Andrew pulls a great quote from this 1969 New York Magazine article by Rosalind Constable about buying the new-fangled, dematerialized art. But it's the section right before it that caught my eye.

Constable's writing about earthworks, particularly Walter de Maria, is a good reminder of the Conceptual context from which these works emerged:

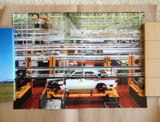

Walter de Maria is generally conceded to have been the first artist to have used the desert for his canvas, and in so doing, to have reversed the usual art process: the work itself is ephemeral--or inaccessible--and the photograph becomes the art.

There's like five kinds of quaint here, including the immediate invocation of the traditional metaphor of the artist and his canvas. There's the conflation of ephemerality and inaccessibility, even as notions of remoteness and inaccessibility disappear. Site becomes as irrelevant as experiencing the work in person. Knowledge of the work is derived from seeing a photo, or from hearing or reading a description. The apparent novelty of a site-specific artwork in the remote desert is surpassed only by the idea that a photograph could be a work of art.

But what really gets me is the discussion of Smithson.

Robert Smithson is known as an earthworker (Heizer prefers the terms "landforms" or "exteriorization," and Oppenheim prefers "terrestrial art"), but other earthworkers would exclude him. Smithson is currently showing his latest collection of rocks at the Dwan Gallery, and it is precisely because he brings them into a gallery ambiance, rather than leaving htem where he found them, that they disown him.This seems like a pretty hefty oversimplification of the emergence of Land Art. In the battle for linguistic dominance, "earthworks" was Smithson's coinage; other artists could reject the term, but it seems unlikely they'd claim Smithson wasn't an "earthworker." It also ignores the broader critical round-up by folks like Willoughby Sharp, who'd curated a foundational "Land Art" show the year before. And the "Earthworks" group show at Dwan that preceded the Smithson non-sites that were the subject of Constable's sources' scorn.

Still, it feels directionally accurate, in that from almost the beginning, the art world discourse of earthworks has generally privileged the convenient and collectible--including mere photographs--over the physical realities of the works.

Though this has changed in the last 15 or so years, with the emergence of a contemporary Grand Tour, the lingering critical effects of this devaluation of site can still be felt.