April 18th, 2025 was the 250th anniversary of the lighting of the lanterns in Old North Church, which signaled to fellow patriots across Boston Harbor that British troops were on the move. Political historian Heather Cox Richardson recounted the incident in a riveting and inspiring talk at the Old North Church.

Her emphasis was on the ordinariness of the people involved, and the seeming smallness of their actions, even though they faced real, dangerous consequences. This is all the more important now as we ourselves are confronted with choices to do the next right thing without assurance of the impact. [the YouTube channel that posted video of the speech could not be more random, and its nascent virality is leading it to be reuploaded, so I’ll watch to keep the most authoritative version here.]

The star of the “one if by land, two if by sea” story is Paul Revere, but Cox Richardson gives full attention to his collaborators, John Pulling, Jr. and Robert Newman, who had access to the Old North Church and who actually lit the lanterns. [As a keyholder for the church, Newman was arrested the next morning, and Pulling bounced to Nantucket.]

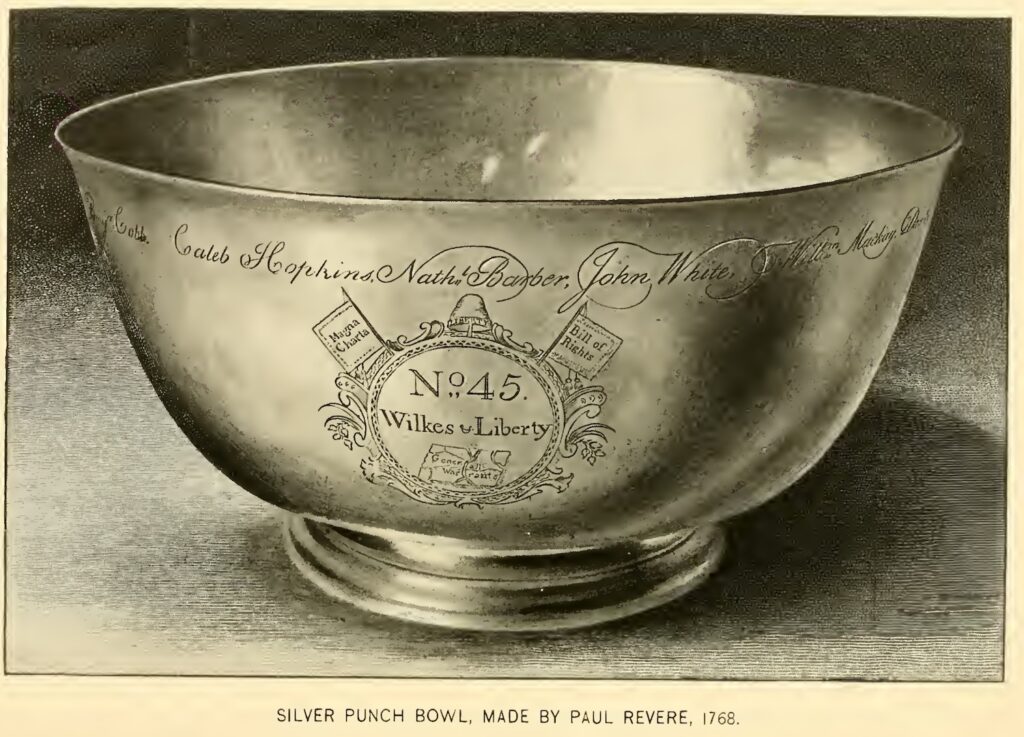

The seeming insignificance of a particular action of resistance was on my mind when Liz Deschenes posted a picture of the Sons of Liberty Bowl on instagram today. Conceptually, at least, I’m a Paul Revere engraving fan, but I confess, I’d never given the Sons of Liberty Bowl much thought. And despite what the MFA Boston says, if you had asked me to tell you the nation’s third “most cherished historical treasures after the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution,” I would never in a million years have said the little punchbowl Paul Revere made for his friends.

But we are in different times, and have a different relationship to tyranny than we did even a few months ago. And it has been worth giving the bowl a new, closer look.

Revere was commissioned to make the bowl by fifteen fellow Associates of the Sons of Liberty—whose names are engraved around the rim—to honor the 92 members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, “who, undaunted by the insolent Menaces of Villains in Power, / from a Strict Regard to Conscience, and the LIBERTIES / of their Constituents, on the 30th of June 1768, / Voted NOT TO RESCIND.”

Which, tbh, kind of esoteric? But that was the point, and everyone at the time the bowl was made understood the significance of what it commemorated and how it did so. It was a deliberately private, even secret, act of resistance, to further organize that resistance. The thing they voted not to rescind was what’s known now as the Massachusetts Circular Letter, co-written earlier in 1768 by Samuel Adams. It rejected new taxation without representation, and escalated the colonialist call for self-government. The Massachusetts House approved and circulated it to all the colonies, and the king sent an order to the body to rescind or be dissolved.

As it says right on the bowl, they voted 92 [-17] not to rescind. And the British governor dissolved the House. Demonstrations and violence against customs collectors and British military occupation would follow. The Boston Tea Party and the Boston Massacre, and onward through the buildup to the call for independence. But no one knew that when Paul Revere made the bowl in the weeks after the vote.

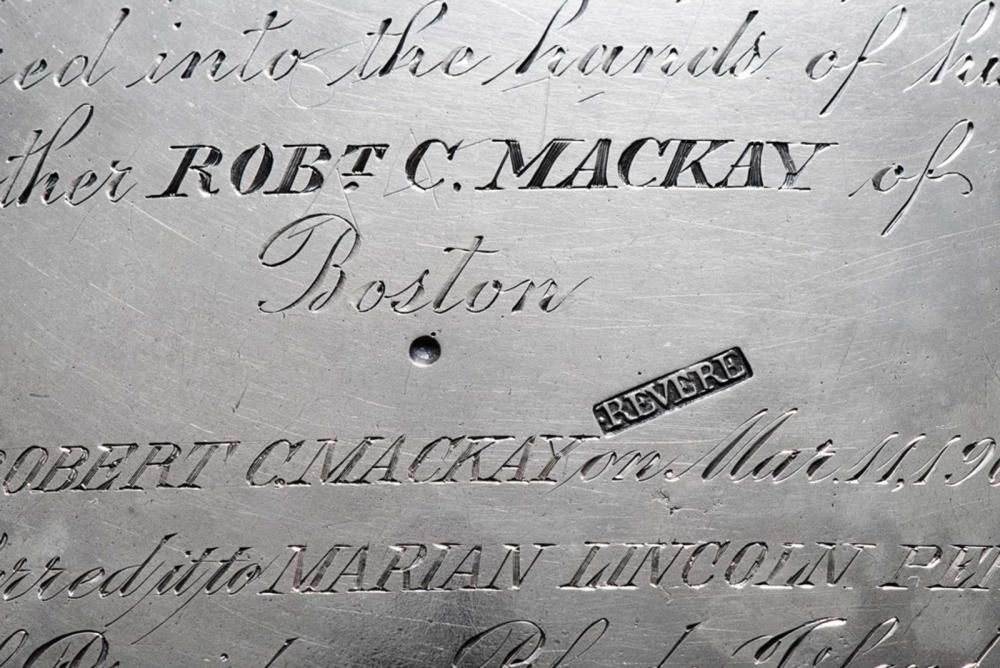

Given the real risks of being associated with the Sons of Liberty, it seems legit insane to inscribe your members’ names on a bowl, and then to stamp your own name on it. So this bowl was made and used in secret. The Colonial Society of Massachusetts’ history of the bowl notes that its manufacture does not appear in the records of his shop, despite it taking up to 100 hours to produce.

It was made from 45 ounces of silver, and designed to hold 45 gills of rum, and was used for toasts at meetings of the Sons of Liberty. No. 45, which is also inscribed on the bowl, is a reference to the volume of a periodical by radical Whig John Wilkes, who defended freedom of the press and criticized agents of the king for lawlessness and warrantless arrest. After the first few toasts to the king and country, the remaining 30-40 were made to Wilkes and other critics of tyranny, and to the various principles of liberty and self-governance the colonists were demanding.

But again, like the Sons of Liberty themselves, the bowl existed in secret. One of the commissioners, William Mackay, bought it from the others, and it descended in his family. The first public appearance of the bowl might have been in 1874, when it was brought to the Massachusetts Historical Society as the “sole relic of an event which must have set King George’s teeth on edge.” So they missed one centennial, and since two additional engravings documenting the bowl’s purpose and provenance are only known to have appeared “since 1875,” it sounds like the underknown bowl missed a couple more.

A profile of the bowl in the Boston Morning Herald in 1895 was republished as a pamphlet, with photos, and one subplot of the story is that other descendants of the commissioners had lore about the “famous bowl,” but no idea where it was. It also made it sound like a Mackay family relic, passed down like a membership in the Society of the Cincinnati. Yet within seven years, in 1902, a Mackay sold it to a Marston, descendants of another of the fifteen commissioners. they kept it for one generation before offering it to the MFA in Boston in 1949, “an era characterized by high patriotic fervor.”

So just as Longfellow’s 1860 poem transformed a little-known incident into a unifying rallying point and made Paul Revere a hero, the high patriotic fervor of the early 20th century and a public fundraising drive turned a private heirloom into a national treasure.

Which is all to say, the acts of courage and resistance we celebrate are just the ones we know about, but the revolution that came was the result of many more lost to history.

Prof. Cox Richardson said that “Paul Revere didn’t wake up on the morning of April 18, 1775, and decide to change the world…Like his neighbors, Revere simply offered what he could to the cause: engraving skills, information, knowledge of a church steeple, longstanding friendships that helped to create a network.”

But we also see that by 1775, Revere was deeply committed, entrenched, and invested, offering what he could to the cause, and building the community that would go on to resist and defeat the tyranny that loomed ahead of it.