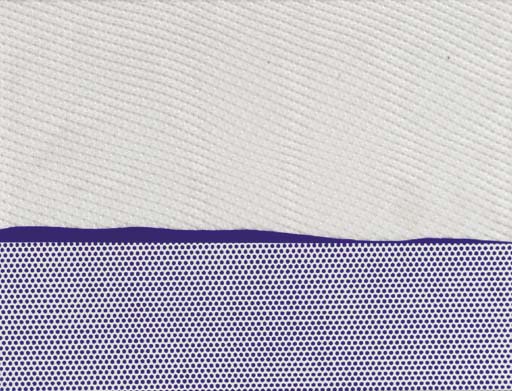

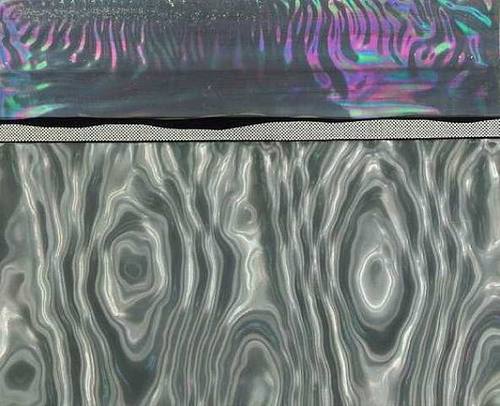

Seascape I, 1964, screenprint on Rowlux, ed. 200, from New York Ten portfolio [via]

You know how you just think you'll blog about one thing, and then you want to get a little context, so you dig a bit, and then a bit more, and a bit more, and.. anyway, even though I rather obsessively collected out a bunch of his source comic books in the early 1990's, I haven't been a close follower of Lichtenstein's work. Or rather, I think I've been lulled into a sense of familiarity by Lichtenstein's almost immediate recognizability, and I never paid too much attention to when he made what and why or how. It just was.

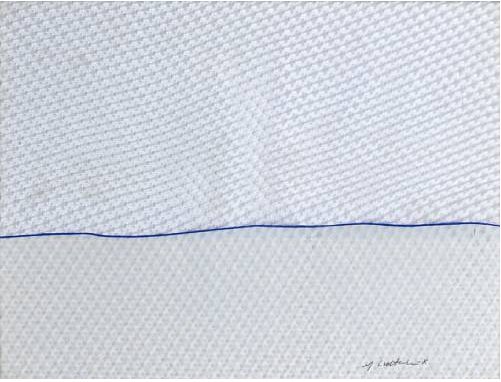

Seascape I, 1964, printer's proof, Rowlux, different horizon, no Benday [via]

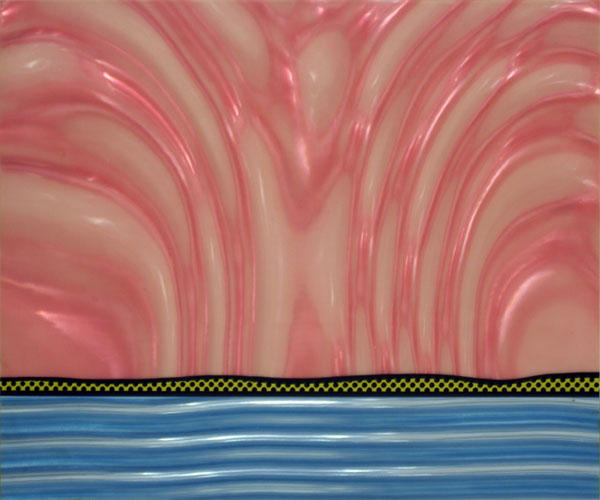

Which is why these early landscapes and seascapes are so fascinating. They're so odd, so resolutely unfamiliar, almost unrecognizable as Lichtensteins, and yet they're from 1964-68, a period when Lichtenstein's career specifically and Pop Art generally were both gaining global recognition. They seem like experiments, avenues of persistent research. They account for some milestones: Lichtenstein's first use of his own subject matter, inclusion in his first museum show. They have clear--or at least compellingly arguable--influence on later, major work. But they still somehow feel atypical, marginal, minor, dead-ends, even failed. But are they? Could they just be underseen or underappreciated? Undervalued by the market because they don't "look" like Lichtensteins [yet]?

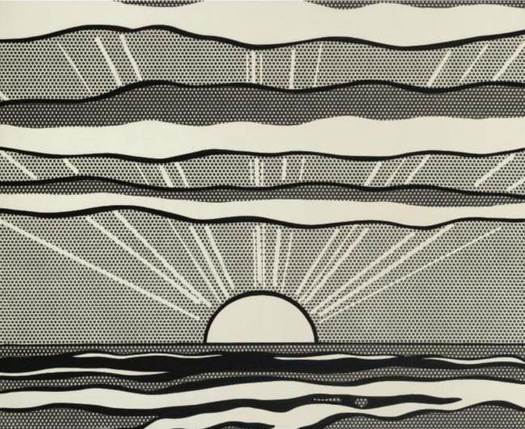

Black and White Sunrise, 1964, oil on magna on canvas [via]

According to the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation's official chronology, the artist began making landscapes in early 1964. Some were painted rather spectacularly, like the black and white sunrise [above]. And with others:

And near the end of '64, there's this [images top]:

Begins to incorporate plastic, Plexiglas, and metal into some of his landscapes.

Rosa Esman begins Tanglewood Press with the portfolio, New York Ten which includes Seascape, 1964, a color screenprint on clear Rowlux by R.L.Rowlux is a wavy, prismatic plastic sheeting material which Lichtenstein apparently discovered at a novelty store. Its moire pattern can simulate reflections on water. [Hmm, novelty shop? The Rowland brothers were trying to market Rowlux for use in highway signs, and according to Ron Abbe's 1976 paper, "Experiment with Rowlux," Salvador Dali was the first artist to use the material, in 1962. Dali decked some models out in Rowlux collages for a "couture" show in 1965. What a mess.]

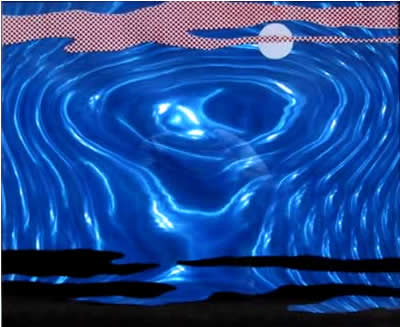

Moonscape, 1965, silkscreen on Rowlux, ed. 200 [image]

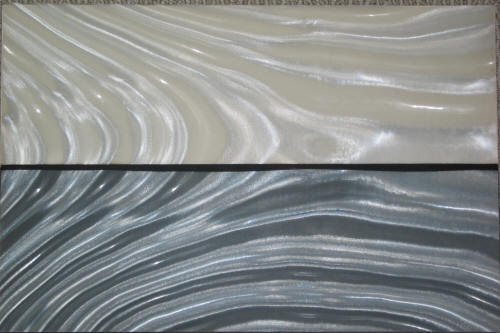

In 1965, Lichtenstein made painting collages using Rowlux and other materials. The dealer Mark Borghi, which is selling Littoral [below], lists some more. Littoral was purchased from Castelli by Larry Aldrich and made its way to his museum, which apparently deaccessioned it at some point.

Littoral, 1965, Metalized polyester foil, aluminum and magna on board, [via]

1965 was also when Lichtenstein began experimenting with adding backlights and motors to his Rowlux painting collages, making them a hybrid of kinetic art, light art, and moving picture. Examples of these Electric Seascapes were included in the artist's one-man show at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1967.

Electric Seascape #1, 1966, Rowlux, paper, light, electric motor, formerly Collection Guggenheim Museum [via]

I think two statements Lichtenstein made about his explosion paintings, which he began around the same time, are also relevant to these landscapes. First, from his interview with John Coplans for the 1967 Pasadena show catalogue, there's a conscious technical distancing from painting: "I wanted the subject matter to be opposite to the removed and deliberate painting techniques." And in Aspen No. 3, published in December 1966:

Explosions give me a perfect opportunity to do a completely abstract painting which seems, on the surface to he realistic.

Electric Seascape #2, 1966, Rowlux, wood, light, motor [via]

While Moonscape is pretty strongly representational, many of these landscapes are as abstracted as Rothkos or Sugimoto photographs. Sometimes the only representational element is the hint of a Benday horizon contour--or the light playing on rippling water, which is, of course, an illusion intrinsic to the material itself.

Landscape 2, 1967, silkscreen on Rowlux overlay, ed. 100 [via]

Lichtenstein kept on making these Rowlux collages and editions at least through 1967, when they were reduced to almost nothing but a horizon line. The two 1967 works here were from Ten Landscapes, Lichtenstein's first solo print portfolio, published by Castelli.

Landscape 5, 1967, silkscreen on Rowlux on board, ed. 100 [via]

When they were made, then, Lichtenstein's hotness and Castelli's marketing magic helped these trippy landscapes into major collections like the Guggenheim's and Larry Aldrich's. They were what's available, and they got snapped up. And then at some point, those institutions decided they were expendable, or outside the Lichtenstein narrative, and they ended up back out into the market. Assuming it's still available, Borghi's Littoral has been on the market for at least two years.

Besides their intentional distance from the painting process--a major concern of almost all Lichtenstein's work--these shimmery landscapes and seascapes are almost nakedly direct explorations of the characteristics of light, sight and visual perception. The play of light and reflectivity would become significant subjects for Lichtenstein going forward--his first painting of a mirror [below] was made in 1969. In 2000, an entire show of Lichtenstein's light-related works, titled "Reflection/Reflessi," was organized in Rome. The inclusion of Electric Seascape #1 only highlights the extent of Lichtenstein's investigations.

Mirror #1, 1969, oil on magna on canvas, [via]

But these landscapes also related directly to another series of unusual works, the ones that started me on this whole researching jag: Lichtenstein's only films. Which are coming soon to a blog near you.