I've been annoyed for six weeks now by Laura Gilbert's op-ed in The Art Newspaper which argues, rather speciously, that "'appropriation'" [her scare quotes] is somehow a less "savvy" artistic practice than licensing images or seeking permission. She frames this as somehow "rarely reported," as if there's a taboo in the art world about acknowledging that some highly successful artists who have been accused of copyright infringement find the process annoying and expensive, and thus seek to avoid it going forward. This is certainly true, but such burdens could just as easily be used to argue, as some TAN commenters have, that the copyright litigation system is unwieldy and favors the big and powerful. [The examples of happy happy licensing Gilbert cites--Koons & Marvel; Warhol & Disney--support this.]

But whatever, I decided way back when the Cariou v. Prince complaint surfaced that I wasn't going to go tit for tat on every column or blog post concern trolling about copyright infringement.

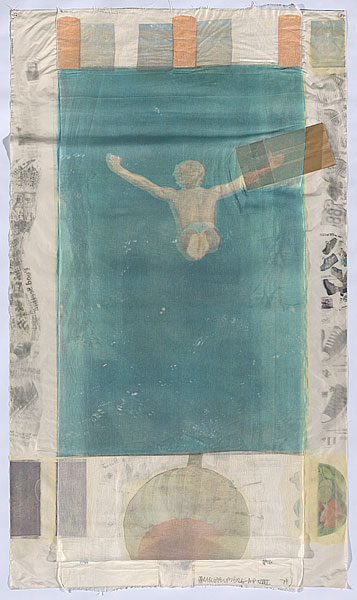

Rauschenberg's Pull (Hoarfrost Series), 1974, 8x4 feet, offset and silkscreen

on fabric, silk, and cheesecloth collage and paper bags, ed. 29 plus a bunch of proofs, image: nga.gov.au

What I will do, though, is confess that for all the soaking I've been doing in appropriation, I had never heard of the case Gilbert discussed at the greatest length: when Robert Rauschenberg was sued for using an image from a magazine ad in one of his collages by the photographer who took it, Morton Beebe.

San Francisco photographer Morton Beebe only discovered that Robert Rauschenberg had used two of his photographs in the 1974 print Pull when his friends, artists Christo and Jean-Claude, were looking at his portfolio. Christo pointed to the photograph Mexico Diver and said: "My God, is that yours or Rauschenberg's? Have you seen Time magazine this week?"I am quoting Gilbert's entire account of the case here because it sounds quite compelling and authoritative. But it is also biased--it's based entirely on Beebe's version of the claim and the settlement. And after investigating the original court documents, it's clear that Beebe's take leaves out key details and facts that could significantly affect how the case is perceived, and what it means.Beebe got hold of the magazine and saw in a feature about Rauschenberg that he had not only used Mexico Diver but also his photograph of a native New Guinean repeated across the top of the print. Both pictures were part of a series Beebe had shot for an advertisement for Nikon cameras that had appeared in 17 magazines.

Beebe sued. Rauschenberg's printer testified that the artist had showed him the Nikon ad and said: "I'll just lift it."

Rauschenberg settled, paid the photographer's legal fees and gave him a numbered print of Pull. He promised that whenever the image appeared in print Beebe would be acknowledged. Later, when Beebe discovered another unauthorised use of Mexico Diver, Rauschenberg gave him another print of Pull, which Beebe sold for $13,000.

Beebe points out that potentially high legal fees makes photographers reluctant to sue (in the US litigants typically bear their own costs). After the suit settled, in 1980, Rauschenberg shifted to using his own photographs exclusively for the next 28 years if his life, according to the Guggenheim Museum and others.

There's no doubt that Rauschenberg used Beebe's image without permission, nor is there any uncertainty that Beebe felt wronged by the far more famous artist's action. It's also the case that Rauschenberg insisted, even after settling with Beebe, that his collage process was fair use, and that it resulted in entirely new work. If for no other reason, Beebe v. Rauschenberg should be better known because it embodies these emotional, economic, and power complexities so concisely.

Ultimately, though, I think the case does not support the anti-appropriation position that Beebe and Gilbert are promoting. [As recently as 2010, Beebe used his Rauschenberg complaint to lobby the White House (pdf) to strengthen IP laws "to better protect the creative community from piracy even from our fellow artists."] I'll get to that in the next post[s].

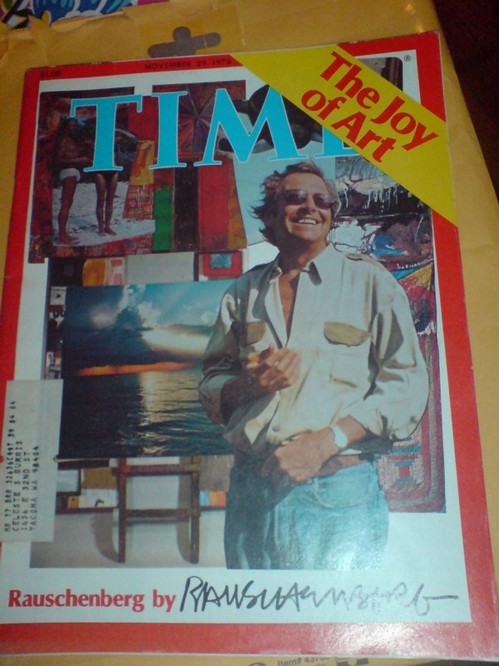

The other thing that's amazing and feels important about Beebe v. Rauschenberg is the similarity--which Gilbert surely caught onto as well--between Rauschenberg's appropriations and Prince's. I mean, seriously, people, Rauschenberg had made Pull from a Nikon ad in 1974, three years before Richard Prince rephotographed his first magazine ad at all--and six years before he rephotographed his first Marlboro cowboys. And while Prince was working in the bowels of Time Magazine making tear sheets, Rauschenberg was designing his own Time cover--and putting a little registered copyright symbol in the corner.

No Longer Appropriate? by Laura Gilbert [theartnewspaper]

One of the few articles to discuss Beebe v. Rauschenberg, Gay Morris's 1981 Artnet article, "When Artists Use Photographs: Is it fair use, legitimate transformation, or rip off?", is excerpted in the 2007 textbook, Law, Ethics, & The Visual Arts