Look at this frog. Just look at it. A marble frog the size of a good spaghetti squash, carved with exquisite simplicity, with that flat mouth, the rear legs in relief like a pair of wings, THOSE EYES. It’s barely been published or shown—once at the Century Club in 1955? Does that even count?

And then in 2022 it pops up at Sotheby’s HK, out of a private Japanese collection, who’d bought it in 1991 from Eskenazi, and is hailed as an outstanding sculpture from the Shang dynasty, one of just three known Shang marble frog sculptures. Of course it would sell for HKD 28 million (USD 3.5m), almost 10x its original estimate.

And then less than a year later, a second Shang frog turns up at Sotheby’s NY, this one being “rare and exceptional.” And while it is equally outstanding, a second frog of three is, by definition, roughly a third as rare and exceptional as a single frog. And so it sells for roughly a third the price, $US 1.2m.

The ur-Shang frog, or at least the other one, belonged to Philadelphia lawyer Richard Bull, who, within a few years after WWII, assembled a collection of Chinese art under the guidance of “the great Hungarian Orientalist refugee scholar Alfred E. Salmony.” Salmony published the Bull Frog in his journal in 1957, giving it the early Shang dating, inferring an evolution of complexity, engraving, and naturalism compared to later Shang carved stone figures. But it sounds like he also couldn’t identify a species because he interpreted the legs as wings.

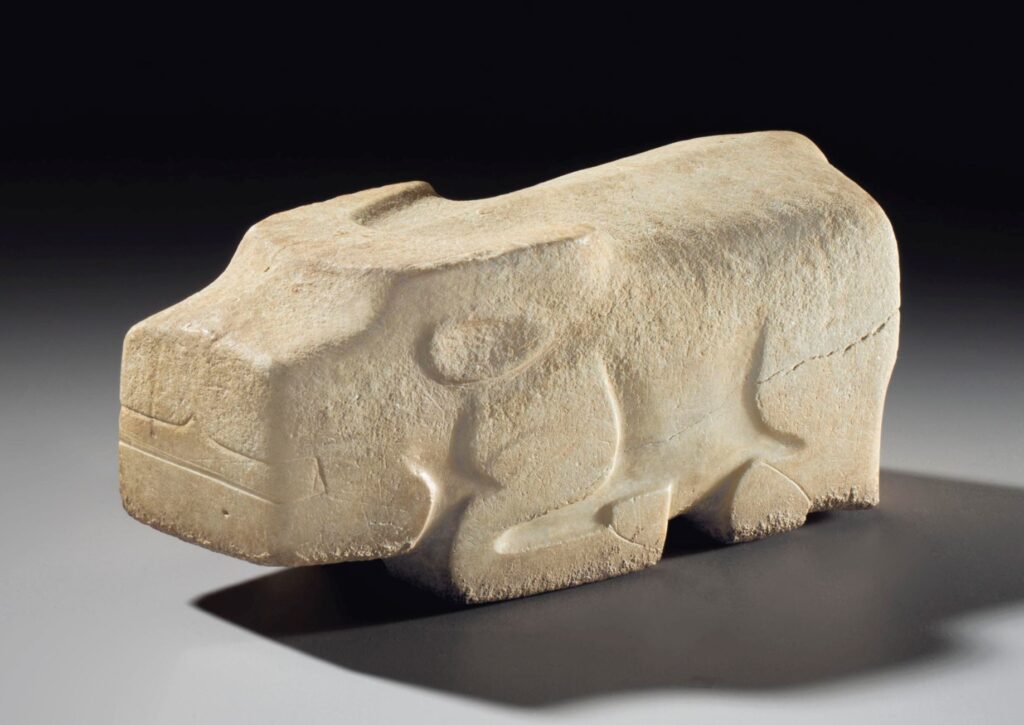

In 1965, Bull wrote about his collection for the bulletin of the UPenn Museum, praising his archaic frog “which would have delighted Brancusi.” This conflation of abstraction and primitivism sounded familiar even before I found Zhu Zhiruong’s 2024 analysis of Shang aesthetics that described a marble water buffalo, similar to one sold at Christie’s in 2013, as “full of naivety and innocence.”

The flat planes of their faces are not naive, but precise and deliberate. In every one of these naive, innocent, simplistic examples, the sculptor also made the decision to carve the subtle ridge of the animal’s spine. These animals look like this for reasons that are lost to us, but also because that’s the way their creators intended them to look. By the third frog, I’d think that’d be clear.

That Christie’s water buffalo text really emphasizes the reality that all these stone sculptures and almost all the bronze vessels which have become the Shang dynasty’s best known genre of artifact, were excavated from tombs in the 20th century. So much we don’t know about the frogs can be attributed to their being dug up and shipped off to market, stripped of their site, history, and archaeological context.

In 1976 archaeologists in Anyang discovered the tomb of Fu Hao, a consort and military leader to the late Shang king Wu Ding. It is the only intact royal Shang tomb, and it included hundreds of objects from Hao’s life as well as some made for her burial. It also included antiques, like a jade phoenix carved centuries earlier. So the late Shang elite were collectors, though not, it seems of marble frogs. Or maybe Fu Hao just didn’t like them.