When I heard that Christopher DeLaurenti used body mics and a mini-disc-equipped vest to make his surreptitious recordings of orchestral intermissions, I was like, "Half the recording is probably the squeaks of his leather vest. What he's actually capturing isn't just music; it's his experience of listening."

As I read on in the NY Times article about his new CD, I was pleased to learn the "Seattle-based 'sound artist' [quotes? please, this isn't Seattle -ed.] and composer" agreed:

The recording itself became a performance, he said, because every movement of his body would alter the way the sound was captured. "I became entranced in doing it," he said.The illicit nature of the project not only informed the recording process, it provides the aural rhythm, a 6bpm directional bassline:

He honed a technique of often shifting his posture and moving around. "Most people are not observant and rarely look at one thing for longer than 10 seconds," he said.Any John Cage reference or influence is always welcome around these parts, of course, and the transformation of ambient sound into music is one of my personal favorites.

But Cage also had an interest in the transformed roles of peformer, composer, and audience. In a 1972 interview, he said:

...more and more in my performances, I try to bring about a situation in which there is no difference between the audience and the performers. And I'm not speaking of audience participation in something designed by the composer, but rather am I speaking of the music which arises through the activity of both performers and so-called audience. . .When a piece like 4'33" is ultimately peformed/composed/experienced in each listener's ears and head, does it still make sense to keep using an implicitly passive term like "audience"? Does it matter that DeLaurenti declares himself an artist, not just an audience member? Does it matter that he published his work? Or that he released a commercial recording?

DeLaurenti's project also reminds me of another artist of the experiential whose practice is also technically illegal: the videocam-wielding moviegoer Jon Routson.

Routson used to shoot video while he was in the movies, not to create a bootleg of the feature film--justifiably afraid of getting caught, Routson usually didn't even look through the viewfinder of his camera, which turned the secreen into a skewampus trapezoid--but to document the experience of watching a movie. Ambient, quotidian life became art; art was what the artist did--including sitting through three screenings of Mel Gibson's The Passion .

Looking back on how he developed his early studio practice, Bruce Nauman told an interviewer [pdf] that he wondered, "... what an artist does when left alone in the studio. My conclusion was that I was an artist and I was in the studio, then whatever I was doing in the studio must be art." And in the cases like DeLaurenti and Routson the studio is expendable.

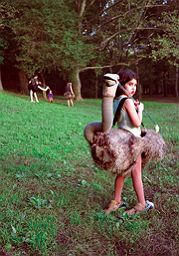

But artists like Vito Acconci, who made video art from his daily doings, and at-home dad/artist Guy Ben Ner, who transforms primary caregiving into production by enlisting his kids as characters and crew in his video works, have it easy.

But artists like Vito Acconci, who made video art from his daily doings, and at-home dad/artist Guy Ben Ner, who transforms primary caregiving into production by enlisting his kids as characters and crew in his video works, have it easy.

The two bootleg guys face a unique challenge because their experience involves consuming--and recording--someone else's intellectual property. The most remarkable thing about the Times' intermission article is how laid back almost all the orchestra spokesmen are about DeLaurenti's recording. Granted, no one's going to go ballistic to the Times in a culture feature, but it's like winning the Turner Prize compared to the draconian treatment that Routson faced.

Maryland criminalized videotaping in a movie theater while the Baltimore artist was still making his works. He moved production to New York for a while, but the film industry's aggressive campaign against 'piracy' and the subsequent changes to federal law ultimately forced him to abandon his series.

So all the world's a stage, and we are merely gloriously players. And playwrights. And composers. And artists. Except that large swaths of our production--our lives--are declared the exclusive property of the expensively counselled copyright and trademark industrial complex. All the world's a store, and we are merely consumers. Meanwhile the cameravans prowling our city streets are from Google. All the buildings on the Sunset Strip seems really quaint right about now.

The Concerts Found Onstage While Everyone Else Takes a Break [nyt]