Early work, commercial work, disowned work, and destroyed work are not relevant to an artist’s work, except when they are.

Tiffany & Co. building on the corner of Fifth & 57th, c.1940 via nypl

I did not know that Bonwit Teller was owned by Walter Hoving, who bought it in 1946, and who also bought Tiffany & Co. next door in 1955. From the family. The store was in trouble, and he turned it around, turned it into the Tiffany’s we know today. Hoving was a crack retail guy. His son Thomas became director of the Met. Hoving had Bonwit’s window dresser Gene Moore take over Tiffany’s windows, too. Bonwit’s had 16 windows on Fifth Avenue & 56th St. Tiffany’s had two on Fifth and three on 57th.

Bonwit Teller building, 721 Fifth Avenue, on the corner of 56th Street in 1956. Destroyed by Donald Trump.

Dali did some Bonwit’s windows in 1938. Duchamp did a window display for Brentano’s to promote Breton’s book in 1945; it had to be moved to Gotham Book Mart. Here is a long discussion of shop windows, Benjamin, flaneurs, and capitalist spectacle. [Brentano’s was Scribner’s before, and is a Sephora now.]

Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil did windows for Moore at Bonwit’s. And Rauschenberg and Johns did after that. Here is the set of amazing blueprint monotypes Bob and Jap did for Bonwit’s in 1955, which Gene kept. [1955 was also when Warhol started doing Bonwit’s windows.]

I’m going into this now because I finally got a copy of Gene Moore’s 1990 coffee table memoir, My Time At Tiffany’s, and it talks about the artists he worked with, and how he was the first window dresser [he preferred “window trimmer”] to give artists credit. And how he also showed their “‘serious’ work,” with credit, a rental fee, and no commission if it sold. And he has a chronology of all the windows he did for Tiffany’s.

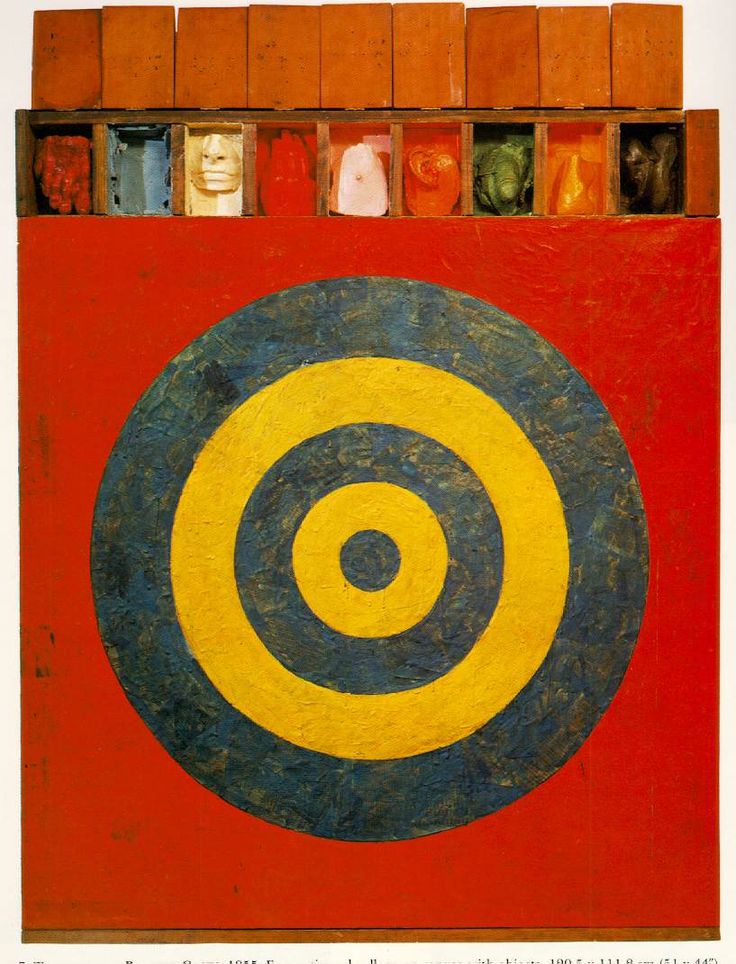

Target with completely unrelated and painted Plaster Casts, why do you even ask?, 1955

So here are all the Tiffany windows Rauschenberg and Johns did under their pseudonym, Matson Jones, and what Moore said about the projects and working with the artists.

jan 2017 update: via an interview in the Observer, Tiffany’s current VP of visual merchandising Richard Moore [no relation, apparently] has released four previously unpublished images of Matson Jones windows. They’re added and noted below.

Jasper Johns Blue Ceiling, Matson Jones, 1955

Here is what Moore said about working with artists, including Johns and Rauschenberg:

Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns called themselves artists but were unknown when they first came to see me. [Hmm. RR had shown at Betty Parsons and MoMA by 1951. -ed.] Rauschenberg came first. [And Weil? -ed.] He’d been down to Black Mountain College in South Carolina [sic], had heard about me, and came to my office at Bonwit’s. He’d been doing work with enormous sheets of blueprint paper. He’d take these sheets and lay all sorts of things on them, flowers and ferns, sometimes a body. I used them in the window’s at Bonwit’s.

I liked Rauschenberg. He was very boyish and open and seemed crazy, like me, maybe even a bit more. During the period Rauschenberg was contributing to the displays at Bonwit’s he met Jasper Johns. They became friends [sic] and shared a loft downtown [sic]. Johns was less outgoing than Rauschenberg, but I recognized fragments of my own past in his story. He was from the South, born in Augusta, Georgia, and raised in Allendale, South Carolina. His parents had divorced, and he’d been raised by relatives. In the warm monotony of that quiet southern town, he’d decided to become an artist. There were no artists or art near there, so he’d left, come north to New York. When he met Rauschenberg he was working in a bookstore, but Rauschenberg taught him how to live the way I’d lived back in the days of the Southern Cross and the Guaranty Trust-paint until the money runs out and then find temporary work.

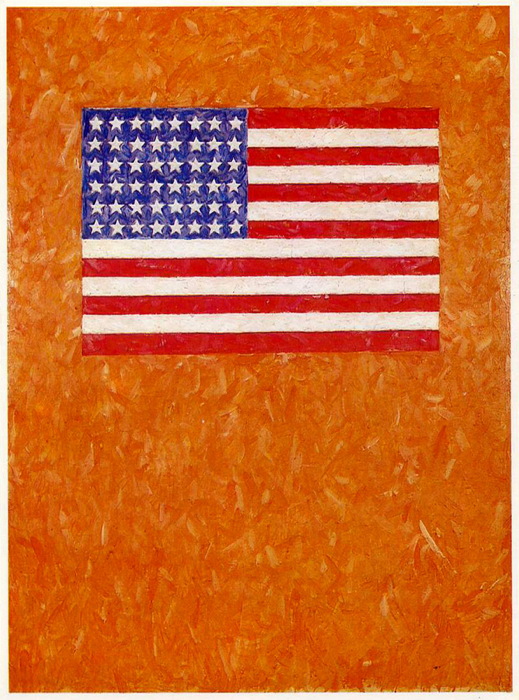

Flag on Orange Field, 1957, collection: Museum Ludwig, Cologne

During the same period of the 1950s Rosenquist and Warhol, Rauschenberg and Johns-the artists who shortly gave birth to the Pop movement-worked with me, most of all at Bonwit’s.The first showings of Johns’s paintings were in exhibitions I organized at Bonwit’s. [Hmm. Rauschenberg’s combine, then titled Construction with J.J. Flag was in the annual show at Stable Gallery in 1955, so. -ed.]I’d ask him for a painting, he’d bring one up to the store, and I’d put it in one of the windows. He was then doing lots of flags and targets; in 1957 I showed Flag on Orange Field in a Bonwit’s window. Sometimes Rauschenberg and Johns helped put together displays. They worked on a popular set of Bonwit’s windows that had house painters up on ladders spilling paint own onto mannequins wearing coats, the colors of the paints matching those of the coats.

[Moore notes that it was against the law for women to work after 10pm, and since window trimming was an overnight job, it was all male. I note that at the time Rauschenberg said he used house paints in whatever leftover colors he found. -ed.]

For Tiffany’s, Rauschenberg and Johns served as a kind of display house. I’d tell them what I wanted, and they’d go off and make it. I never knew which of them did what, they worked so closely together, even sharing the same joint pseudonym, Matson Jones, which I think they made up from their mothers’ maiden names. [At least half right. Johns’ mother’s maiden name is Riley. -ed.] They started using that name when they began to get recognition as artists-they didn’t want their commercial work confused with what they considered their real art.

Commercial art: the problem, of course, is the merchandise in the windows. At Bonwit’s the weekly selection of the merchandise to be displayed involved the fashion market, visits to showrooms with designers, discussions with buyers, the merchandising manager, and department heads, lots of talk, lots of planning. All this was necessary because at Bonwit’s I was actually selling something; at Tiffany’s, I’m not selling anything, at least not consciously. The selection of the merchandise to display at Tiffany’s takes place in relative silence. On the days before the displays are to be installed, I walk alone through the store, up and down the aisles, looking for items that might fit with what I have planned. It’s a well-stocked store, and i’ve never had problems selecting merchandise to work with my windows. [My Time At Tiffany’s, pp. 69-70.]

Yes, “merchandise”, but also, “my windows.” Moore never made sketches or even specific plans, but he sees himself as the artist here, not Rauschenberg, Johns, Matson, or Jones. And yet.

Here are the seven Matson Jones windows, with Moore’s descriptions of them:

1956

August 30: Cave scenes

Caves are fantastic: you can feel more solitude in a cave than almost anywhere else. I was remembering a movie I’d seen years ago in Birmingham, a 1916 film called A Daughter of the Gods. It starred Annette Kellerman-she was known as “the Diving Venus”-and it was set in Bermuda caves. I fell in love with those caves, the shadows and glimmering water, and thought of them often. Since I believe in looking up old loves I went down to bermuda in 198 to visit the caves where the film was made.

Rauschenberg and Johns made me five caves of plaster with embedded cast leaves: a cave of ice, of solid stone, of black coal, wonderfully dark caves in which I placed pieces of jewelry-imagine finding a jewel in a cave-that shone with all their might against those eerie backgrounds. [p.77]

And in the NYT:

Speaking of his fantastic “diamonds-in-water” display, Mr. Moore said: “This is the way my mind works. I thought: ‘Diamonds. White, cold. Ice.’ So I built an ice-cave background out of mirror splinters, got a water tank and put the diamonts on top of round platforms so they seemed to float like icebergs above the surface.”

Then he ran out to a fish restaurant, rented an air pump and installed it under the water to make bubbles. “I had to crawl into that window every day to wipe off the diamonds,” he said.

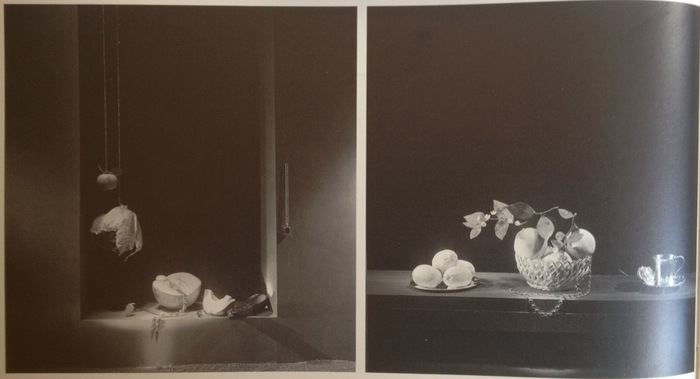

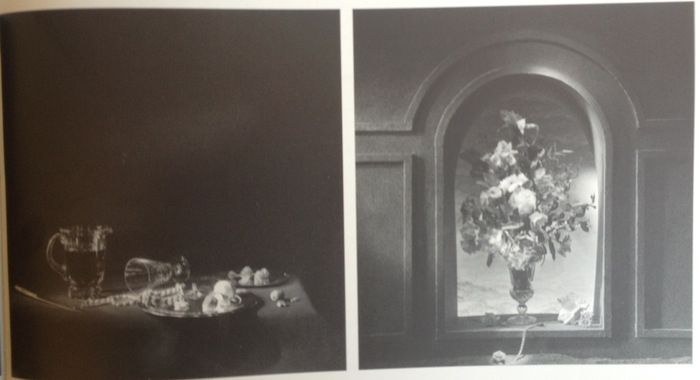

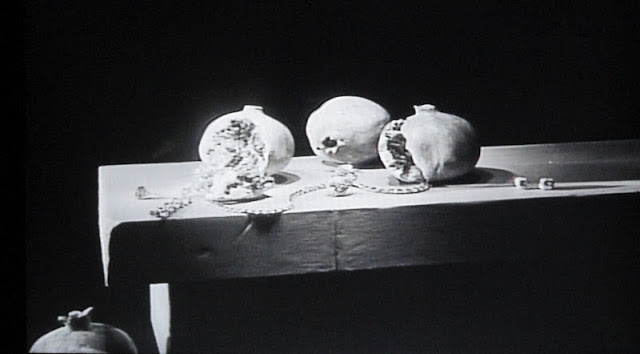

November 9: Recreations in dimension of 18th-century still lifes

I’d found an old book on seventeenth-century [sic] still lifes and decided to recreate those paintings in what I called dimensional paintings: accurately recreate them in three dimensions. I asked them to cast a pomegranate, a cantaloupe, a lemon, a cabbage and then paint them to look as real as possible. I wanted those objects to have a true painterly quality. For the cabbage they made each leaf separately and then put them togehter. With autumnal light and an ageless stillness, those windows worked wonderfully. [pp. 77-80.]

November 29: Christmas.

[Welder Judith Brown’s] angels appeared in one window, the reindeer head in another. In the third window I used a balsa-wood reproduction of Notre Dame by Jordan Steckel, a sculptor who did work for me at both Bonwit’s and Tiffany’s, and called on Rauschenberg and Johns to make me a forest for the fourth. The forest was full of icy trees, dark and menacing. They made the ice using Duco cement, which looks like ice when it dries. There in that forest I set up an orchestra of gold and enameled monkeys standing on stumps playing their instruments. I painted the backdrop sky myself-dark and kind of spooky. [p. 80.]

1957

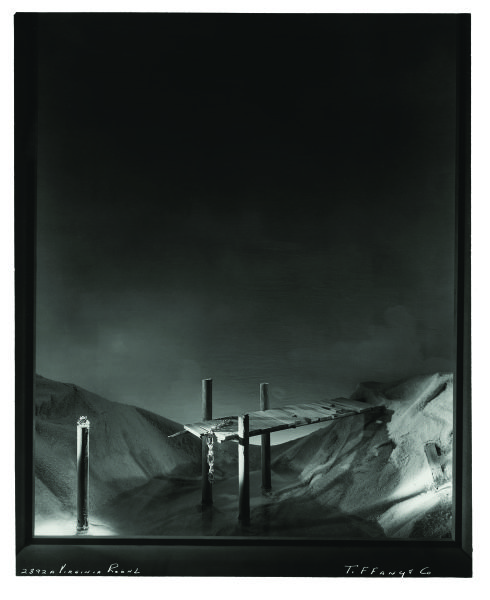

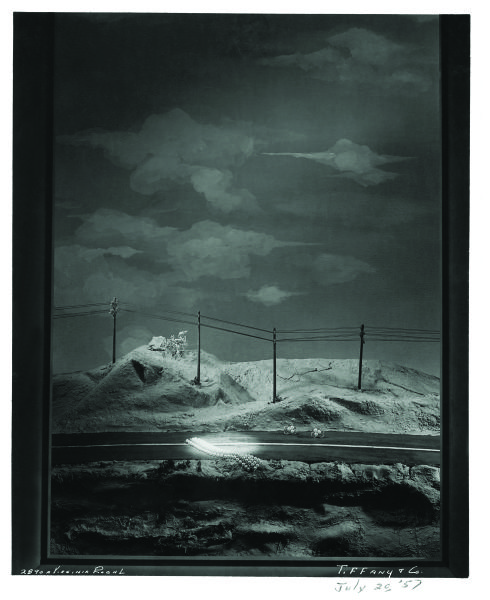

July 20: Landscapes

[ed note: this “ravine” and “bridge” looks like a broken dock to me. Indeed, that is the caption in the Obsever.]update: image via Tiffany & Co.

update: image via Tiffany & Co.

I’d asked Johns and Rauschenberg to make me some outdoor scenes. I said, “Make me a swamp, a ravine [above], a wishing well, a rock, and a highway [above].” I had some somber scenes in mind and painted dark skies as backgrounds. One window had trees growing out of a swamp. Another had a broken bridge jutting over a ravine. I used real water in these windows , with a circulating pump to keep it moving slightly. The well was a by a tree, one of Matson Jones’s famous bare trees. They made the rock out of painted papier-mache, and I set it on real dirt. The highway, divided by a white line, was bordered by telephone poles-a lonely stretch of road in the middle of nowhere.

There was jewelry in all five windows, casually tossed in the swamp, dangling precariously in the air off the bridge over the ravine, dangerously near the well, atop the rock, and laid across the highway. Not the safest of places for expensive trinkets, not the kind of scenes associated with Tiffany’s jewels. But diamonds look beautiful in dirt. [p. 84-6.]

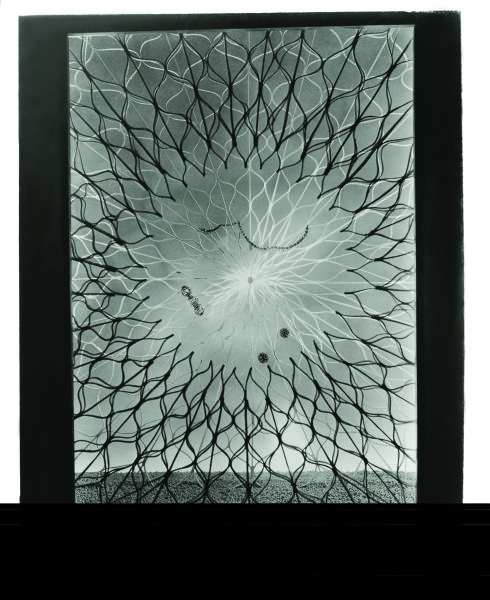

August 29: Webs

update: image via Tiffany & Co.

They made forms like webs, and the jewelry placed on them almost took the shape of insects. In one window the web became a trampoline, with the jewelry bouncing in the air over it. [p. 86]

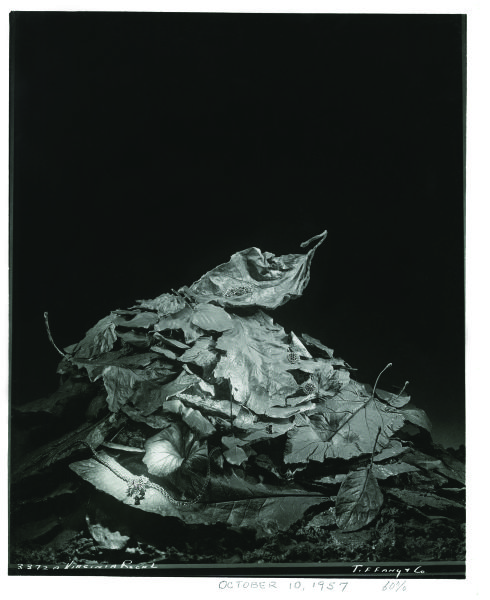

October 10: Piles of leaves and falling leaves

update: image via Tiffany & Co.

For the next windows, autumn windows, Rauschenberg and Johns made me plaster casts of leaves. [ed note: Richard Moore said they were real leaves, maybe there was both?] I had them falling gently through the windows, each falling leaf carrying a jewel, or swept into piles, with jewelry swept in, too. In one, the falling leaves had knocked over a glass, or at least that’s what I’d intended. People wanted to know why the glass was on its side. I told them people all over, why not a glass? [pp. 86-8.]

1958

September 8: Dimensional cutouts of birds

September 1958. That is months after both artists had their breakout shows at Castelli. There are more pictures of these windows somewhere, I feel like I’ve seen them. A 1959 NYT article says NYC window displays were often sold on to other cities. Maybe there are icy caves and cast plaster lemons and cabbage leaves to be found in the attics of retired midwestern window trimmers.

Previously: Melons and Pomegranates, Matson Jones Custom Display

Jasper Johns Blue Ceiling by Matson Jones

[A style note: I know it’s called Tiffany & Co. And that some people feel they’re all that for calling it Tiffany, as if Tiffany’s was just something you learned from a movie. But since Gene Moore called it Tiffany’s, I called it Tiffany’s. update: Except in the credits of the updated images, which, props to the firm.]