photo: @bbhilley.bsky.social

“There is a six-panel folding screen, donated just recently by a Hiroshima family, whose gold expanses are streaked by black rain: the most terrifying abstract painting I have ever seen.” So wrote Jason Farago in the New York Times, after visiting the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum before the 80th anniversary of the US nuclear bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Bryan Hilley knew exactly what Farago was talking about, because last year, he’d seen it, too. And when I saw Bryan’s photo paired with Jason’s quote, I thought it, too, the most terrifying abstract painting I have ever seen.

But then I realized we were all exactly wrong. This is not a painting, and most importantly, it is not abstract. The way we immediately read it as such, though, underscores Farago’s larger point, which is that we largely lack the cultural references needed to recognize this object, where it came from, and why it’s as urgent to understand it now as it’s ever been.

This specific error is worth chasing down. The screen does not look like an abstract painting; abstract paintings look like it. Which is itself an overwhelming realization, until it isn’t.

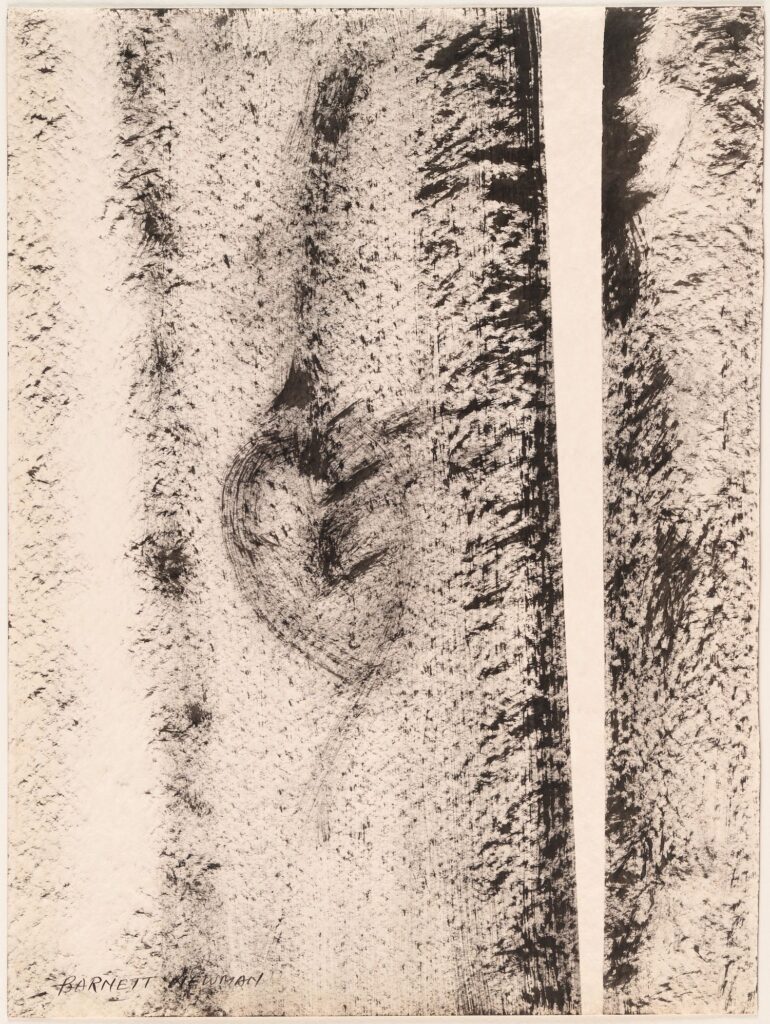

Faced with the world-ending future after a genocidal and nuclear world war, Barnett Newman somehow ended up painting things that looked or felt like this poison-streaked folding screen. The Whitney’s wall text for their early zip painting, The Promise (1949), lays this out: “Newman believed strongly in the power of abstraction to communicate the most dramatic and elemental aspects of human existence—the sense of alienation and vulnerability that followed in the wake of World War II, as well as an abiding faith in creation and new beginnings, as suggested by the title and composition of The Promise.”

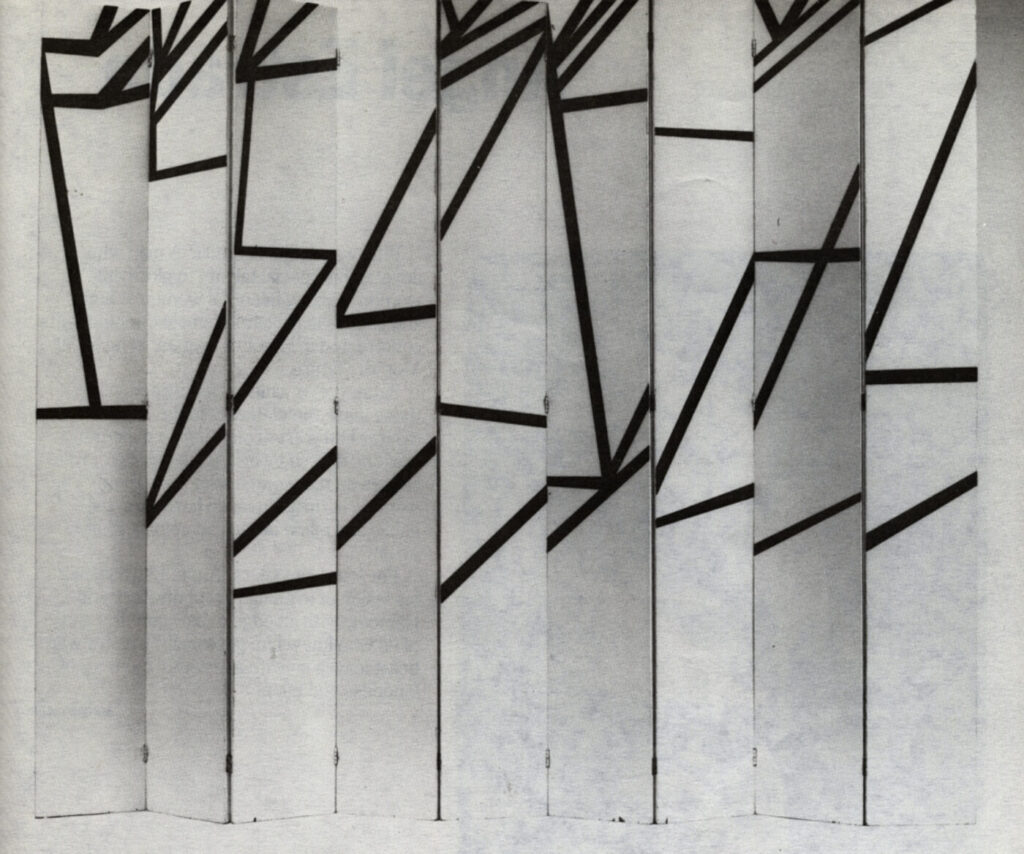

Beginning in France, Ellsworth Kelly developed a practice that looked abstract, but which is actually based on a transcription into paint of a singular physical form or visual phenomenon. Kelly made two folding screen-like paintings in 1951 whose form and image come from the fragmented shadows cast by handrails on a flight of concrete steps. Looks abstract, but is not.

Niki de Saint Phalle’s Tirs/ Shooting Pictures brought performative violence to action painting. Her nouveau realiste movement sought to work in Robert Rauschenberg’s gap between art and life. She wanted paintings to bleed. MoMA’s shooting painting came from her performance with Rauschenberg at the American Embassy in Paris in June 1961. Her own show, with a Tirs paintings shot by both Johns & Rauschenberg, opened ten days later.

In 1964, after winning the Golden Lion at Venice, and in middle of a tense world tour with Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Rauschenberg painted his second to last combine in Tokyo, live on stage, in a four-hour performance/interview at the Sogetsu Art Center. With Fujiko Nakaya assisting, Rauschenberg answered 20 questions from critic Yoshiaki Tōno only by mutely painting and affixing objects to a six-panel gold screen. White drips of paint around a speedometer, a sign about student protests, and golden Coke bottles, fronted by the RCA dog on a bicycle seat are not the most terrifying abstract painting anyone’s ever seen.

From Hiroko Ikegami’s deeply researched account of Rauschenberg’s 1964 world tour, it sounds like the combine performance was a stressful, specific mess, and also part of a larger failure of alienation and noncommunication. Rauschenberg fought with Cage & Cunningham, had an invitation for a gallery show rescinded within days of receiving it, and left Tokyo’s art community disillusioned and dissatisfied with the triumphalist American avant-garde he embodied. It was a sentiment that echoed more widely in Japan, in protests against the US military and the Vietnam war.

It was also the very moment, twenty years after the first bombs, when the visual records and evidence of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, long suppressed and ignored, rode a wave of anti-nuclear activism into the global consciousness. Black rain [「黒い雨」/kuroi ame] was the title of Ibuse Masuji’s 1965 novel about a couple, displaced from Hiroshima and desperate to help their niece marry, who try to cover up her exposure to the nuclear fallout before sickness inevitably takes them.

The Masuda family that owned the screen put it away almost immediately after the war, and it stayed in storage, unknown and unseen, for seventy years. A couple of years before they brought the screen into public view, the art world briefly convulsed over zombie formalism, a wave of empty, process-based abstract painting. A standout among this hapless trend was Lucien Smith, who called his canvases sprayed with a fire extinguisher Rain Paintings.

The shock the black rain-streaked screen generated when it emerged was not aesthetic, but material. It turns out physical evidence of black rain is extremely rare. Its composition, the range and location in which it fell, all remain largely unknown. Japanese news reports on the screen’s existence and exhibition center on the scientific analysis of the black rain traces, and what the findings, still meager, reveal about the aftermath of the bomb.

If this screen the most terrifying abstract painting ever, it is only because we cannot recognize or understand direct physical evidence of the most terrifying violence ever when it stands before us. Art is all we have, and it is not enough.