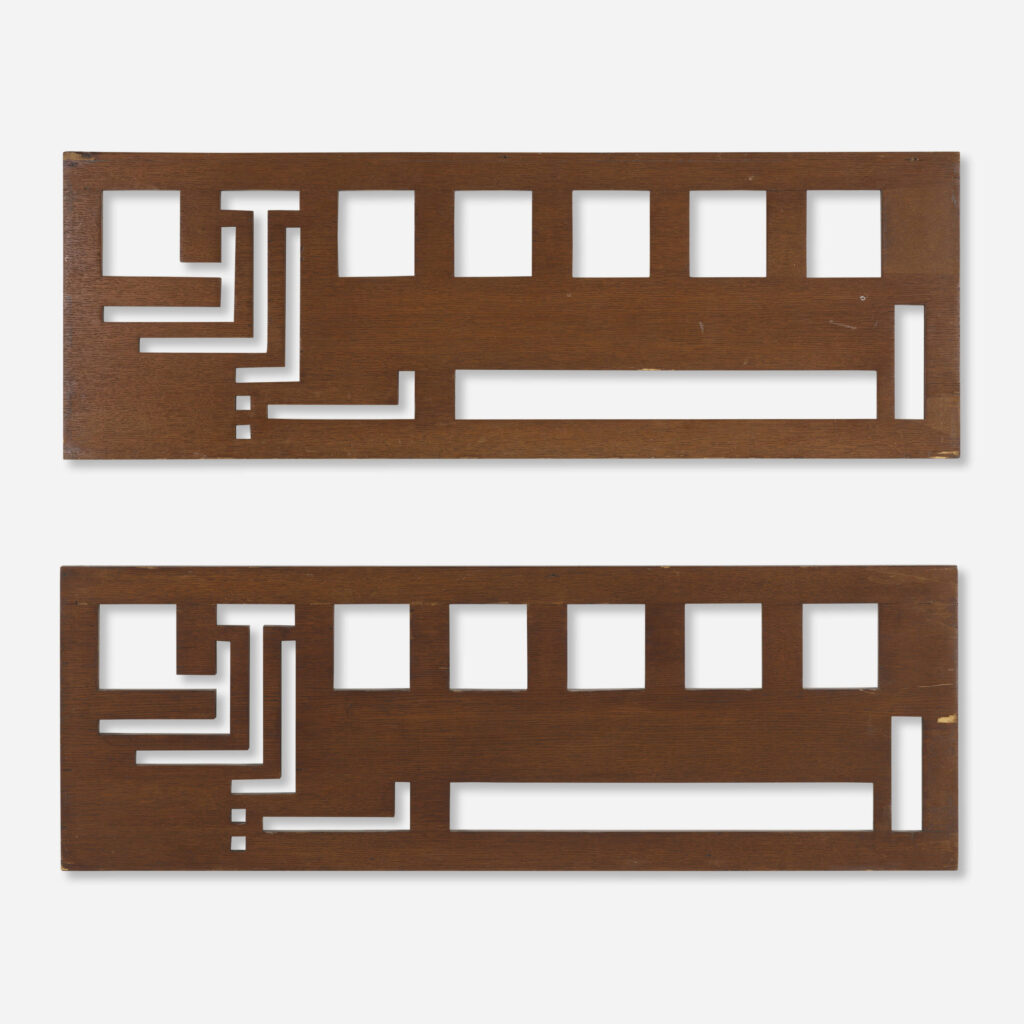

Seeing these Frank Lloyd Wright clerestory window screens from the New York Exhibition House, and being like, New York Exhibition House?? And I guess I somehow never clocked that the Usonian project kicked off with a fully furnished, 1,700-sq ft house built on the site of the Guggenheim Museum in 1953. The Usonian Exhibition House was supposed to be sold off and rebuilt somewhere, which didn’t work out [see above], and the plans were executed twice—for the Feimans in Ohio, and the Triers in Iowa—but that’s not important now.

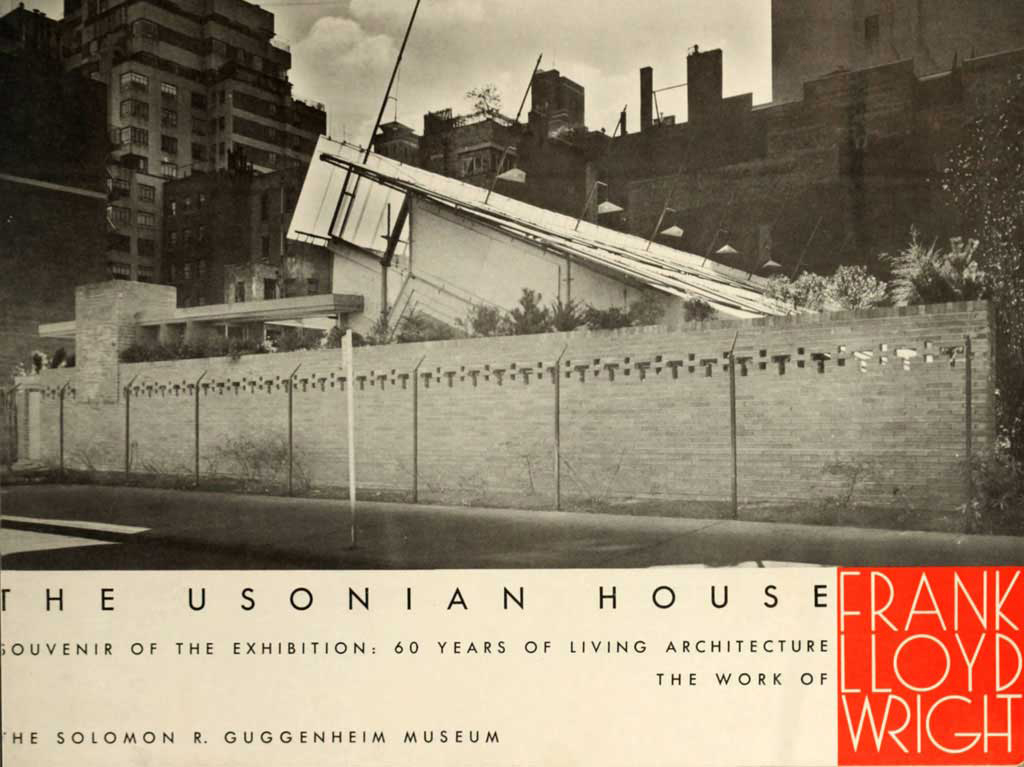

Because also—or rather, first—FLW built a pop-up, 10,000-sq ft exhibition pavilion, on Fifth Avenue.

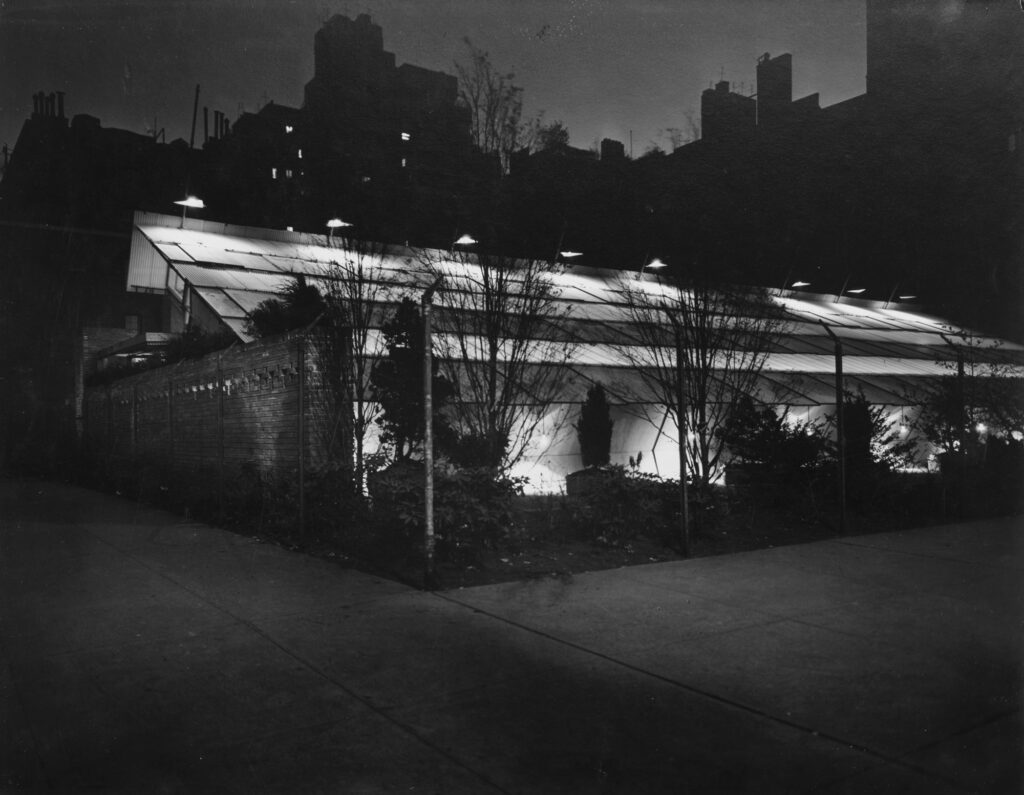

Called his first building in New York City, the pavilion held a traveling 60-year retrospective of Wright’s work. Within and atop walls of red concrete brick, Wright was the first in the city to use a new “flexible pipe structure” for the building’s skeleton. The single plane roof rose from nine feet along Fifth Avenue to 20 feet, and was clad in alternating bands of sandblasted wire glass and grey “Cemesto” panels, the same Celotex asbestos concrete panels used on the Eames House. Exterior lights shined down through the roof.

It is remarkably poorly documented, this pavilion, or at least meagerly published. Judging from their tiny 2017 exhibition on the House & Pavilion, the Guggenheim does not have very much. And in the timeline of the Wright building, the nighttime photo of the Pavilion is labeled as the House.

While interior shots are few, there is a large set of photos documenting the construction of the House and Pavilion by Pedro Guerrero, a friend of the builder David Henken, which are visible at Douglas M. Steiner’s vast Wright Library.

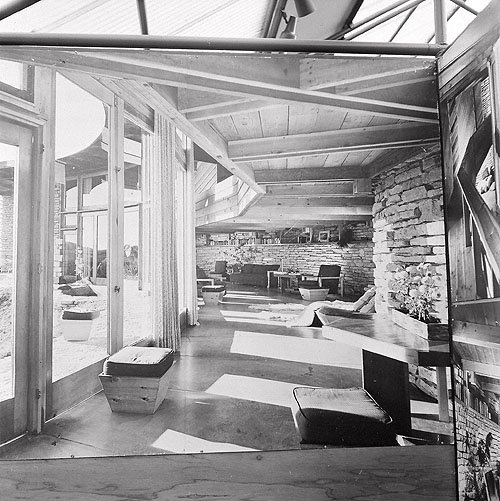

Here is one interior view, from the exhibition pamphlet. In addition to some models, the pavilion housed many photomurals, and some potted plants.

Truly we are living in the world Frank Lloyd Wright built, by which I mean sidewalk sheds.

The exhibition was so popular, it was extended for two weeks. The pavilion was so popular, the Guggenheim decided to keep it up until construction began on their new building. But in January 1954, the roof collapsed under the weight of some snow, and that was that.

Wright’s retrospective moved on to Los Angeles, where he erected another temporary pavilion at the Hollyhock House, the hilltop arts compound he had designed for Alice Barnsdall in 1919-21. There is more documentation of this one, including in color—the flexible pipe structure was red!

And photos of many of the photomurals:

Whether through popularity, utility, or the kind of benign bureaucratic neglect the municipally owned Hollyhock House was subject to, the temporary exhibition pavilion stayed up. It was only demolished in 1970. And yet, as Steiner noted, it was excluded from FLW’s catalogue of works.