I’d had the idea all worked out, and the script outline–or a draft of it, anyway–all ready for a couple of years, but my paternal grandfather Champ passed away before I was able to make the original documentary about him I’d envisioned.

In 2001, I rather impetuously set off to interview my grandmother Avis, his wife, about their life. Which is when I learned he’d been in a band. With outfits and everything. A dance hall country band that traveled the desert towns in Utah and thereabouts. It’s how he and my grandmother had met. I guess that made her a groupie.

As long as I’d known, he was only ever the gregarious, Center Street businessman, the guy who ran the dry cleaners where everyone took their Sunday clothes. But my childhood memories of him picking songs for me on his guitar changed as I imagined how, for him, playing music was also a reminder of the life he’d given up when he had a family.

I’d met my great uncle Wayne, Champ’s brother, twice. At Champ’s funeral, and then a little over a year ago at Avis’s. It occurred to me that I should talk to him, hear his stories, see his photos and mementos. Because he is only one of a few people left who can provide some sense of my grandfather as a young man.

And so over Christmas, I took a few hours to visit with him and his wife. And that’s when he told me in addition to a musician, my grandfather had been a hobo. In central Utah in the Depression [aka, the last Depression, -ed.], there wasn’t enough work in your tiny hometown, so you had to hit the road to find a job.

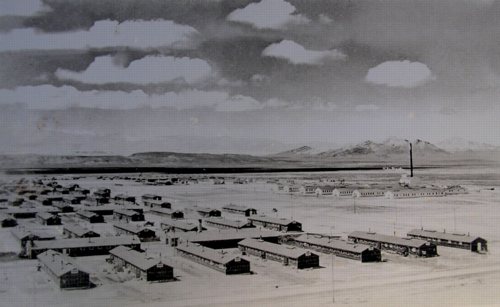

And in the Summer of 1942, after he and Avis married and had one, maybe even two kids, he left them and traveled to the desert town of Delta, where he got a job building the Topaz Internment Camp, where over 8,000 Japanese Americans were imprisoned for up to three years.

Like most all the internment camps, Topaz Camp was built in a hurry, on a grid, using plans adapted from military barracks. Tarpaper-covered sheds were finished in sheetrock on the inside, and each block was divided up into apartments in a range of sizes–all too small–to accommodate different sizes of families. If they wanted any furnishings beyond the military cot provided, the internees had to build it out of the scrapwood the carpenters–including my grandfather–left behind.

Specifics of the camp’s buildings and design were collected by the National Park Service, which conducted a survey in 2005 of all the sites and artifacts associated with the imprisonment of Japanese Americans [pdf], in order to identify candidates for National Historic Landmark status. In their report, it says,

Local craftsmen were used, but the requirements were not always stringent; in Millard County, Utah, near the Topaz Relocation Center, “Topaz Carpenter” is still a derogatory term, since anyone who showed up at the site with a hammer would be hired.

And a damn good thing, too, I guess. It’s an odd feeling to suddenly find oneself–or one’s family–on the wrong side of history. On several wrong sides, actually, if the “Topaz Carpenter” dig were real. I don’t doubt that some people say/said it, but it so happens that my maternal grandmother grew up in Delta, and neither she nor her people seem to have ever heard the term.

Until I posted about it, the NPS survey was the only Google reference to Topaz Carpenters. It was someone’s insult generations ago in the middle of BF Utah, and it ended up in a government history survey, sounding pretty official. Part of me wants to defend my grandfather by disproving the term’s popularity, as if that would somehow change its accuracy. Because he really was a guy who showed up with a hammer, got hired, and who, in just a few weeks, built a prison camp for his fellow Americans.

After the camp was closed in 1945, the barracks were either torn down or sold to local farmers, who used them as barns, even a home or two. There was one left nearby–half of one, really, a 20 x 60 section, being used as a shed–which was donated and restored in 1991 to help create the Topaz Museum. [images: greatbasinheritage.org] Which is now on my list of places to visit next time I’m in Utah with a couple of days to spare.

Previously:

This [Japanese] American [Internment Camp] Life [greg.org, 2007]

Ansel Adams Japanese American concentration camp photos from Manzanar [greg.org, 2003]