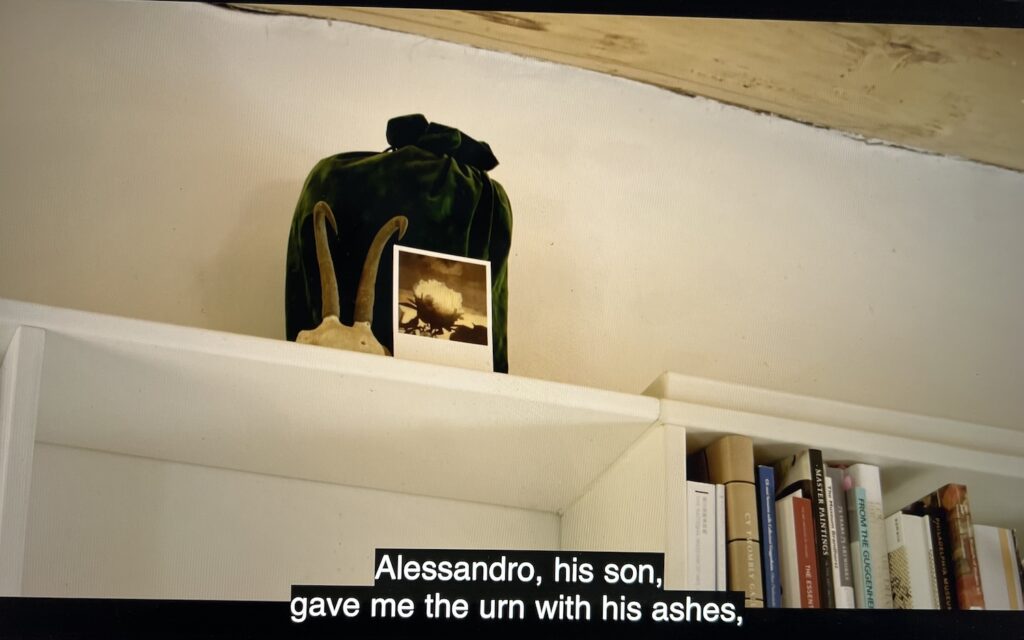

And here’s where Cy Dear delivers the info. As these two quotes from Del Roscio and longtime Twombly publisher Lothar Schirmer reveal, there was a Kinko’s in Lexington, followed by a hunt in Munich:

Nicola Del Roscio: in the later years he dedicated himself more and more to photography. It was something he liked because it was less exhausting for his old age. He used Polaroids for their immediacy. Then he was re-elaborating them on a photocopy machine we found in a shop in Lexington. Unfortunately the shop eventually closed down, and Cy stopped printing pictures there.

Lothar Schirmer: They were very beautiful, blurry and “unsharp” kind of pictorialism. Every time I phoned or was in touch, I heard complaints that he couldn’t print his photographs any longer.

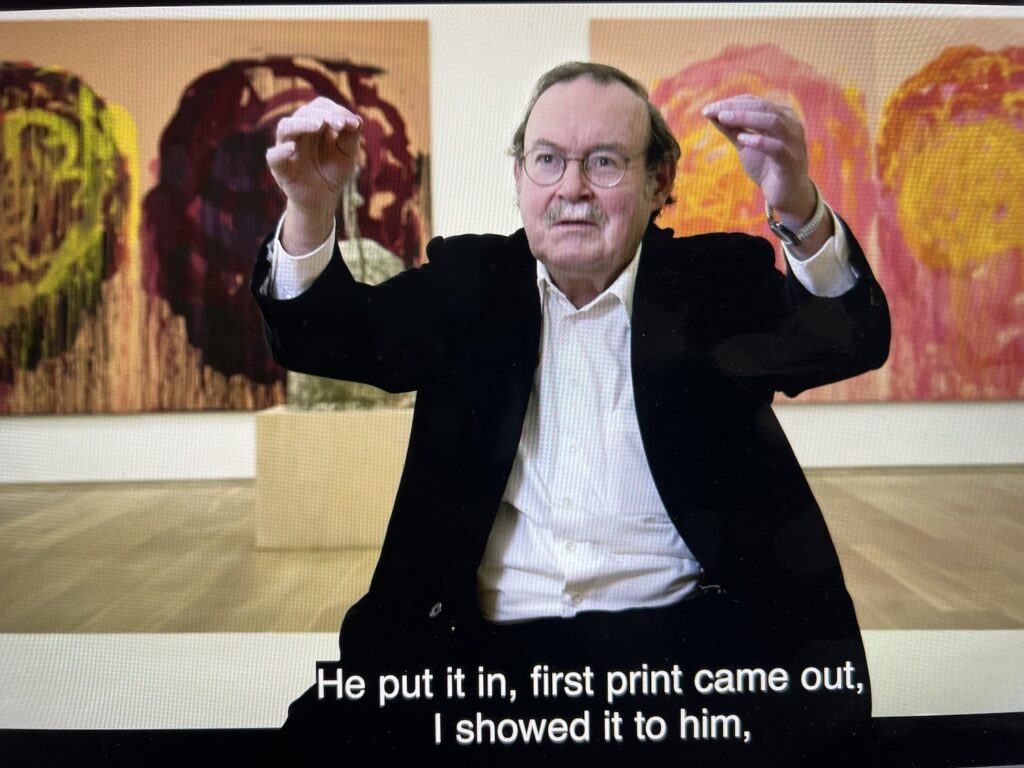

One day, after four years, I sent my assistant to all the Munich copy shops. After two days, he came and said, “I have a machine which is very similar.” Next day, Eleven o’clock: “Lothar, you found the machine! I’m coming! I’m coming!”

He had a bag and a carton—a shoe carton—filled with Polaroids, and he was sitting in our office at a desk, and was like a card player, making piles. And then he took one and said: “Try this.”

He put it in, first print came out, and I showed it to him. He said, “Maybe a bit more red.” OK, a bit more red.” [pantomimes changing the machine settings]. Next print: “Maybe a bit more black.” Then third trial, and then: “Perfect! go for it!”

We worked all day long and at the end, it was sixty motifs, or seventy. And the next day it went on, and suddenly in Munich the rumor was spreading, that Lothar Schirmer had a money-printing machine! [laughs]

The third, Munich Phase which began “after four years,” then, is 2005. It seems to extend past the artist’s death in 2012. Many Lexington photos are 11 x 8.5 inches. Many Munich photos are 17 x 11 inches. They’re on “cardboard,” which I think means cardstock? I have not handled a dryprint.

In 2015 The Getty acquired 29 Twombly photos of all three phases, and their collection database helpfully includes where a work was made. This maps now to the Cy Dear retelling.

As an aesthetic, it makes perfect sense, this whipping between the laborious antique handmade and the instant pushbutton technological. While his friend Sally Mann is developing glass-plate negatives of southern swamps in her trunk, Twombly was dragging Larry G on tours of the Walmart two towns over. I can’t tell if it’s too bad Twombly didn’t make it to the Instagram filter era, or for the best. Collector-wise, is it just misguided fetishism to want the high-craft, archival prints over some fugitive sheet-fed product? After all this, maybe the best format for experiencing Twombly’s photos is to buy the book.