In the Spring of 1991, I was about nine months out of school, and six months into a new job. After striking up a conversation with a documentary film crew from NHK at Tennessee Mountain in SoHo, I'd bailed on a hard-won banking job right before my analyst training started. I began doing research and pitching and packaging projects. A few months in, I began working on producing a multi-part documentary on the history of the oil industry based on Daniel Yergin's book, The Prize. I went off by myself to Houston to try and persuade oil company executives, particularly Aramco, Saudi Arabia's US operation, to participate. I'd put in some calls and send out some faxes, then basically wait by my hotel phone, hoping a PR or some other contact would call me back. It was at once heady and exhilarating, ridiculously inefficient, frustrating and boring, and ultimately pointless.

Before heading back to Houston one week, a friend in New York suggested I use some of my downtime to find the Rothko Chapel. I knew Rothko from sitting in on the modern/contemporary art history class my last semester, and from MoMA of course, but I hadn't heard of any Chapel.

[via]

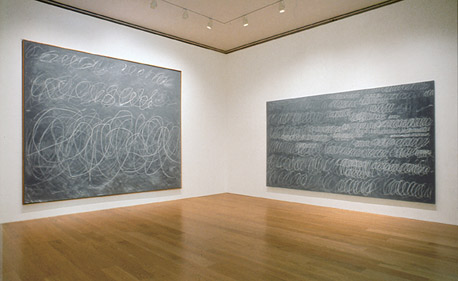

The concierge at the hotel didn't know it either, but she gave me directions to Sul Ross, which turned out to be very close by [I was staying at the Wyndham.] With no idea what to look for, and not seeing anything particularly chapel-like, I circled around the bungalow neighborhood in vain, until I came upon a long, low, windowless, warehouse-shaped, grey clapboard building. There was no sign. Looking into the glass entry, though, I saw something else from my contemporary art class: a Cy Twombly chalkboard painting.

it was Untitled, 1967, on the right. image: menil.org]

If they had a Twombly, I figured, these people might know where the Rothko Chapel is. So I pulled over and went inside to ask directions. A charming lady with her white-hair in a bun at the desk happily pointed me back down the street. And then I asked if that was, in fact, a Twombly painting over there. Yes. Would she mind if I went to take a look. Of course.

As I was standing there, marking the many differences between an actual painting and a slide lecture, a tall, elderly man came out of a set of doors to my left, and joined me in looking. I looked at him briefly, and then the painting. And then back at him, because he was looking unexpectedly familiar.

"Excuse me, but are you Cy Twombly?" I asked.

"Yes," came the reply.

I rambled something about really liking his work, and studying it in school, even though my emphasis was Italian Renaissance, and this being the first time I'd seen one in person while he smiled and nodded and said thanks. He asked where I'd gone to school. And if I had seen other pieces in the museum that I'd liked?

Which stumped me, because I somehow still hadn't realized I was in a museum. I was a little embarrassed and said I'd been looking for the Rothko Chapel, saw his painting through the window, and stopped to ask directions. Twombly, amused, maybe pleased, said well, it's really not like the typical museum, and then he suggested I really should see it, I'd enjoy it.

I said I would, and thanked him, and then he left. Some time later, when the catalogue for Walter Hopps' show of Rauschenberg in the 50's came out, I noticed the dates in a footnote and realized that Twombly had been at the Menil that day to be interviewed. So maybe, I thought, he had the formative art experiences of youth on his mind when he gave me one of mine.

The experience of meeting Twombly in front of his painting completely changed my understanding of artists and art and artmaking. Art was not just history; it was now. And it was being made by people you could meet and talk to. If you happened to bumble along in the most implausible way and fall in with some of the most important and visionary and generous people in the art world, like Dominique de Menil, but still. It was in the realm of the possible. At least until yesterday.

I was going to write how meeting Twombly turned me inexorably toward art made by living artists, even as the impetus for writing is the artist's death. I'd thought about this after Leo Steinberg died; I'd met both him and Dominique that week, too. Maybe it's being involved with art of our time--of my time--that came into focus that day. The artists whose work we admire, the people whose ideas influence us, are around for a while, and we can engage them. And then at some point, they're gone, and we're left with just their works and their words. And with our own experiences and memories.