Via Cityfile, we learn that Paris photographer Patrick Cariou has filed suit against Richard Prince, Gagosian [the man and the gallery], and Rizzoli for copyright infringement. Prince used photos from Cariou’s 2000 book Yes Rasta in the Canal Zone paintings he just showed at Gagosian NY last month [Rizzoli published a book of Prince’s works, too.]

In the suit [embedded pdf at cityfile], Cariou repeatedly calls Prince an “appropriation artist” [quotes included], who “boasts” of “copying” other peoples’ work. What’s different in this case, Cariou argues, is that instead of copying “anonymous commercial imagery, such as advertisements,” Prince has copied Cariou’s work. Which happens to be hard-won portraits of camera-shy Rastafarians, “approximately 100 strikingly original black-and-white photographs, mostly close-up portraits of stern, mystical-looking men within a distinctive tropical landscape.”

As fun as it might be to watch the bedlam if Cariou was granted the relief he seeks–namely, monetary damages for copyright infringment and conspiracy; having every painting, scrap, scan, page and byte of the infringing works turned over to him and destroyed; having Gagosian send out notices to the buyers of Prince’s paintings that it is illegal to display or sell their infringing works–I don’t see Prince or his people losing much sleep over this case.

First off, it’s not like the advertising imagery Prince has used before is either “anonymous” or the product of happenstance. When Prince’s versions of his Marlboro Man photos were shown at the Guggenheim in 2007, the NY Times interviewed well-known photographer Jim Krantz. He clearly had issues with the appropriation–rephotography in this case–and if he hadn’t assigned his copyright to Philip Morris, Krantz would probably be able to get a settlement from Prince, just like the rephotographed Brooke Shields photographer Garry Gross did.

Reading Cariou’s complaint, you’d almost think Prince was simply re-presenting Cariou’s images as his own. In fact, Prince’s process and his use of Cariou’s images are much more complex, and it will almost certainly be the basis for a judgment in Prince’s favor. As the Canal Zone press release explains, process is central to the works:

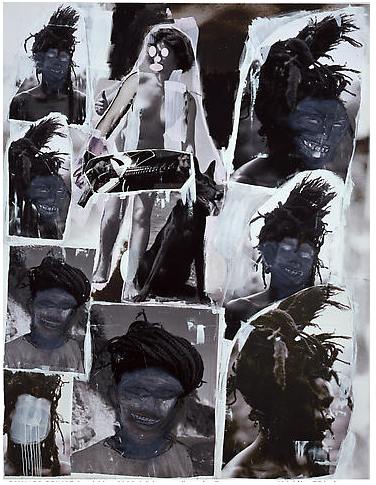

..[the paintings] are, literally, “put together,” like provisional magazine lay-outs. Some images, scanned from originals, are printed directly onto the base canvas; others are “dragged on,” using a primitive collage technique whereby printed figures are roughly cut out, then the backs of those figures painted and pasted directly onto the base canvas with a squeegee so that the excess paint squirts out on and around the image. On top of this are violently suggestive swipes and drips of livid paint and scribbles of oil-stick crayon which, together with the comic, abstract sign-features that mask each figure’s face, add to the powerful push-pull between degree and effect. This has become a completely new way for Prince to make a painting, where much of what shows up on the surface is incidental to the process.

Collaging and reworking and changes in format, size, medium and styles, they’re all transformative creative techniques that were directly addressed in the 2005-6 case, Blanch vs. Koons, where the same court [the US Southern District] found that Jeff Koons did not infringe Andrea Blanch’s copyright when he collaged a pair of legs from her photograph–published in a 2000 issue of Allure magazine–in a painting. Blanch lost on appeal, too.

Prince’s process means his works, like Koons’s, will almost certainly be declared transformative, not derivative works, and as such, they’re fair use, not infringing. But Cariou’s filing also sows the seeds of another fair use argument, that of criticism and commentary. Cariou waxes on about the Rastafarians,

…a spiritual society, living simply, independently, and in harmony with nature, apart from the industrialized world of environmental pollution and materialism which they reject and refer to as “Babylon.” Naturally, the Rastafarians do not trust outsiders, such as Plaintiff, and it was only after living with them for years that Plaintiff was finally permitted to photograph them.

Prince’s Canal Zone project is precisely a critique of this sort of European Caribbean romanticism:

Prince has transformed the former reality of his birthplace [i.e., the Panama Canal Zone] into a fictive space: “Canal Zone” provides an anarchic tropical scenario in which extreme emanations of the (white American male) id – fleshy female pin-ups, Rastafarians with massive dreadlocks, electric guitars, and virile black bodies – run riot.

And then he takes it further, critiquing utopias wherever they’re found [sic], including Thomas More’s original Utopia, an island “that possessed a seemingly perfect socio-political-legal system.” Sound familiar?

By roughly juxtaposing distinctly unclassy porn against Cariou’s photos, Prince calls bullshit on the myth of the White Man’s humble, harmonic embrace of and by the “simple,” “stern,” “mystical” Rastas. Cariou might as well sue Andy Samberg and NBC for defamation while he’s at it. He’d probably have a better case.

Richard Prince and Larry Gagosian slapped with suit [cityfile via afc]

Canal Zone, Nov 8 – Dec 20, 2008 [gagosian]

Is it even in print? Could the controversy lead to a new edition? LIMITED AVAILABILITY – Yes Rasta by Patrick Cariou [powerhousebooks.com]

If the Copy Is an Artwork, Then What’s the Original? [nyt, 2007]