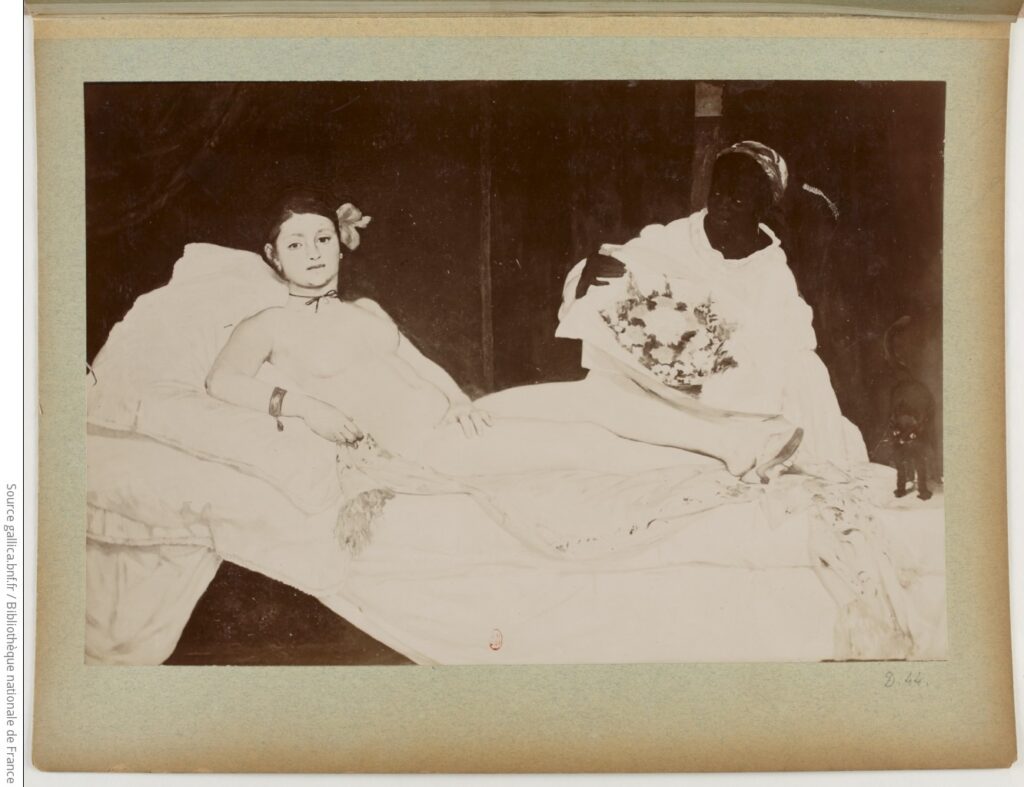

In the latest Irving Sandler Essay in The Brooklyn Rail, artist Alexi Worth lays out a fascinating theory about the revulsion contemporary critics expressed about Manet’s Olympia when they first saw it at the Salon in 1865: they were confounded by Manet’s depiction of full frontal lighting. Worth extends his observation from a 1971 essay about the “lantern gaze,” in which Michel Foucault reads Manet’s paintings as lit from where the viewer—and before that, the painter—stood:

Why was frontal light invisible—or uninteresting—to scholars? One reason is simple: Manet himself never “authorized” the topic. A secretive artist, Manet left few records, and never said a word about his reliance on frontal light. But Manet’s silence is only half the explanation. Perhaps more important, frontal lighting just seems unremarkable. Familiar. Normal. All of us, scholars and non-scholars alike, are habituated to bright frontal light. We see it all around us: in the faces of fashion models and TV anchors, in images by Andy Warhol or Nan Goldin, or for that matter in any flash-lit photograph.

“You could say,” Worth goes on, “to put it too simply, that frontal lighting looks like early Manet.” I’ll try to remember this the next million times I can’t unsee the ring lights reflected in the eyes of every youtuber and influencer.

Olympia‘s Wrongness, by Alexi Worth [brooklynrail.org]

Previously, related: On the first photographs of Manet’s Olympia

Previous Sandler Essay, unfortunately relevant: On Art & Autocracy