Score one for the bloggers. In the face of an instant, last-minute, blog-fueled burst of attention, the Utah Department of Oil, Gas & Mines has extended the public comment period until Feb. 13 for Application to Permit Drilling #08-8853, which seeks to conduct test drilling for oil in the West Rozel Field, an underwater oil deposit in Great Salt Lake.

The proposed drill sites are a couple of miles away from Rozel Point, the site of Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty. After a heads up from the Friends of The Great Salt Lake, Smithson's widow and the executor of his estate, Nancy Holt, fired off email alerts to the art and media worlds, urging them to act "to save the beautiful, natural Utah environment around the Spiral Jetty from oil drilling."

I dutifully fired off my letter, expressing my grave concern for the fate of "the single most important work of art in the state." Apparently, at least a thousand other people around the world did, too, and in one day.

But something seems odd to me. What's the actual threat, where does it come from, what's the logical--and realistic--solution, and what do we know about what the artist himself would think about oil production nearby his masterpiece? Holt's calling for protection of the Jetty's "beautiful, natural" surroundings doesn't exactly reflect the reality of the work. Likewise, Lynne deFreitag, the FOGSL chairwoman who raises the specter of "offshore equipment [that] could cause noise and visual impairment in a relatively pristine area."

Now the National Trust of Historical Preservation has weighed in, calling the Spiral Jetty "a significant cultural site from the recent past, merging art, the environment, and the landscape."

Rozel Point may be beautiful, but it is not pristine, and it's not natural. And oil drilling is no stranger to the area, either. By ignoring the specific industrial history of the Spiral Jetty and its site, these defenses, however well-meaning or much-needed, are incomplete and inaccurate at best, and misleading at worst.

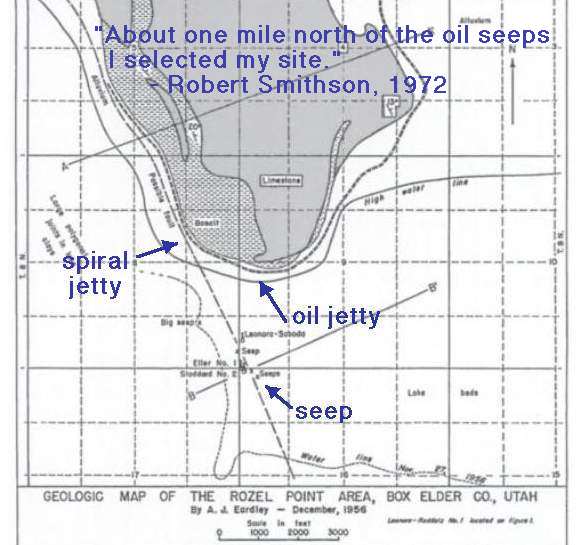

According to Smithson's own accounts of the project, oil and oil production are inextricably linked to the Spiral Jettyand the reasons Smithson chose to build it at Rozel Point. A choice based on, among other resources, his consultation of his copy of the 1963 Utah Geological & Mineral Survey map titled, "Oil Seeps of Rozel Point." [image: via Ron Graziani's 2004 book, Robert Smithson and the American Landscape]

As he explained in a 1972 interview with Paul Cummings:

You might say my early preoccupation with the early civilizations of the West was a kind of a fascination with the coming and going of things.... And I became interested in kind of low profile landscapes, the quarry or the mining area which we call an entropic landscape, a kind of backwater or fringe area...He continued, rather romantically, explaining the landscape of debris from decades of failed oil expeditions:

An expanse of salt flats bordered the lake, and caught in its sediment were countless bits of wreckage. The mere sight of the trapped fragments of junk and waste transported one into a world of modern pre-history...[In 2005, the state decided to clear out all these ruins and debris using money from the Division of Oil, Gas & Mining's "orphan well" fund. "Within 16 days," brags the Utah Geological Survey website, "a total of eighteen 40- cubic-yard dumpsters full of junk were hauled away! Only some old wood pilings and historic stone building foundations were left behind...So, if you have ventured to the area before, either to see Rozel Point or Spiral Jetty, you may not recognize it when you return!" [emphasis added]Two dilapidated shacks looked over a tired group of oil rigs. A series of seeps of heavy black oil more like asphalt occur just south or Rozel Point. For forty or more years people have tried to get oil out of this natural tar pool. Pumps coated with black stickiness ruted in the corrosive salt air. A hut mounted on pilings could have been the habitation of "the missing link." A great pleasure arose from seeing all those incoherent structures. This site gave evidence of a succession of man-made systems mired in abandoned hopes.

About one mile north of the oil seeps I selected my site.

Interesting that to the state, wood pilings and stone foundations are "historic," but the metal/industrial elements were "junk." It's a diametrically opposite view from the artist's own.

Even though the "Diluvian" ruins of failed oil drilling were central to the choice of Rozel Point, and even though he built his own Jetty right next to an abandoned oil drilling jetty, the industrial nature of the site was largely omitted from critical discussion of the Spiral Jetty for decades while it lay submerged and unvisited.

During the 2004 retrospective at the Whitney, Todd Gibson noticed how Smithson largely excluded the surroundings from the Spiral Jetty film:

This is interesting because Smithson could just as easily have chosen to place Spiral Jetty within the context of the industrial landscape in which he built it. At two points during the film, viewers get a passing, background glimpse of the oil-drilling jetty situated less than half a mile to the east. You have to be watching for it to see it, the shots are so quick. (See the satellite photo at right for an indication of how close these two jetties are--and by how much the industrial jetty dwarfs Smithson's work.)It's too late, and this is too long already, so I'll have to look into the questions of the current oil drilling situation in another post. Meanwhile, don't forget to write your letter of support for the Jetty! Demand that the state restore the 18 trailerloads of pumps and junk immediately!I was surprised by these two shots in the film because they both show not just the oil drilling jetty that remains at the site today, but they also clearly show a giant drilling derrick at the end of the jetty that is no longer there. The site was even more clearly a working industrial landscape at the time Smithson built his piece than it is today, but Smithson chose not to highlight that fact in the film--even though his Non-site works had explored the concept of the industrial, entropic landscape a few years before.

It's only been in the last few years, since Spiral Jetty reemerged from the water and people started visiting the site again, that discussion of this aspect of the work has arisen.