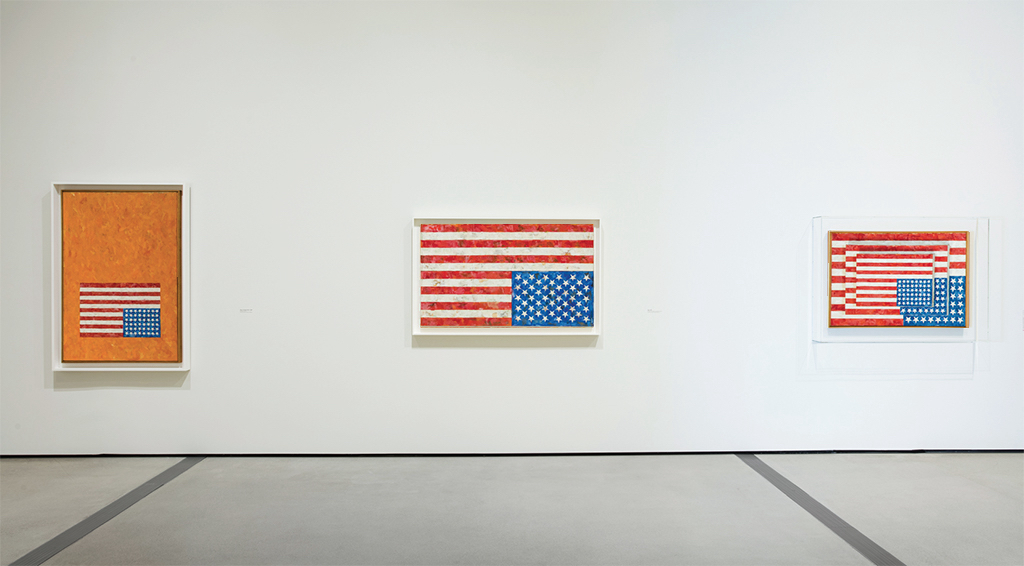

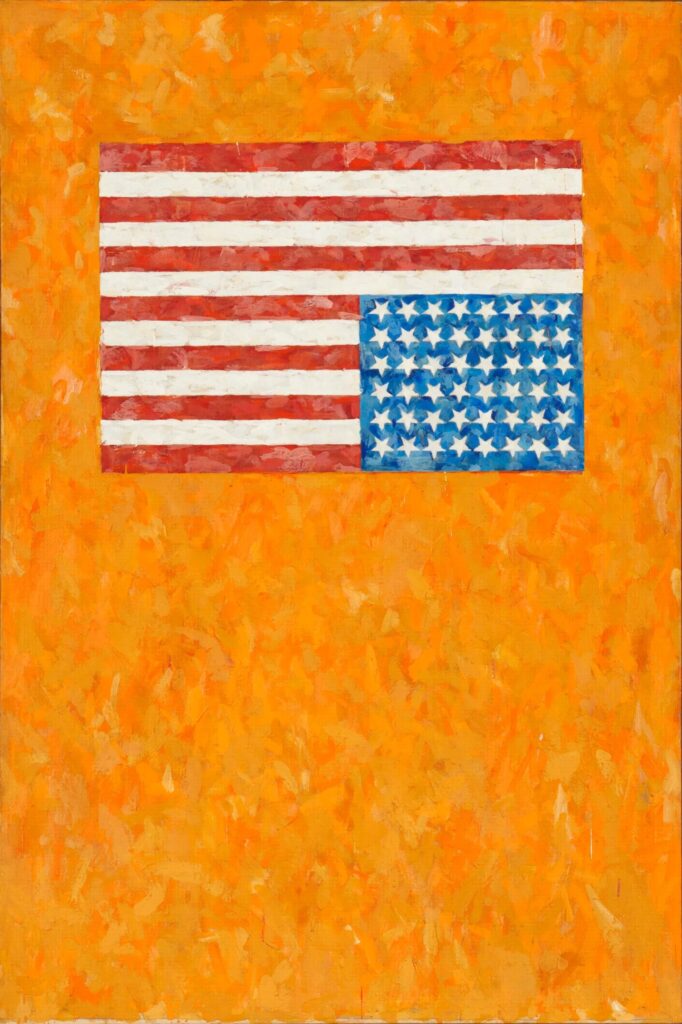

When I first thought of it, it was still within the framework that has dominated art critical discussion of Jasper Johns’ work since the beginning: Is it an upside down flag painting or a painting of an upside down flag?

But this is not the moment for glib rhetorical dualities. Right now an upside down flag does not have to be either “a signal of dire distress in instances of extreme danger to life or property” or a political protest. With active attacks on democratic institutions and the rule of law under the US Constitution, it can be and must be, unfortunately, both.

The urgent moment and the symbolic meaning also do not accommodate ambivalence over the recent co-option of the upside down flag by right-wing extremists. No one has been wronger than the hapless postdoc who thought she was describing two right-wing factions in NPR’s upside down flag explainer last June:

“There are people who [consider themselves] ultra-patriots — who think of themselves as defending American principles and institutions from corruption. There are also those who seek to actually overthrow the U.S. democratic system entirely because they don’t believe in democracy,” she said. “That second sect don’t typically use the upside-down flags, but the first sect who view themselves as ultra-patriots do.”

It turns out that as soon as they seized power, the qanon freaks and 2020 election overthrowers and denialists; the khaki-clad neo-nazi mobs; the complicit Supreme Court justices; and the bought think tankers at the Heritage Foundation, who all flew an upside down flag while posing as ultra-patriots, began violating American principles and pumping corruption into the institutional system they’re actively trying to dismantle from the inside.

But ever since he started pursuing his American Flag Dream in 1954, the relationship status between the American flag and Johns’s Flag has been complicated. It was ambivalent enough in 1958 to scare off MoMA’s trustees, who parked it at Philip Johnson’s place until the McCarthyist wave of anti-gay, anti-communist hysteria subsided.

In 2006, in the middle of the Iraq War phase of the US’s Global War on Terror, Anne M. Wagner revisited the fraught political implications of Johns’s Flag—for the individual:

Why study Flag? I have done so because I am a US citizen; because the United States, backed by its allies, is once again engaged in murderous warfare; and because, as Johns implicitly acknowledges, actions carried out in the name of the nation raise the issue of the citizen’s ambiguous belonging to the state. If those ambiguities are structured into US hegemony—woven into its double logic, the logic of force and consent—has the time not come to examine again, with microscopic precision, one’s own belonging within that overarching logic and what it conceals? What are its materials? How deeply do they lie buried? According to what allegiances are they deployed?

Now with a president who brags about the warrantless ICE arrest at Columbia of a student with a green card for protesting a genocidal war, and who claims unaccountable power to negate the constitution’s promise of birthright citizenship, and who mobilizes the government to erase the existence of trans and non-white people, the actions carried out in the name of the nation are once again raising the issue of belonging, minus the ambiguity.

Wagner felt that Johns, a gay veteran, was well aware of these conflicts when he made Flag—and when he kept making flag-related artworks throughout the next sixty years of political and cultural upheavals. I agree.

Would Johns paint an upside down flag today? I have no idea, and would absolutely never ask. I’ve learned from Michael Crichton that he does not take requests. So my Sturtevant-style repetition of a c. 2025 upside down Johns Flag is not an interpolation of what Johns might do—or might have done, if he were still painting—but its own speculative thing. [Technically, since it’s just a circulating jpg study I made last night, and not even a real object, it’s doubly speculative.] After testing several options, I went with the Flag on Orange Field II (1958) precisely because its composition meant its nature could be immediately understood. [Or so I thought; several people have still interpreted it as a new painting by Johns.]

But this gets me back to my original question: painting of an upside down flag, or upside down flag painting? In her 2006 essay Wagner mentions a “little-known” Johns Flag from 1971 that David Geffen sold in 2004, that points to an answer:

[N]ot only is it a vertical image, it is one that sees the flag, however improbably, from the wrong side. This means that were it turned horizontally, the familiar canton would appear, against centuries-old custom, on the right. Again, I think we can take the measure of Johns’s experiment by insisting on the literal implications of what, in representation, he has tried to do: to provide a viewer with a different position—an inverse position—from which to contemplate the national sign. [emphasis in original]

Well, yes and no, or rather, no and yes.

Flag (1971) is definitely the first vertically oriented flag painting Johns made. And it is definitely not the same composition just rotated 90 degrees. But Johns’ orientation here is neither either experimental nor “wrong”; it follows the guidelines from the U.S. Flag Code for displaying a flag vertically on a wall, or in a window—from the outside/viewer’s perspective. He would later make three double vertical flag paintings, along with several drawings and prints, all in this same orientation.

The inverse that matters here is on the back. According to the catalogue raisonné, Flag (P181) is the only flag painting on which Johns drew an “upward pointing arrow” to indicate a “correct orientation.” So that leaves at least 31 flag paintings for which the artist has not specified a single orientation.

One could argue, then, with that one exception, every collector, curator, or museum could hang their Johns flag painting upside down if they needed a powerful signal of dire distress or emergency. One could also argue that the ongoing destruction of the US government and its constitutional and democratic infrastructure would present such an emergency.

Previously, related: Untitled (Mrs. Alito’s Flag), 2021-24