I kept getting caught off guard by an aggro undercurrent in Maggie Nelson’s essay about Rachel Harrison in The Paris Review. [From 2020, in response to Harrison’s show, Life Hack at the Whitney, it was first published in the show’s catalogue in 2019. It’s been a long pandemic, and the stack of open tabs mocks me from the corner.] But I can’t let this one go by unnoted:

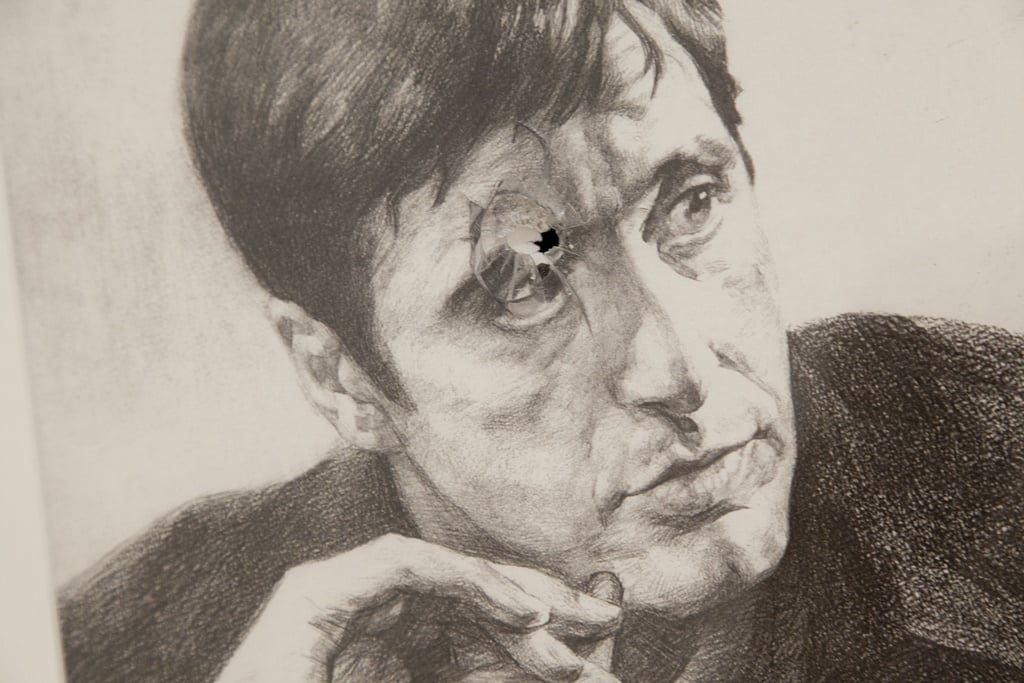

This current of nihilism or violence has been present in Harrison’s work for some time, via its excavation of America and Americana; in 2015, it became literalized, when actual bullets were fired into her work at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, by an ex–security guard who spray-painted and shot several pieces of art in the After Picasso: 80 Contemporary Artists exhibit before taking his own life. After defacing the art—including sending a bullet into the forehead of a framed drawing of Al Pacino in Harrison’s 2012 sculpture Valid Like Salad (a new, tragic echo of Davidson’s mop in the head)—the ex-guard, Dean Sturgis, sat in a folding chair and shot himself in the head (a new, tragic link to Circle Jerk).

Whatever urge toward defacement, whatever hostility toward art qua art, whatever exploration, however lighthearted, of American breeds of masculinity, celebrity, and sociopathy may have been at play in Harrison’s work (in 2007, she titled a show “If I Did It,” after O. J. Simpson’s much-maligned memoir)—all must now sit uneasily with the legacy of Sturgis, whose bullet holes serve to remind us that our everyday includes mortal threat and terror as much as it does remote controls and air fresheners.

Nelson makes it sound like this association with the Wexner Center shooting was foisted on Harrison’s work, that it’s been tragically linked, passive voice. But that elides the artist’s own agency, and her own decisions, and risks diminishing her own insights about her work, both before and after it was shot.

Though multiple works were damaged or destroyed in the Wexner Center attack, Columbus Monthly reported in March 2016 that Wexner director Sherri Geldin and other Ohio State officials refused to identify the damaged works, claiming it was a “‘trade secret’ exempt from public disclosure.” As far as I could discern, Harrison was the only artist to publicly acknowledge their work had been affected.

And she did it by making it part of the work. In April 2016 Harrison included the Wexner works in her unannounced show, More News: A Situation, at Greene Naftali. unconserved, with the bullet hole through the forehead of the fan drawing of Al Pacino as Tony Montana.

The Wexner works were in a gallery on the other side of dozens of Trump piñatas, another legacy we’re now all stuck sitting uneasily with. Besides the sculpture, one of the four Wexner Winehouse drawings was shot, and another was spraypainted. Brian Boucher’s artnet coverage of the show situation is the clearest discussion of the time of the works that were damaged.

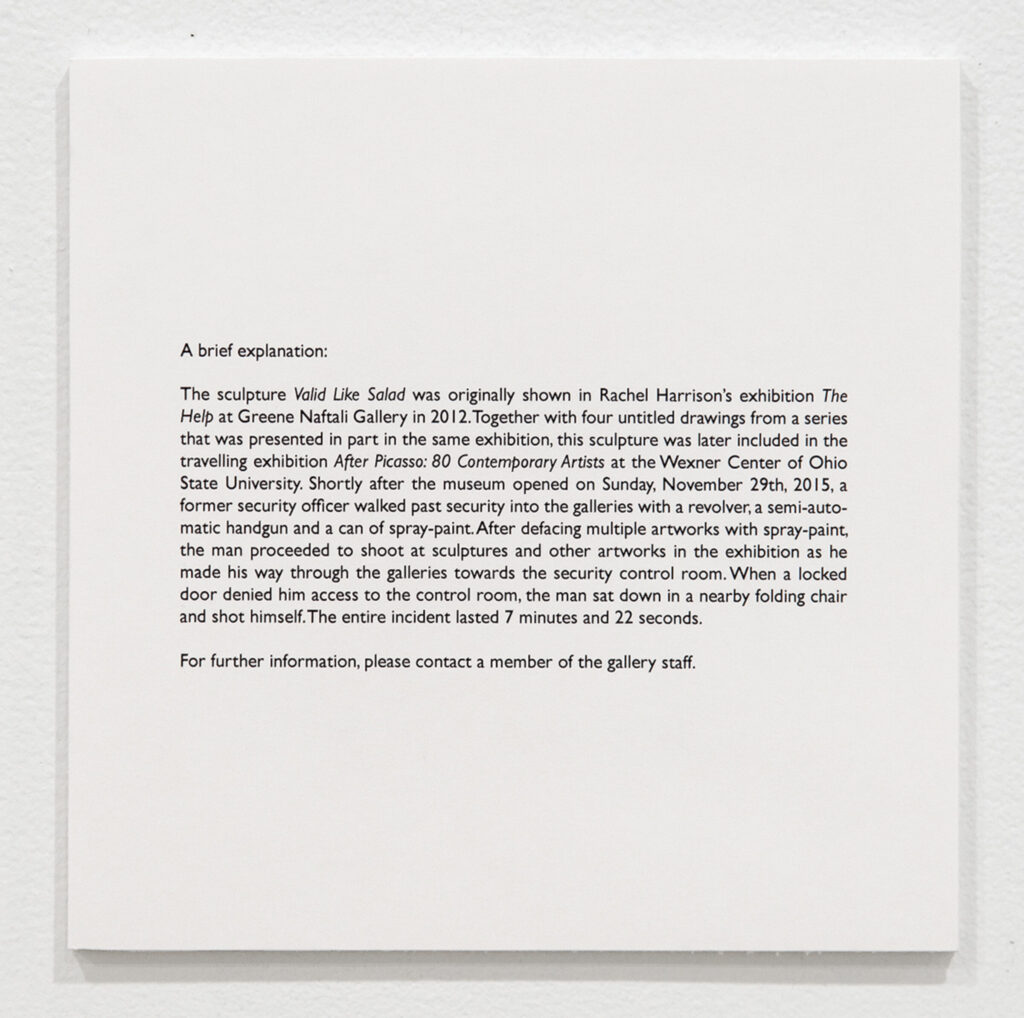

Laying out the sequence of spraypainting and shooting, thwarted plans and suicide in a clinically precise time frame, Greene Naftali’s wall text is somehow the most detailed account of the Wexner Center situation.

In 2016, Valid Like Salad was acquired by the Met, which abstracts the situation right tf out: “Valid Like Salad exemplifies Harrison’s long-standing fascination with male celebrities, on whose exaggerated machismo she casts a critical, feminist eye. Indeed, Harrison’s anthropomorphic monolith is partly an ironic re-interpretation of historical statues of so-called great men. An act of violence resulted in Valid Like Salad being damaged in 2015. Because Harrison decided to forgo conservation, the damage is now conceptually and structurally part of the work. To erase evidence of it would be to repress the very dysfunction Harrison seeks to lay bare in her sculpture.”

The attack on the sculpture is decentered, leaving only the damage, while Harrison’s decision is negative, “to forgo conservation.” I had assumed the irreplaceability of the Tony Montana drawing was at least a minor factor in her decision to keep it. But it turns out it’s not a drawing; it’s a print. The Met identifies the picture as a “digital print” and a “scanned print of a drawing.” Faced with the option of using a mechanical reproduction to erase, not just evidence, but history, did Harrison ask herself, “What would Walter Benjamin do?”

[UPDATE: Harrison’s gallerists at Greene Naftali have offered a correction; I had repeated an inaccurate description of the Pacino drawing as a “flea market find,” when it was, in fact, a gift. The artist has since clarified: “It was a gift from an acquaintance. I was told it was bought from an artist in Central Park as a gift for me.” Glad to clear that up, also to realize it was a scan.]

Benjamin wrote in 1940:

This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

In 2016, Harrison reversed the installation of her work from the Wexner Center shooting, turning the drawings and Valid Like Salad‘s backs toward the future, and their faces toward the past. Whether the angel of history is Amy Winehouse or Tony Montana, the storm is not what we call progress. Maybe a good idea for looking at the past is make sure not to not repeat it.

Previously, related, 2021: Better Read #036, Rachel Harrison’s Life Hack