In 1989, artist Rudolf Stingel published Instructions, an illustrated booklet showing how to make one of his silver paintings. “He challenges the process of creating a painting and questions the concept of the canvas and that of authorship,” says Christie’s in a paraphrase of the curator Francesco Bonami. Christie’s is selling a 1998 silver Stingel painting [whatever that means, we’ll get to in a second] in London in a couple of weeks. Christie’s explains how they’re made:

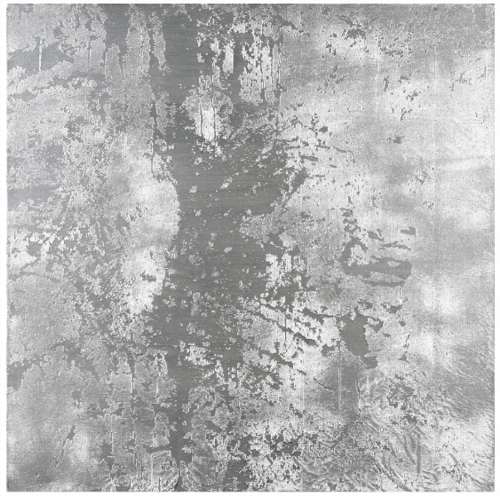

The works begin with the application of a thick layer of paint in a particular colour, in the case of the present example silver enamel, to the canvas. Pieces of gauze are then placed over the surface of the canvas and silver paint is added using a spray gun. Finally, the gauze is removed, resulting in a richly textured surface. When seen in conjunction with the DIY manual, the Warholian nature of Stingel’s work is difficult to refute: technical methods of factory-like production, which are openly communicated and question authorship, contrast the provoked coincidences that result in individual monotypes. Particularly, a parallel to Warhol’s so-called Piss Paintings comes to mind: both artists test the methods of what can be considered painting, while simultaneously emphasising the carnality of the practice by combining coincidence and will in a process solely focused on the canvas’s skin. With Stingel’s works, the aggravation of the derma creates the rapture.

I love it, except that the challenge to authorship is merely a conceptual pose, one refuted most immediately by Stingel’s signature on this painting and its £120,000 – £160,000 sale estimate.

Bonami reads the Instructions as “tricking you into learning how to do a painting for someone else.” Which, though, is the neater trick: following the artist’s instructions and making a Stingel for myself, or getting someone to spend £200,000 on an identical painting from the artist’s factory because it has Stingel’s autograph on the back?

The invocation of Warhol and the Piss Paintings is illuminating, and not just for the works’ focus on a painting’s surface or skin–or derma. Such process-oriented practice, which embraces a degree of randomness, conveniently results in serial works of unfakeable uniqueness. They don’t need stamps of authenticity; the object is its own fingerprint. With minimal documentation at the time of creation in his studio, Stingel’s collectors will never face scandals of authorship like those engulfing the Warhol Estate’s authentication board. According to the board’s self-contradictory interpretations of Warhol’s Factory processes, mass-produced silkscreens that Warhol never saw can be accepted as works, while a documented self-portrait can be rejected repeatedly.

On the flip side, though, if Stingel really wanted to challenge authorship and treat each painting as a “cell” that only gains meaning from its connection to countless others, he’d get more traction by treating the world’s DIY Stingels as intrinsic parts of his own work. Locate, document, and show them in galleries and museum retrospectives. Let them be bought and sold in the secondary [primary?] market. Then when one of those works shows up at Christie’s, we’ll talk again about questioning the concept of authorship.

Lot 319: Rudolf Stingel (b. 1956),

Untitled

signed and dated ‘Stingel 98’ (on the reverse)

oil and enamel on canvas

32 x 32in. (81.3 x 81.3cm.)

Executed in 1998

Estimate: £120,000 – £160,000 [christies.com]

Rudolf Stingel – Selected works [paulacoopergallery.com]