After decades of tearing down medium-specific silos I’m not going to start rebuilding them now. And it’s entirely reasonable to look at Wolfgang Tillmans’ wide range of print formats and say that he has always been exceptionally aware of making shows that are also installations, and images that are also objects.

But by the time I made my way through Tillmans’ massive, catalogue raisonné-scale show that fills the Pompidou’s 6,000 m2 library, the pictures all felt familiar. The music, I love that for him. What I wanted to know more about are Tillman’s sculptures—and his painting.

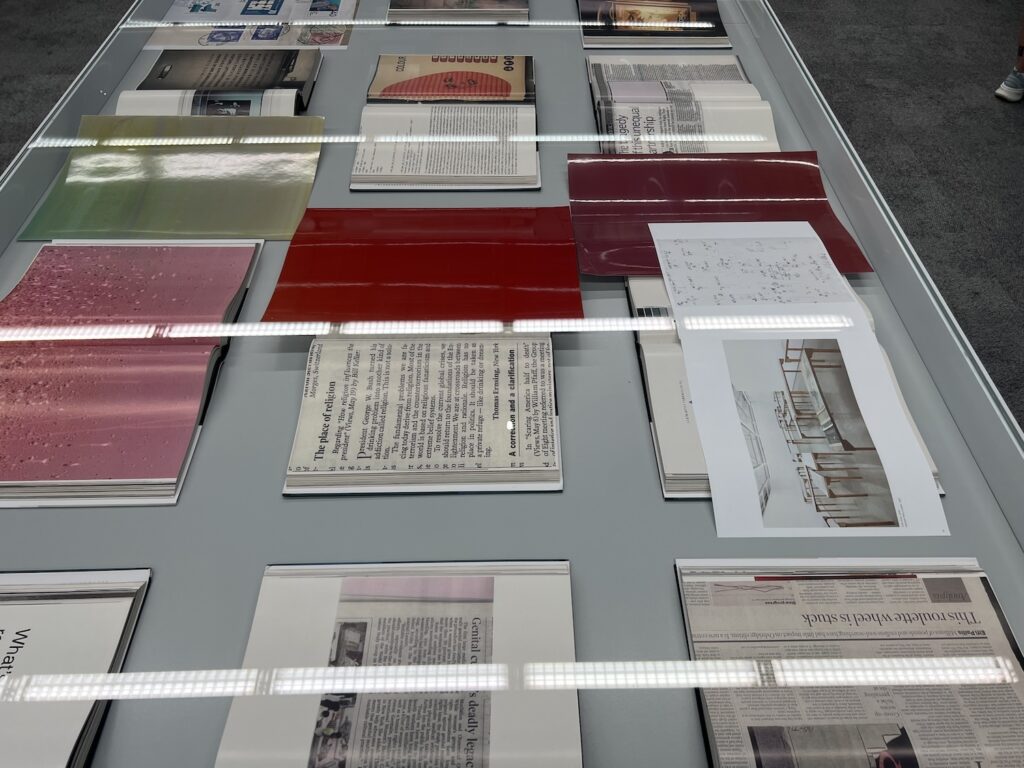

Tillmans has been showing scrappy wooden tables filled with newspaper and magazine clippings, books, and ephemera in his Truth Study Centre for twenty years. There was some of that at the Pompidou. But there were also vitrine tables, and the one above, with monochrome prints interspersed and overlaid with the books, a materially distinct composition that obviously crosses—or erases—medium boundaries. The books all had labels; I don’t remember the prints having them.

In a row of leftover 7.4m long BPI tables, one showing all 66 pages of Tillmans’ book, Concorde, and another filled with seemingly every book that ever used a Tillmans image on the cover, was a table with a mirror top. Tillmans says he laid down the mirror to showcase the ceiling’s impressive beams and mechanics. It is also extremely awkward for mirror selfies, though it was perfect for taking a photo of the person across from you. I considered offering to swap phones with the random guy across from me so we could both get our shots. A relational aesthetics machine. No label for the table.

I keep mentioning labels because it seems to matter. cTillmans’ show occupies the mostly—but not completely—emptied out space of the Bibliothèque publique d’information (BPI). There is a lot of awareness of the video portraits of BPI users Tillmans made and is showing on the monitors of rows of individual research computer stations. And there is some discussion of the two rows of library shelves Tillmans retained and filled with 12,000 retired books. Because there’s a label: Library shelves with an unusual amount of space around them, 2023/2025. I suspect the double date reflects the work’s idea & realization, but it does let me imagine Tillmans installing library shelves with an unusual amount of space around them before, somewhere else.

This is a good time to mention the carpet. In part 13 of the podcast [sic] for the show Tillmans describes the different colors and layers of carpet revealed by removing shelves, partitions, and other fixtures as a giant photogram of the organization of human knowledge. Whether he’s “drawing with light” in his abstract Freischwimmer darkroom prints or appropriating the geometry of a 60k sf carpet, Tillmans’ frame of reference is photography.

And then there’s this, the most straight-up sculptural concoction in the entire show: a curving element in quilted, purple fabric snaking through an acrylic maze, mounted high on the wall. I looked for a label for like five minutes, and there was none to be found. Something sculptural is going on here, and all over, and it was not going to be spelled out for us.

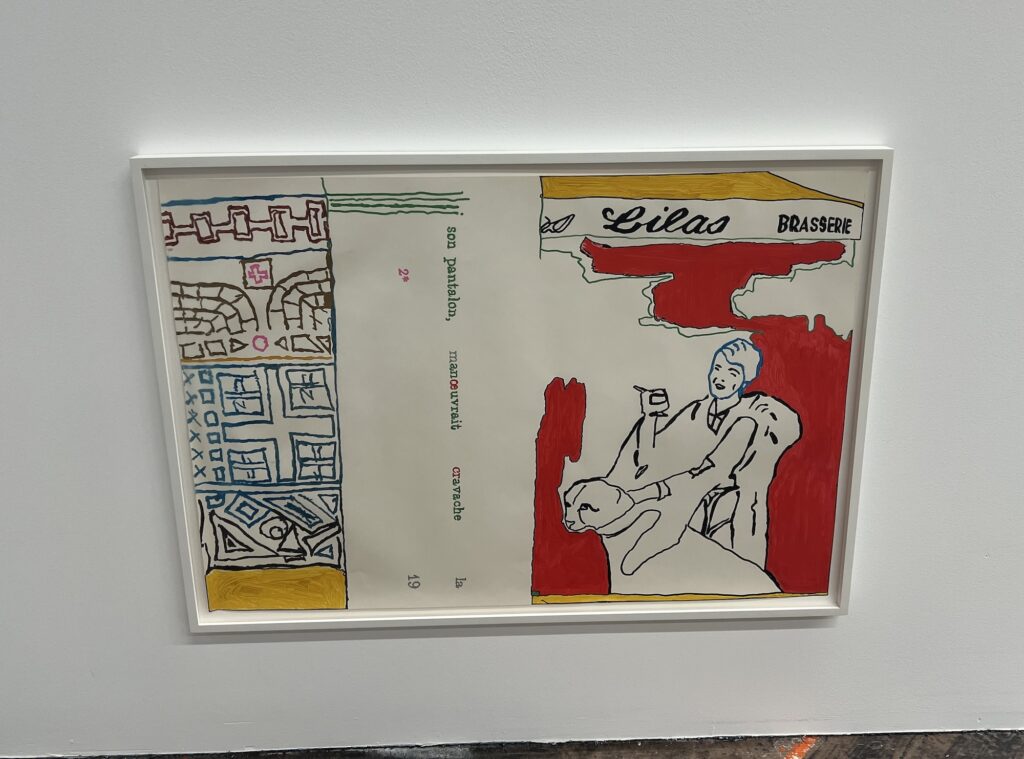

And the painting. Besides the abstract Freischwimmer, which are called drawings, there is a large ink on paper rendition of an abstract detail of a photocopy. But there is just one painting, one of the earliest works in his whole oeuvre, from 1987. Titled Son pantalon after the text running down the center, it looks like Tillmans traced projections or enlargements of three different images: a tile design? a cropped page from Guy de Maupassant’s 1883 story, À Cheval; and a photo of, I think, Josephine Baker and her pet cheetah in the Closerie des Lilas.

1987 was Tillmans’ photocopier era—some of my favorite works in the show are a series of Xeroxed variations of a photo of some white guy’s head, including a large version tiled together from a grid of A4 paper. Son Pantalon feels like one more aspect of Tillmans’ early explorations of what to do with the images he saw. It doesn’t seem like it’s been discussed or shown before, but it makes sense that it turns up in Paris. Was it included to mark a road not taken? The painting that made him decide to take up photography instead? Or is it a hint of what Tillmans might explore next?