What's the opposite of writer's block, the thing where you have so much damn good stuff to write about, you're paralyzed into inaction? Because that's what I've got, and August vacation voids or not, I just can't help it; I'm gonna blog it all and let Google sort it out.

For example, for all the dome- and Expo-loving going on around here, you'd think by now I would have gotten my hands on a copy of Jack Masey and Conway Lloyd Morgan's 2008 book, Cold War Confrontations: US Exhibitions and Their Role in the Cultural Cold War, but no.

For example, for all the dome- and Expo-loving going on around here, you'd think by now I would have gotten my hands on a copy of Jack Masey and Conway Lloyd Morgan's 2008 book, Cold War Confrontations: US Exhibitions and Their Role in the Cultural Cold War, but no.

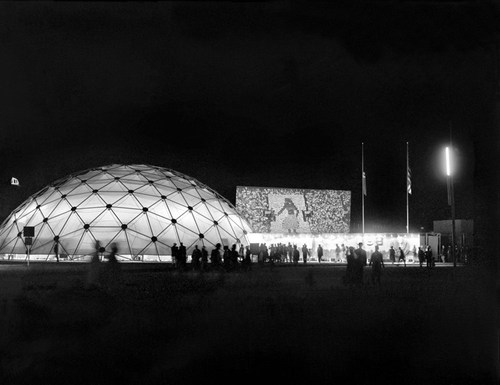

As the longtime design director for the US Information Agency, Jack Masey was basically the client, or the producer, of the expo-related architecture, art, media, domes, pavilions, exhibitions, and propaganda that folks like Buckminster Fuller, Shoji Sadao, the Eameses, and George Nelson became famous for.

Cold War Confrontations is a fantastically surfable book, a thick, highly visual memoir of the USIA's greatest hits. It's based on the premise that the structured, official propaganda pageants of world expos, culture exchanges and trade shows, played pivotal roles in the course of post-war world history:

At Expos, however, the teams are not playing games; rather, they competed by presenting to the world examples of a nation's best architecture, technology, arts, crafts, manufacturing, and performing arts. And in so doing, they sometimes, somehow, change the world. [p. 110]

There were many people who believe[d] that to be true. I sort of want it to be true, at least in the same sense that I'd rather see street gangs settle their differences by breakdancing instead of drive-by shootings. Maybe it's better to see these expos as reflections of the cultures that produced them, or of their aspirations. Because the views expressed therein do not, it turns out, necessarily represent the opinions of the United States of America as a whole, or of their elected representatives and/or government officials.

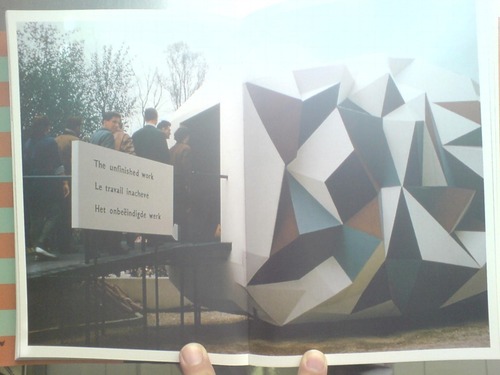

Case in point: The "Unfinished Business" pavilion, designed by Leo Lionni [!] for the 1958 Brussels World Expo. Holy Smokes, people.

Masey tells a longer version of the story in the book, but here's a condensed version: in 1956, a team that included Boston ICA director James Plaut consulted with MIT economist Walt Rostow on the contents of the official US pavilion, which was being designed by Edward Durrell Stone. The idea was to emphasize the US's people and cultural accomplishments. Rostow's team also called on the US to be frank and self-critical in recognizing its "unfinished business," by which they meant "soil erosion, urban decay, and race relations."

Somehow, though the giant, donut-shaped pavilion had room for a Vogue fashion show on water; a proto-Pop, pseudo-combine street sign streetscape; and a giant, aerial photomural of Manhattan installed in a half-pipe [WTF!? I don't know! We'll come back to it!]; there wasn't room to "address 'the Negro Problem.'" And so somehow [?] Henry Luce's Fortune magazine became the State Department's partner/sponsor of a smaller garden pavilion devoted to "Unfinished Business," and the magazine's creative director Leo Lionni designed it.

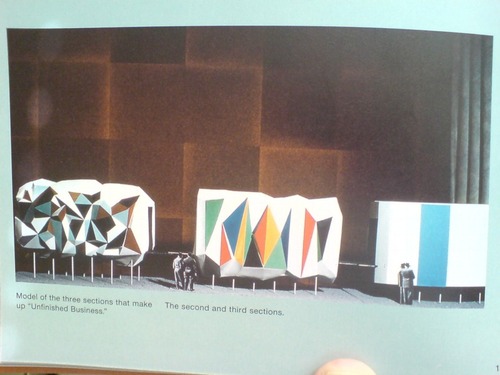

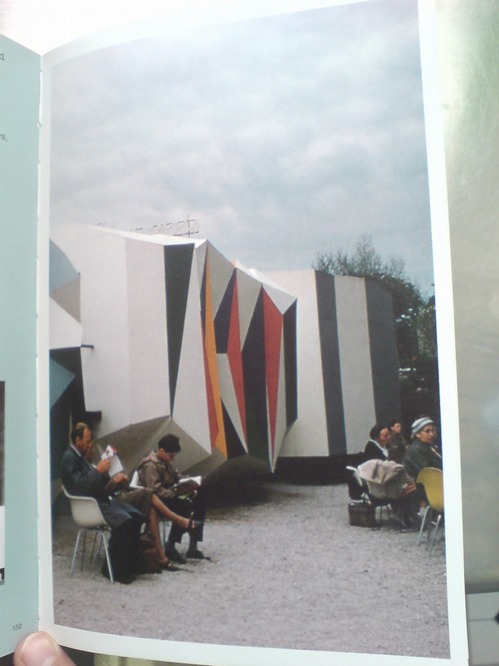

That's the model above, and it looks pretty damn close to the real thing. Lionni conceived of three linked, raised pavilions, each about six meters long, as a frankly allegorical timeline, in which America's problems get literally smoothed out. Or as Masey put it, "the content of the interior was also to be conveyed through the exterior." Which means that the somber, "chaotic crystal" of the past had already given way to the much brighter, Family of Man-colored present. A little more ironing and the square, orderly, utopian future was just steps away. That was the concept, anyway, but that's not exactly how it turned out.

[to be continued in the morning]

Buy Cold War Confrontations: US Exhibitions and Their Role in the Cultural Cold War on Amazon [amazon]