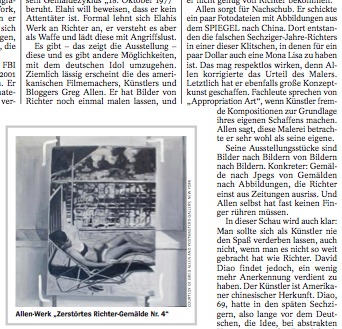

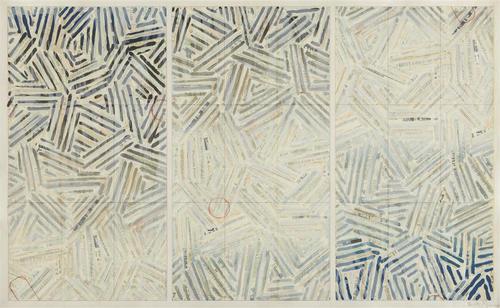

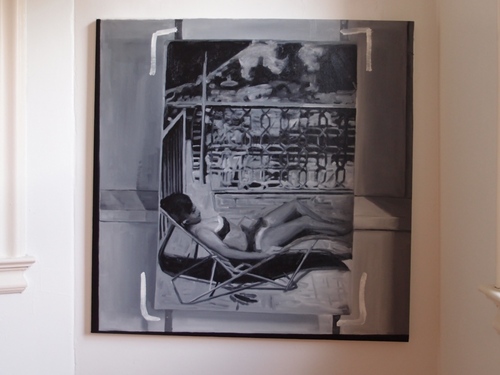

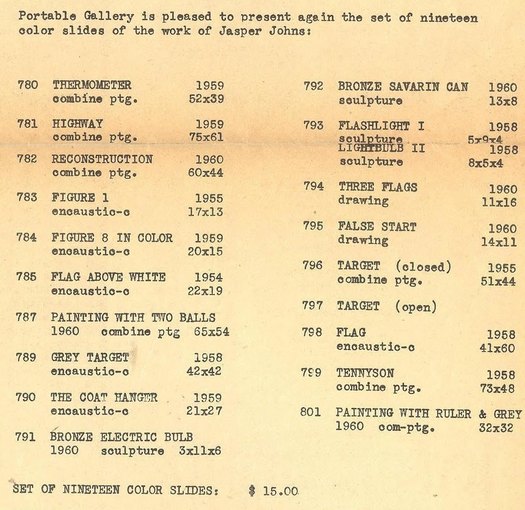

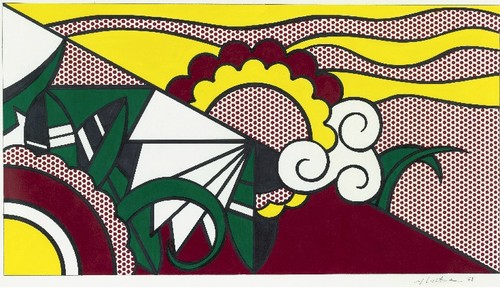

Roy Lichtenstein, Composition, 1969, image via sothebys.com

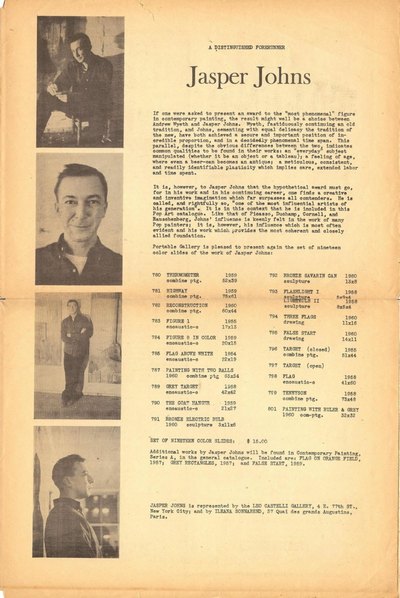

With the confluence this week of an incredible-sounding retrospective in Chicago and a bonkers-sounding sale at Sotheby's, I was reminded of one of the weirder things I stumbled across during a dive into Leo Castelli's papers at the Archives of American Art: the bathtub Roy Lichtenstein was commissioned to make for the St. Moritz penthouse of awesome playboy industrialist collector photographer wackjob Gunter Sachs.

According to a letter Sachs sent to Lichtenstein from Paris on October 3rd, 1968, the two had met in Southampton that summer, and they'd already discussed commissioning some paintings for the soon-to-be-legendary Pop Art penthouse Sachs was constructing in the tower of the Palace Hotel. While Avedon and Warhol were creating portraits of Sachs' 2nd wife, the then still-smokin' hot Brigitte Bardot, Lichtenstein was given the bathroom.

Specifically, Sachs wanted him to make some enamel painted panels to go around the tub and sink in the master bath. And he had put together some ideas:

If you permit I would propose that the painting on the large side of the bathing-tub (60x200 cm) should show a girl's face, perhaps with tears in her eyes, looking at a lake with a swan - a kind of modern Leda. On the little side of the bath (60 x 110 cm) I could very well imagine, e.g., a sunset or a moonset over a calm lake. The painting under the lavatory (60 x 200 cm) could figure a landscape in a thunder-shower. In all these paintings, however, it is very important that you respect accurately the dimensions indicated below in centimeters and inches.

OK, then! Anything else?

Crying Girl, 1964, enamel on steel, via milwaukee art museum

At first I was kind of blown away by Sachs' audacity to dictate the contents of the images, but then I figured that these were all close enough to subjects Lichtenstein was already doing at the time that it might not be so WTF-ish. [One of the artist's first attempts at enamel-on-steel production was Crying Girl, a painting produced in a multiple of 5, in 1964.]

Oh, and also, there was this: "As I am obliged to finish the apartment before Christmas, it is very important that I get your paintings till November 2nd, 1968." And he'd run the deal through Ileana Sonnabend in Paris.

Apparently Castelli, Lichtenstein, and their lawyer all jumped to work, because a contract went back to Paris within the week agreeing to sell one set of drawings and authorizing Sachs to fabricate one single set of enamel panels at his own expense, with payment due in full upon receipt of the drawings.

And then they hustled the drawings to Sachs' Paris secretary, even though the contract hadn't come back. And Sachs wasn't replying to anything at all, and then in December there's this increasingly testy series of letters demanding payment and signed contracts, which have not been forthcoming, even though the drawings were hurriedly finished and delivered.

"I must tell you that Roy is personally offended by your failure to act," wrote Lichtenstein's lawyer Jerald Ordover. A lawsuit was threatened, even though both Leo and Roy found it "most distasteful."

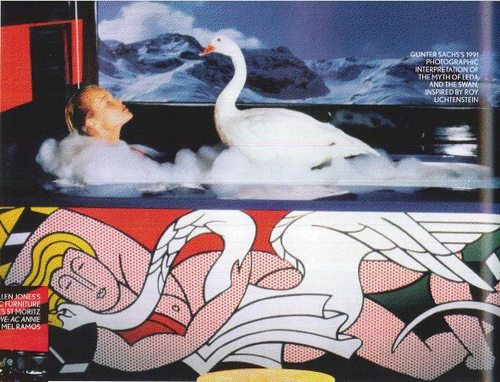

Leda and the Swan, 1969, enamel, 61x311cm, image: roylichtenstein.org

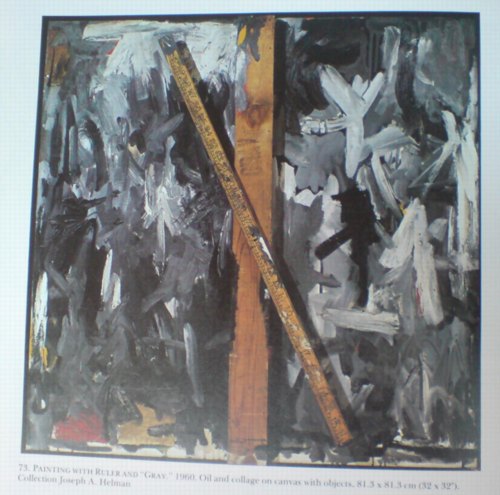

It's not clear how, but things must have worked out, because the works exist. And they turned out pretty much just as Sachs ordered them. Leda and the Swan [above] is two steel panels that could fit around a tub. And the sink piece, Composition [top], was actually in the Sotheby's sale Sachs' family held this week, a year after Gunter took his own life rather than succumb to what's believed to have been Alzheimer's. [It sold for 541,000 GBP.]

UPDATE: Oh, this is interesting. Here's part of the Sotheby's catalogue description for Composition:

Lichtenstein, alongside Warhol, sought a pictorial vocabulary embedded in modes of mechanical reproduction. However, unlike Warhol, who pioneered the silkscreen process to transfer his images to canvas, Lichtenstein set out by magnifying and transferring his sketches by hand in a painstaking process that insistently removed all the expressionistic detail of brushwork, further divesting the image of naturalistic representation. Composition, based on Collage for Leda and the Swan, 1968, is a consummate example of Lichtenstein's Modern Paintings series and of this technique of reproduction.

...

As Lichtenstein played down the idiosyncrasy of the artist's hand in favour of uninflected surfaces that replicate the look of the machine-made, we are compelled to venerate the movement and melody within this picture's unique composition. [emphasis added on the parts that are not applicable to this artwork.]

Ah, no. These panels were authorized by Lichtenstein, but fabricated by Sachs. Here's Gunter: "For the technical execution of your design in enamel I found an excellent German manfuacturer who will be able to transform your painting in a congenial work of Modern Art."

And here's the artist's attorney, Jerald Ordover, writing:

to set forth [Lichtenstein's] understanding of the terms of your commission to him to create the designs, in the form of working drawings, for the fabrication of three (3) enamel plaques...

...You are to have the plaques made from the drawings at your sole expense.

Which, yes, having them fabricated sight unseen in a German factory from drawings is certainly a process for insistently removing the expressionistic detail of the brushwork that plays down the idiosyncrasy of the artist's hand. And almost as interesting as the painstaking process by which the auctioneer insistently claims the artist's hand as a selling point, especially on work where the reason it looks invisible is because it was explicitly absent.

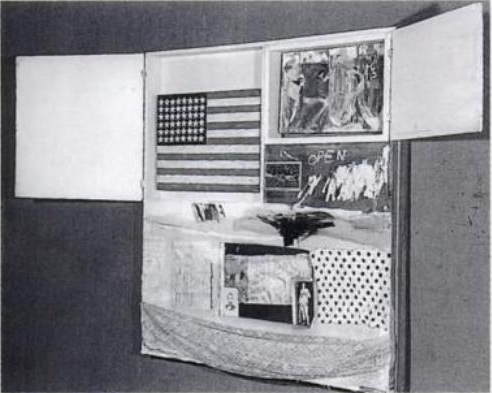

Nov 10, 2011, Lot 225: Collage [sic] for Leda and the Swan, image: sothebys

And the market seems to notice. Last fall Sotheby's actually sold Collage for Leda and the Swan, a full-scale work on paper for the short end of the tub [60x110cm]. Sachs had apparently gotten rid of it early, because its provenance shows it floated through several dealers' hands before settling down in 1989. Though called a collage, it looks to me like a straight-up drawing, overflowing with artist's hand. Which drew pencil lines, then traced them with marker and filled in the rest with acrylic. And it's signed. So it sold for $446,000.

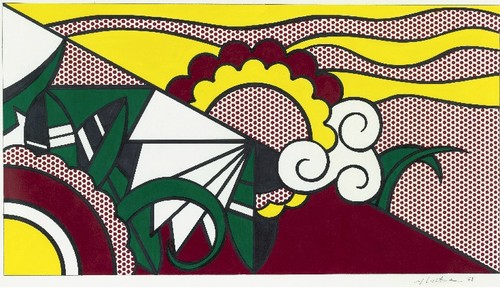

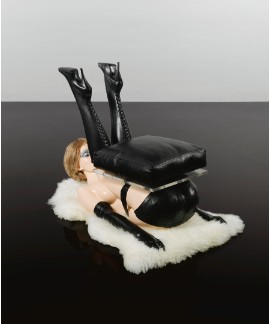

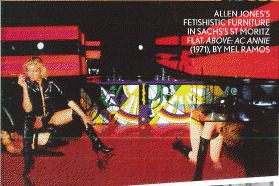

Lot 14: Allen Jones, Chair, ed. 6, est. 30-40,000 GBP, sold for 836,450 GBP [!!]

And though I haven't been able to find installation shots wacked out bondage furniture artist Allen Jones tells Sotheby's that he saw them in situ:

Gunther Sachs invited my wife and me to stay in his penthouse at the Palace Hotel, St Moritz, soon after he had acquired my sculptures. It was the most ritzy place I had ever been in. One wall of the apartment seemed to be entirely glass, with a breathtaking view of the Alps. There were Lichtenstein panels round the bathroom, a flock of Lalanne sheep on the carpet and the set of my sculptures. Giovanni Agnelli was at the party and wanted to stay in the penthouse, but Gunther had said that the Joneses were there. Agnelli, thinking that he meant my sculptures, said "don't worry, I won't touch them!" Prominent in the apartment was a large, bullet-proof glass panel with one side splintered in several places. Gunther used to stand behind the glass and invite close friends to shoot him. Their names were inscribed on a plaque next to the glass.

Hahwwhawaitwhaa? Are you kidding me? Where is this bulletproof glass panel and plaque now? Because THAT is what I want to buy.

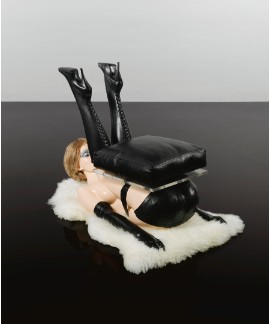

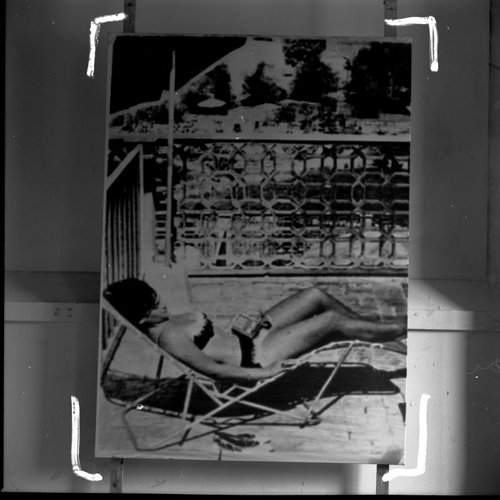

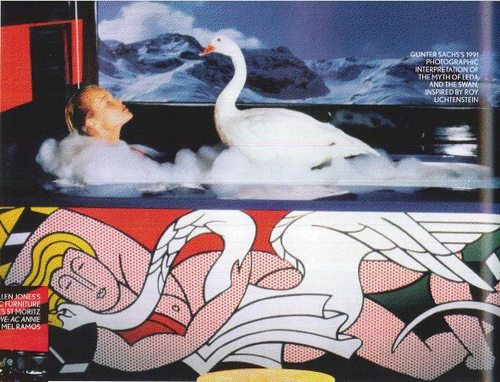

UPDATE UPDATE: OK, maybe my problem is I gave up searching for photos before the Sachs auction. Because in a preview article for the sale, British Vogue ran a 1991 photo by Sachs, of a Leda and a swan in the tub. I didn't realize the Lichtenstein panels went around the base of the tub; I thought they were backsplash-type deals. But with those views, well.

Also, Vogue gushes about "Roy Lichtenstein kitchen-unit fascias and bath panels," which what? I guess the delay in payment wasn't a fatal blow to their friendship, or maybe Sachs commissioned a kitchen from the artist as a make-up. Or maybe a bar, because who needs a kitchen, it's the Palace Hotel, and this bar in the S&M living room looks very Deco-era Roy to me.

And finally, Vogue doesn't mention a plaque, but does say that guests who shot at Sachs would autograph their bullet hole. And if these aren't bullet holes made by the glitterati of Cold War Europe, then why are they in Sotheby's promo video?