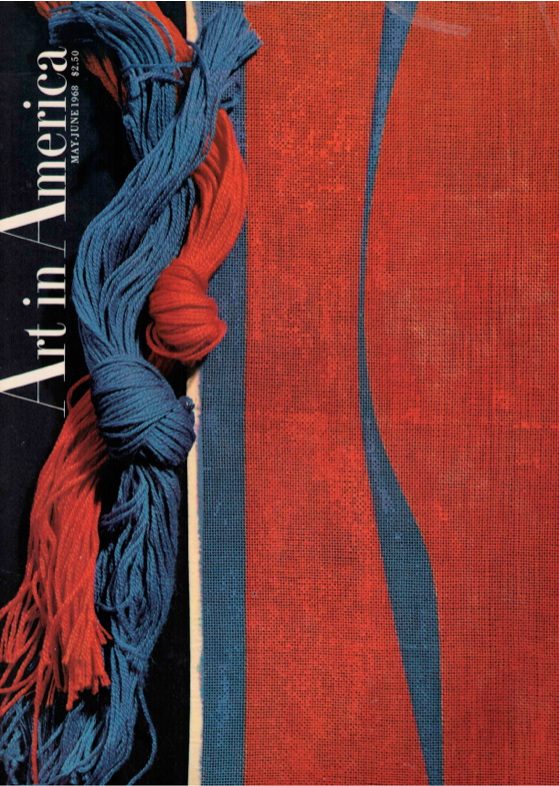

AiA May-June 1968 cover featuring Lorser Feitelson's Hi-Fi Speaker Cover

In 1968 Art in America commissioned thirteen artists to create needlework designs, which is really weird, and kind of great. I stumbled across the project a few months ago while studying up on Lorser Feitelson; the Los-Angeles-based surrealist-turned-hard-edge painter had talked about how, ironically, the needlework project turned him on to screenprinting, which gave him the smooth lines and flat surfaces painting never could.

Feitelson's contribution was a hi-fi speaker cover, which ended up on the cover of the magazine. It was the only image I could find online, and it made me want to see the rest. Because honestly, what could possibly be greater than abstract needlepoint hi-fi speaker covers? Oh, maybe Frank Stella throw pillows?

Frank Stella cushions, 15x15in., by Mrs. Leo Castelli

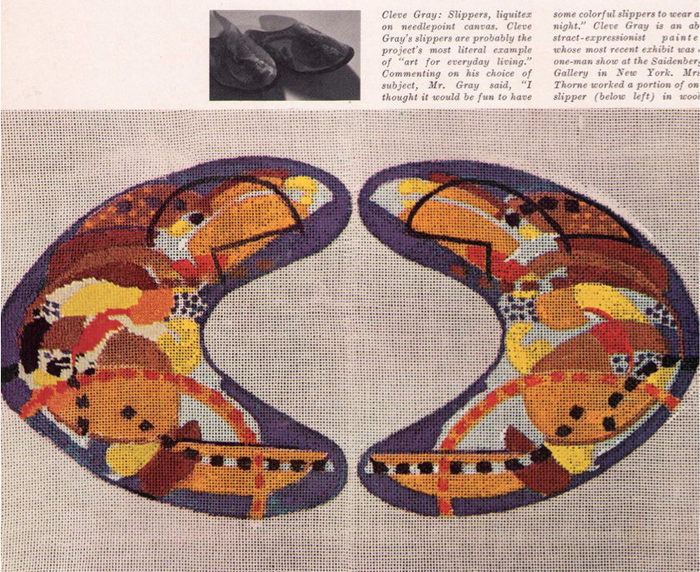

The artists selected by needlepoint evangelist Russell Lynes included folks like Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Stella, Gene Davis, Cleve Gray, Chryssa, Alfonso Ossorio, and Richard Anuszkiewicz. The rest, in descending order of interestingness to me, were George Ortman, Carol Summers, William Copley, Walter Murch, and Leonard Baskin.

Gene Davis Chair seat cover, 15x15in.

The whole project and context are pretty gloriously self-contained. Lynes laments contemporary artists' lack of interest in needlepoint, which he then acknowledges is an aesthetic backwater that has "unfortunately been considered a suitably genteel pastime only for otherwise unoccupied ladies." He's trying to pull the medium into the modern age, though, by taking designs from contemporary paintings, including Calder, Miro, and Mondrian. And he "interpreted (or rendered, if you prefer)" a Saul Steinberg illustration into a delightful seat cover. It all makes the hi-fi cover seem bleeding edge.

Little things keep jumping out at me throughout the article, which runs for 22 pages. Like the needlepoint-by-number painting kits that probably pushed Lynes over the edge in the first place:

the nadir of the craft, the "old master," partly worked by some poor soul and ready to have the background filled in by some poorer but more affluent soul.The way many designs are shown only partially completed, [It may have been a time thing.] and thus read as painting or printing on mesh. How the article makes a pitch for significance with its title, "The Mesh Canvas." And yet the needlepoint clothing submissions only grow in WTF-ness, from a vest and evening slippers, to a tie and a bikini. And the way Mrs. Leo Castelli walks away with the whole thing by stitching the best designs, the Stella and Lichtenstein throw pillows, her own damn poor, affluent self.

Roy Lichtenstein, Cushion, pen on canvas, 15x13.5in., executed by Mrs. Leo Castelli

Frankly, once I saw the entire project, I kind of lost interest; at least nothing made me want to learn needlepoint enough to make one. Or to try to ferret one out at Brimfield. There was apparently a show of the finished designs at FAR Gallery in New York, where "workable reproductions" were going to be available in limited editions. So maybe there were more than two Stella cushions or one Feitelson-covered hi-fi. But when's the last time you saw a hi-fi? If they made the transition from sketch to needlepoint object, I suspect basically none of these would survive the estate sale industry as tchotchkes, much less as art objects. If there were a set of Hepplewhite dining chairs with Gene Davis seat covers, they've surely been reupholstered by now.

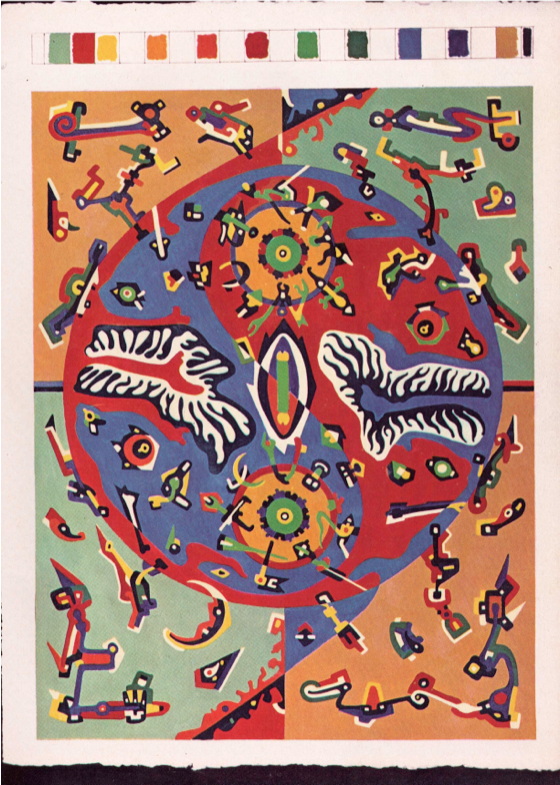

Alfonso Ossorio, Sketch for Fire Screen, 26x20in., propping your slipper-clad feet on a stool in front of this would be awesome.

Then I Googled Russell Lynes, to see why he even cared, and whoo-boy, because that was his job. The titles of his first four books were literally Highbrow, Lowbrow, Middlebrow (1949), Snobs (1950), Guests (1951), and The Tastemakers (1954), and in 1968 he'd just finished two decades as managing editor of Harper's magazine.

Bernard Perlin, Pillow, executed by George Platt and Russell Lynes, image: library.yale.edu

Oh, and his older brother was theatrical beefcake photographer George Platt Lynes, and together they needlepointed this fabulously gay pillow designed by Bernard Perlin, with George's initials formed out of muscly acrobats. And so maybe I'm completely wrong about the shelf life of these needlework pieces, because this pillow is now in the Beinecke.

image: library.yale.edu

It is one of three (well, four) embroidered objects in the collection. One is a Klee-inspired pin cushion George made as a Christmas present in 1944. And the other (two) is a pair of kid-sized fauteuils covered with Picasso designs stitched by Alice B. Toklas. They sat at the center of Stein & Toklas's rue Fleurus studio, and appear in many visitors' accounts. They were the first of many of Toklas's Picasso embroidery pieces, and the story of Stein maneuvering the artist into drawing the designs on the canvas is recounted in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas.

Though it's couched in terms of bringing needlework to contemporary artists, maybe Lynes' project was an attempt use needlework to bring new art to those who'd otherwise miss or resist it. Then seeing how folks like Toklas and Perlin and GPL perform and subvert needlework and make it their own, now that is interesting.

"The Mesh Canvas," by Russell Lynes, Art in America, May-June 1968 [dropbox greg.org, pdf, 28mb]

Previously: On Lorser Feitelson's Life Begins

Related: Juliet Clark on Toklas's embroidery and the chairs for The Steins Collect [sfmoma.org]