I watched the dedication ceremony Saturday, but I wanted to see the stained glass windows Kerry James Marshall made at the National Cathedral in person before writing about them.

It is, of course, impossible to consider the windows outside of their multiple contexts, including: the fleeting, classical Episcopalian spectacle of the dedication ceremony, whose explicit purpose was to inspire, and which has already floated away from the physical present now of the installation. The Cathedral and its institutional apparatus’ reckoning with the white supremacist symbolism literally built into it, over decades; the incremental recommendations and changes made in the wakes of multiple instances of anti-Black violence; the official committees formed amidst the activism of Black students at the Cathedral’s schools; and the seemingly relentless drumbeat of white Christianist fascism beyond the Cathedral’s walls.

Kerry James Marshall is surely aware of all this. He’s been making compelling art all his career for cathedrals built to exclude him. The National Cathedral knows all this, too, obviously; it’s what they chose him to do. In a way, or in part. What was the commission, and what, actually, did Marshall do?

As can be expected from the Windows Replacement Committee and the Textiles and Fine Art Committee, the commission was to replace one set of symbolic windows with a set of symbolic windows made by a fine artist. In this they have succeeded completely. But no one involved harbored any illusion that our culture, our country was going to One Great Black Artist our way out of the violent, inequitable mess we’re in. There are many accounts and reports and the statements of the principals themselves that convey their objectives, hopes, experiences, and expectations. I look at the windows themselves to see what Marshall has done, where they are, and what they’ll do, and try to interpolate some sense of them.

These are paintings, made by a painter. They are paintings on glass. Marshall thanked Andrew Goldkuhle, his stained glass collaborator, and the son of the fabricator of many of the Cathedral’s windows—but not the Confederate windows, which predated Dieter Goldkuhle’s arrival at the Cathedral by 13 years—but these were not outsourced. Details on the figures, the faces, and the signs were all painted by Marshall. I think he considered them and approached them as part of his main painting practice, and so should others.

Maybe the most significant aspect of the windows is their subject: protestors. If there is a lasting impact to be had from these windows, it may be the sanctification of protest and the right to redress in the symbolic religious center of the nation’s historic ruling class. That feels important, and an important marker of the commission’s own historical moment. It comes in the wake of the largest anti-racism, anti-police violence protests in generations, but they’re also unveiled at a moment where protest itself is threatened by institutional backlash and the corporate authoritarian consolidation of social media.

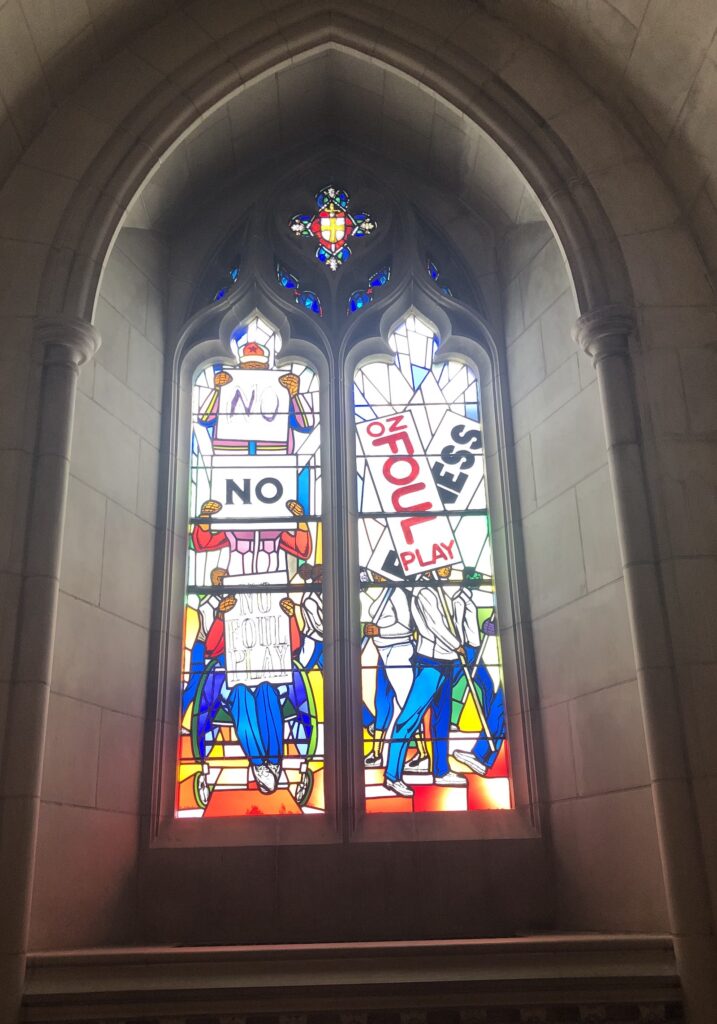

There are details in the windows that are worth noting. One pair of windows seem to depict one space, a streetscape of protestors holding signs. The other pair has a similar streetscape composition on one side, and a vertical stack of protestors, faces obscured by their signs, with a protestor in a wheelchair at the base. The top figure’s hands appear wrinkled, with a newsboy cap in the colors of the Pan-African flag; the middle figure may be wearing an 80s-vibe tracksuit. The three figures then seem to represent multiple generations, all engaging in protest.

Though known for his richly Black figures in historical-style paintings, the figures in the windows have a range of brown complexions—but there is also a purple face, and a green face. A/the green figure appears in both pairs of windows, giving continuity or resonance to the scenes. These could be multiple views of the same protest, or the echoes of history, or both. Purple and green feel like callouts to the “all lives matter” of the Bush era, when people’d claim they can’t be racist because they “don’t care if you’re, black, white, purple, or green.”

Then there is the most prominent feature of the windows: the protestors’ signs. Their messaging feels as stylized as their overtly handmade lettering. These are definitely not signs of this moment. But they also do not feel generic, but elemental, and above all, inarguable. FAIRNESS and NO FOUL PLAY feel like the kinds of things no one should have to march to achieve, because no one could reasonably oppose them. Which, I think, is Marshall’s point.

The posters also feel a little archaic to me. And they sent me searching for some historical sources Marshall might be referencing. The closest the specific language got me was to an NAACP report of the horrific lynching of two men, Robert McDaniels and Roosevelt Townes, who were wrongly accused of shooting a grocery clerk in Mississippi in 1937. They were dragged out of jail, tortured, and murdered by a white mob. The unwavering support by the entire local police and government, including prosecutors’ refusal to indict the widely known instigators of the mob, led the NAACP’s investigator to conclude that, “[O]nly the Federal government can safely intervene in such matters in support of justice and fair play.”

That contrast between the terror at hand and the restraint with which it could be safely called out reminded me of an image I’d seen of an anti-lynching protest in the 1930s. It was 1934, in DC, and Howard University students and the NAACP were protesting officials’ refusal to consider anti-lynching laws at the National Crime Conference. But I’d misremembered, and instead of signs, the protestors were wearing nooses around their necks. And standing on the grass. Because two days before, police had arrested protestors outside the Conference, held at DAR Hall, for holding signs on the sidewalk. And they refused to issue a permit to protest.

The first time the idea was discussed to add Confederate windows at the National Cathedral was three years earlier, in 1931. So if Kerry James Marshall’s windows’ depictions of seemingly innocuous protest demands feel inadequate in the current context of anti-Black violence and terror, at least they’re historically accurate to the world that conjured them. That they exist where they do shows the progress that’s been made over the last hundred years. And if that doesn’t feel like enough, good: it’s not supposed to.