Robert Rauschenberg's massive 1970 silk screen edition, Currents sure is hard to miss. And not just because it's 18 meters long.

MoMA's copy from the edition [of just six] has been wrapped around the corner of the second floor galleries for a while now. Which may have helped coax Peter Freeman into bringing out another of the screenprints last week for Art Basel.

But it's also at the end of the Rauschenberg's segment in Emile de Antonio's documentary, Painters Painting [above], which I rewatched recently. Bob unfurls it with a slightly soused, earnestly glib voiceover about how, even though there's so much information packed into a daily newspaper, most people don't read it. But if someone spends $15,000 on the info, the artist can get him to pay attention. Or at least not wrap the fish in it and throw it out.

Which is ironic, I guess, because I've found that the size and visual uniformity has caused me to stroll by Currents without ever even slowing down. I register it as reworked newspaper content, on a giant roll, just like the real newspaper itself--but I don't slow down to look closely. I mean, really, at that scale, how much of my time does Rauschenberg really think he's gonna get?

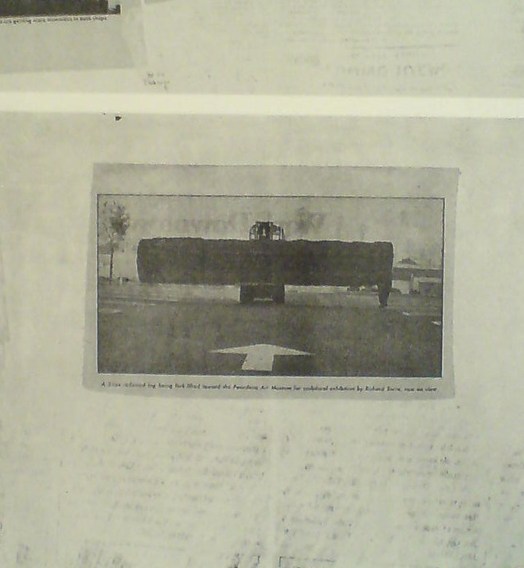

So maybe it was because I'd just run into Richard Serra moments before in the atrium, or because I came at the work head-on this time, instead of from the side. But I'd never noticed, for example, that there is a news photo of a frontloader bringing a massive fir tree trunk to the Pasadena Art Museum for Serra's 1970 work, Sawing: Base Plate Template (Twelve Fir Trees)

Above it and to the right, I'd swear that row of tract houses is a Dan Graham photo.

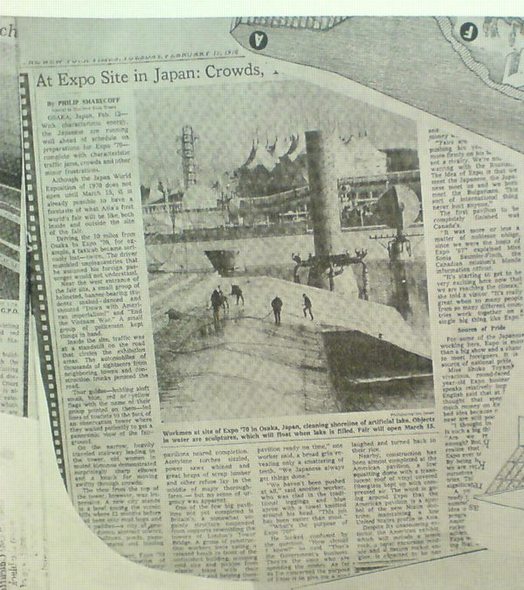

And hey, there's a story about construction progress on Expo 70 in Osaka, where E.A.T., the collaborative Rauschenberg founded with Billy Kluver, was creating the Pepsi Pavilion, and where Rauschenberg was still thinking he'd show his own work, a plexiglass cubeful of bubbling drillers' mud called Mud-Muse, which he'd developed with Teledyne for LACMA's Art & Technology show and the US Pavilion.

If I can spot these now-obvious contemporary art references in Currents, what else must be lurking in there? Was incorporating other artists' images Rauschenberg's way of tipping his hat to artists and work he liked, or was he assimilating and subsuming it in his own, sprawling scroll? Was he engaging in a dialogue with the Conceptual and post-minimalist kids coming up or putting them in their place? Or trying to put himself in theirs?

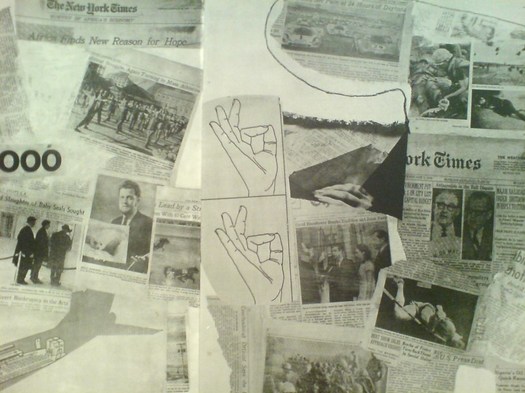

The most intriguing references now, though, turn out to be a little trickier. There are multiple instances of diagrams showing hands throwing the OK sign which remind me of nothing so much as the sign language woodblocks used in the prints at Jasper Johns' latest show at Marks.

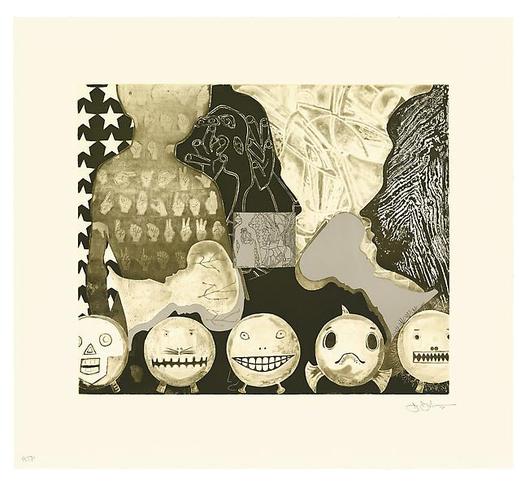

Shrinky Dink 4, 2011, intaglio print, image via

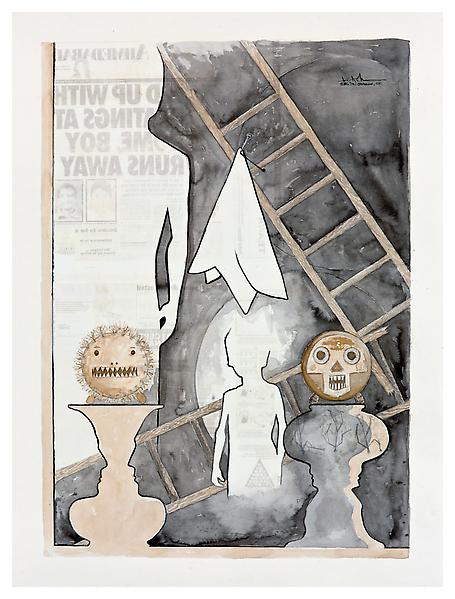

I remember thinking immediately of Rauschenberg when I saw the mirrored newspaper transfer appearing in the upper left of this Johns drawing, Untitled, 2010.

Rauschenberg began using the technique in the mid-60s, and it's all over Currents. Remind me again how long MoMA's had their print on view?