A couple of commentators crystallize what is becoming the conventional wisdom about Wade Guyton's Instagram provocation last month, a few days before one of his paintings headlined a heavily hyped sale at Christie's. It's the idea, first expressed by a giddy Jerry Saltz, that Guyton is trying "to tank his own market by flooding it with confusing real-fake product."

Marion Maneker expressed concern that the Guyton's "threat" to create "a whole series of works from the previously unique printing of an image file" had backfired, and if we were all obsessed with his market now instead of his work, it's basically Wade's fault. From Art Market Monitor:

It's hard to tell whether Wade Guyton is inadvertently steering the conversation away from his art and toward his market or whether the artist has simply fallen prey to the Barbra Streisand effect where the more one tries to deflect attention to an event, the greater the interest.I just don't buy it.

As Guyton's own Instagram photo above showed, the Times [and Christie's themselves] had already made him the poster child for anxiety marketing for a auction that was actually full of guarantees and third-party pre-bids. If Guyton really wanted to destabilize his market, he could just pull a Cady Noland and demand the auction house remove his name from a work. This did not happen. Instead he reaffirmed the central element of his practice: that his paintings are each machine-printed renderings of infinitely reproducible digital files, whose uniqueness derives from the circumstances of their production. And record resale prices continued apace.

[How uncontroversial was Guyton's backup copy situation? Christie's auctioneer Loic Gouzer made--and signed--his own batch and sold it as an edition of 10, with proceeds going to Leonardo diCaprio's favorite shark conservation charity.]

If it did anything, Guyton's Instagram posts served as public critique of the Auction Week hype. It was a way to align himself critically against the system of relentless commodification--and to inoculate his work against the charges of speculation and cynicism that are leveled against auction stars. Even while his work was jostling around in the center of the hypercapitalist scrum.

Perhaps it's not fair to blame Maneker for toeing Carol Vogel's NY Times line, but he did it again in the very next paragraph, about the art market's very next get-together. In her Art Basel roundup, Vogel made a lot of hay about Guyton giving each of five dealers "a black painting, all the same size and all made from the same disk." Guyton calls it "a way of talking about the repetitive experience of seeing similar artworks throughout a fair and embracing that aggressively by showing almost identical works."

Which is taken by Maneker to be the artist's "ploy" to "orchestrate his market" and emphasize the arbitrage-friendly chasm between the insider/primary vs speculator/secondary channels. Except that's exactly how almost every artist deals with auction spikes, as any art market monitor would know.

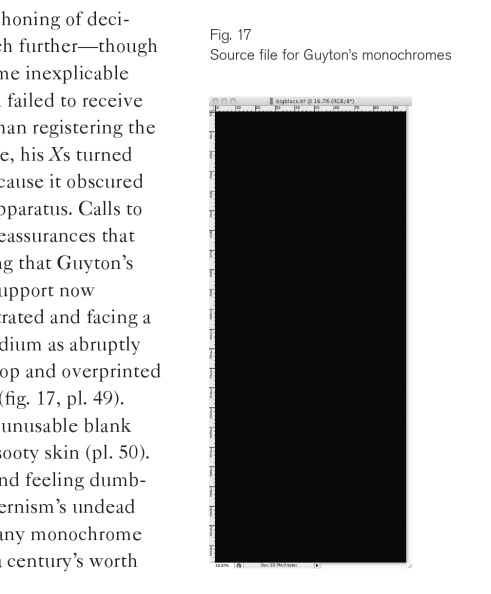

And there's another salient fact that's missing: Guyton makes all his black paintings from the same "disk," or as we call it nowadays, a "file." It's called bigblack.tif, and there's a screenshot of it in Scott Rothkopf's essay for the Whitney's 2012 OS exhibition catalogue.

installation view, 2008 Black Paintings show, Galerie Chantal Crousel

And he makes them in groups that at first seem indistinguishable. In 2007-8, he made three shows in a row, at Friedrich Petzel (NY), Chantal Crousel (Paris) and Portikus (Frankfurt) of nearly identical black paintings, installed identically. Just this spring, he recreated his entire 2008 show at Crousel, black plywood floor and all. Everything was the same. Except for the things that weren't.

installation view, 2014 Black Paintings show, Galerie Chantal Crousel

John Kelsey wrote in the 2010 Black Paintings catalogue:

What this work displays is the difference between sending information and receiving aesthetic objects in the gallery, or what happens when "black" moves from desktop to printer to museum, and whatever is lost along the way. The monochrome is a record of circulation. As it is copied and communicated, discrepancies are produced. And these are what now stand in for painting.Guyton: it's the little differences. And those are precisely what is lost when paintings are seen one at a time, in auction catalogues, art fair slideshows, and drifting by in infinite Instagram scrolls. Guyton's inky black paintings cast a harsh light on the impoverished experience of art-as-shoppertainment, of paintings decontextualized from the artist's practice and the flow in which they were conceived, and remerchandised as, well, merchandise. Paintings remain ruthlessly efficient units of exchange even though they're often no longer optimal units of aesthetic experience. That divergence marks what's lost when painting becomes nothing more than, as Ben Davis's timely quote of John Berger puts it, "a celebration of private property."

But it also marks a shift in artistic practice. Guyton's just one of many artists who create on the scale of the series, the installation, the context, the network, not the lone object. Rather than throw up his hands, or lalalala pretend it's not happening, Guyton's recent actions show him to be conscious of the art market's experiential crisis, and actively seeking out a way to engage or overcome it without throwing his paintings on the fire.