Some time in 1988 before November, Glenn Ligon made Untitled (I Am A Man), which is called his first painting of a selected text, based on a 1968 civil rights protest poster he’d seen as a student in the local office of Congressman Charlie Rangel.

In November 1988, Jamaica Art Center visual arts director Kellie Jones’ proposal of sculptor Martin Puryear to represent the US at the São Paulo Bienal was announced. Puryear was the first Black artist to represent the US at an international exhibition. [He went on to win the grand prize and a MacArthur that year.]

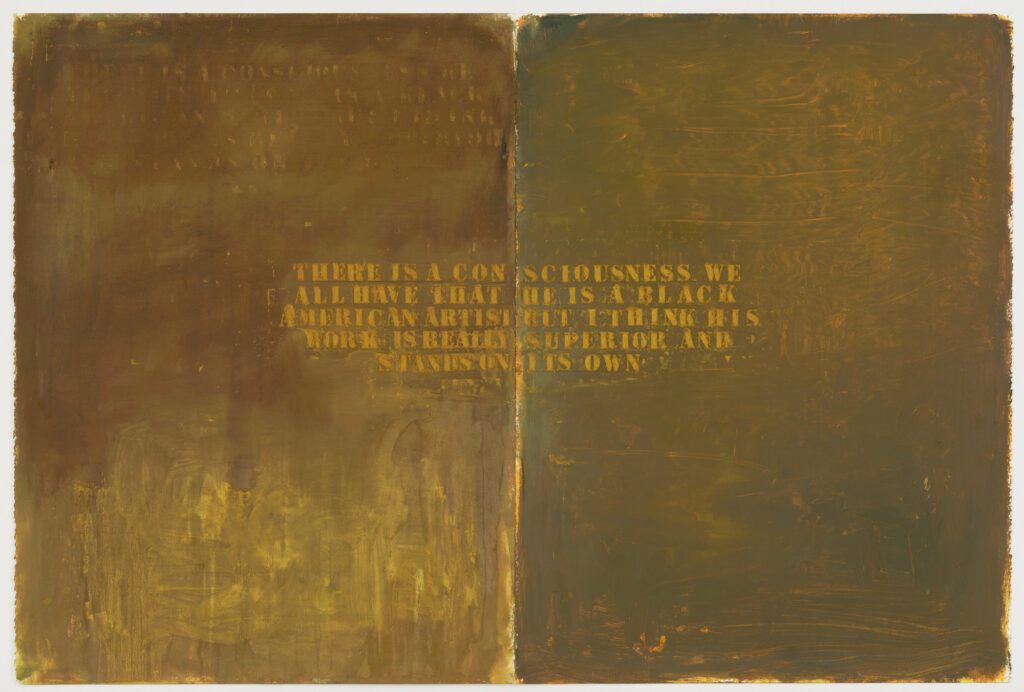

One of the ten members of the Federal Advisory Committee on International Exhibitions, which made the selection, was Hirshhorn Museum chief curator Ned Rifkin, who actually said, to The New York Times, “There is a consciousness we all have that he is a black American artist, but I think his work is really superior and stands on its own.”

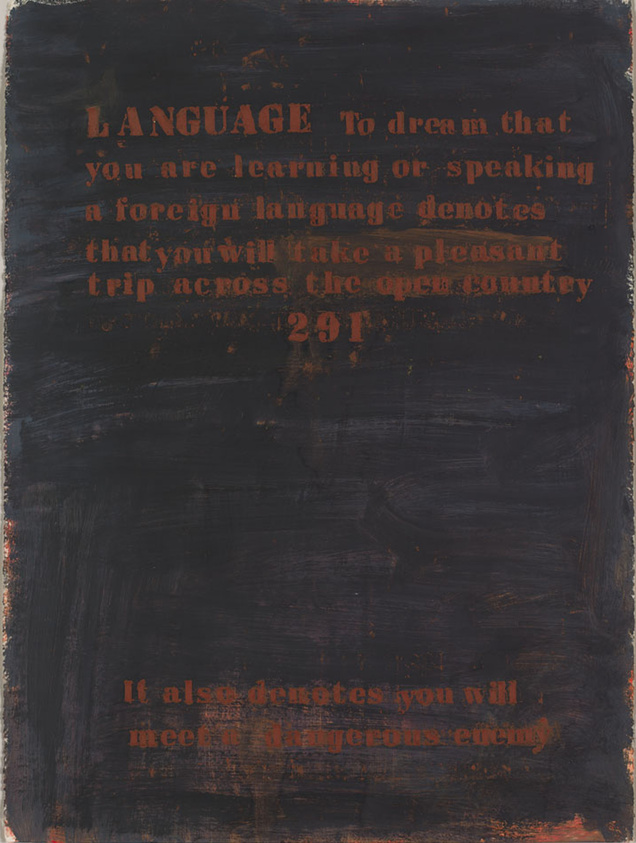

Also in 1988 Ligon was working on stenciling found texts, on paper. Including quotes from “dreambook” pamphlets, street handouts that coupled dream interpretations with advertisement for an underground lottery his father worked at.

And also condescending quotes by major museum curators published in the newspaper. Untitled (There is a consciousness we all have…) comprises two sheets of the same size as the dreambook painting above. It shows an early example of Ligon stenciling a found text multiple times. In a composition similar to No. 291 (Language), faint and effaced versions of Rifkin’s quote can be seen on the top and bottom, respectively, of the left sheet, while the right sheet seems to bear traces of marks made by pushing the stencil itself.

So it is that I only heard of this quote, and this work, this morning, while reading Kriston Capps’ extended reflection on the Hirshhorn in the Washington Post occasioned by the museum’s 50th anniversary. Capps’ reference sent me on a search for the work and the quote, and the curator and the context.

And I thought this is how it must have felt to first encounter Ligon’s work. Much is made of Ligon’s choices of text and the resonance of their sources, but it feels worth noting how much of that information exists apart from his paintings. Though he eventually began mentioning titles in his own titles, early sources like dreambooks and Ned Rifkin were untraceable and unrecognizable, at least to someone who didn’t live them. So their first reference is Ligon, who put them there, not the source he got them from. Which makes Rifkin’s quote even more outraging, offensive—and, for a young Black artist reading it, dispiriting.

In 1991 Ned Rifkin left the Hirshhorn for the High Museum in Atlanta, and Ligon was in his first Whitney Biennial. In early 1993, presumably before he showed Notes on the Margin of The Black Book at the Whitney Biennial, the Hirshhorn acquired their only Ligon works to date: a door painting, Untitled (Black Like Me #2), and Untitled (Four Etchings), both from 1992. The painting was loaned to the White House for four years beginning in 2009. The National Gallery of Art acquired Untitled (I Am A Man) in 2012.