Janus Films is releasing the remastered version of Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Dekalog in theaters before Criterion releases it on disc. Here is the trailer.

Seeing Dekalog in theaters in the early 1990s was one of the formative cinematic experiences of my life. I may have to do it again. The kids can find their own way back to school.

‘Dekalog’ Exclusive Trailer: Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Magnum Opus Returns To Theaters This Fall [indiewire]

Pre-order Dekalog (The Criterion Collection) for Sept 27 release [amazon]

Category: the souvenir series

On Dennis Johnson’s November

On and off for the last several months, I’ve been soaking in an extraordinary piece of music, and trying to get up to speed on the series of minorly monumental circumstances that are bringing it out of obscurity.

In 1959 Dennis Johnson, a college friend of LaMonte Young, composed November, a six-hour piano piece that basically gave birth to the minimalist music movement as we know it. Young, never shy about his own importance, credits November as the source and inspiration for his own ur-minimalist composition, The Well Tuned Piano. It was all there in November first.

But except for a rough 2-hour recording from 1962, Johnson’s work had faded from consciousness, discussion, performance, and history. And Johnson himself had disappeared from the music landscape. Until musicologist Kyle Gann began investigating it, and reconstructing the score. Then R. Andrew Lee recorded it. And it got released last spring on a 4CD box set.

I found November through musician Ben.Harper’s blog, Boring Like A Drill. The unfolding of November‘s story across several years of posts is convoluted, but really wonderful. Here’s a bit of his description of attending a live performance of November by Lee, timed to the CD release:

Over five hours, the music works a strange effect on the listener. The intervening decades of minimalist and ambient music have made us familiar with the concepts of long durations, tonal stasis, consistent dynamics, repetitions, but November uses these techniques in an unusual way. The sense of continuity is very strong, but there is no fixed pulse and few strict repetitions. The slowness, spareness and use of silence, with an organic sense of rhythm, make it seem very similar in many respects to Morton Feldman’s late music. The harmonic language, however, is very different. Johnson’s piece uses clear, familiar tonality to play with our expectations of the music’s ultimate direction, whereas Feldman’s chromatic ambiguity seeks to negate any feeling of movement in harmony or time.

The semi-improvised nature of November adds another element to a performance. It was interesting to watch Lee relax as he moved from the fully-notated transcription of the piece’s first 100 minutes, into the more open notation that made up the next three hours of playing. He seemed to go into a serene state of focused timelessness, perfectly matching the music he was playing.

November reminds me of a CD by Gabriel Orozco titled “Clinton is Innocent,” on which the artist improvised some random one-handed note clusters that were meant to evoke memories of the piano music of his childhood home. I used some of Orozco’s music in my first short film, Souvenir (November 2001), but for these months now, the coincidence of Johnson’s title has had me rethinking that score.

Late November [boring like a drill]

Gann talking about November on WNYC’s Spinning on Air last August [wnyc.org]

Buy R. Andrew Lee’s recording of Dennis Johnson’s November from Irritable Hedgehog [irritablehedgehog.com]

UPDATE AN HOUR LATER: D’oh, there I go again, I just listened to the WNYC show again.

It’s A Mozingo Thing

My great great grandmother had an awesome name: Mary Argent Mozingo. She was married to the equally well-named Ruffin Sullivan. They were country people, farmers, I suppose, in Wayne County, North Carolina. I knew their daughter, my great grandmother, who lived to be 105, but I never heard her talk of her parents. We found their names when we were in the market for names, and were surfing through family history records. My wife vetoed Mozingo, and my grandmother nixed Ruffin with a swiftness that hinted at family stories that did not get told very often.

While I was still campaigning for Mozingo–just, you know, as a second or third middle name, a fun option, maybe? no?–my mother did say that her grandmother always insisted her mother’s name was Mozzinger. Or Mottsinger, and if it weren’t for some ignorant census clerk somewhere who couldn’t hear or spell right, we wouldn’t even be having this conversation. In any case, it’s not Mozingo.

This was the woman who eventually edited out the stories of working in a cigar factory in Richmond as a young girl, where she won five dollars once for the quickest rolling. And who destroyed oral history tape recordings of her family’s history because of, well, I guess we can only speculate now, since those stories have been lost.

And there’s no chance that a lone census taker messed up, Ellis Island-style, on the Mozingo. If anything, my ancestors’ insecurity about Mozingo is one of the prime indicators of their true Mozingoness.

As LA Times writer Joe Mozingo found out, when he went searching for the origins of his name, which he’d always heard was Italian. Other Mozingos heard it was Portuguese, or Basque. Obviously, to almost everyone not named Mozingo, that is, Mozingo is an African name, brought to early colonial Virginia by one Edward Mozingo:

Edward had been a servant to Col. John Walker, a member of the colony’s legislature. When Walker died in 1669, his widow inherited Edward and remarried a powerful Virginian, John Stone.

Edward sued Stone for his freedom. Little is said about the lawsuit in the court record, only that there was an appeals hearing in the high colonial court, that “Divers Witnesses” testified and that the judges concluded “Edward Mozingo a Negro man” had served his term after 28 years of indenture.

Joe Mozingo’s three-part story of uncovering the Mozingo truth overflows with examples of hardship, racism, insecurity and denial that runs so natural and deep Americans have been soaking in it for centuries.

And that’s just the white Mozingos. People whose identity and racial worldview don’t have room for the complexities of rural intermarriage in 18th century America. For the Black Mozingos, meanwhile, the countervailing impact of generations of discrimination, opportunity, passing, and self-loathing still play out in a Goldsboro, NC barbecue restaurant–which turns out to be the same place we’ve stopped for lunch every summer on the way to the Outer Banks.

The ways family functions as a machine for transmitting memory are one subject of my set of 12 short films, The Souvenir Series; I think I have to add the way family desperately tries to keep things silent for centuries to the mix, too.

In Search Of The Meaning Of ‘Mozingo’, part 1, part 2, and part 3 [latimes via my cousin cara]

TV Power To The We, The People

A piece I left out of my Rirkrit’s blingy objects post yesterday may be more important than I originally thought, and for more reasons than its shininess.

Untitled 2005 (the air between the chain-link fence and the broken bicycle wheel) was the Guggenheim installation Rirkrit got to do for winning the Hugo Boss prize. It was a low-power, unlicensed TV transmitter, the blueprints for building your own, and wallpaper full of texts about freedom of speech, the revolutionary power of media, and the political and economic contradictions of the FCC.

I was thinking of mentioning it because it atypically included structures made of both plywood and of mirror-finished steel. The glass and steel vitrine held the TV transmitter, the source of media power, while the similarly sized plywood shed contained the antenna and a TV. The steel cube was closed off; the ply cube had a door, windows, and 2×4 furniture. Oh, and an antenna made in the form of Marcel Duchamp’s bicycle wheel.

The instructions for making your own TV station were printed on posters, made available on the floor in a Felix-style stack. If there were a more explicit evocation possible of contemporary art and the political clashes of the 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s, I guess I can’t think of what it was. Except maybe for Rirkrit’s collaboration the next year with Mark di Suvero to create an Iraq War-era version The Peace Tower.

Untitled 2005 (the air between the chain-link fence and the broken bicycle wheel), detail, via

And then I found Holland Cotter’s unexpectedly extraordinary-in-parts review of Rirkrit’s 2005 Guggenheim show:

The installation is basically a bare-bones statement of the practical fact that anyone who wants to participate in shaping the communications media that are shaping the world at large can do so. “Everyone is an artist” was Joseph Beuys’s potent rallying cry in the 1960’s and 70’s, which made artists and “the people” one. Mr. Tiravanija, who has learned much from Beuys, adds his own variation: “Everyone is a broadcaster. Make this transmitter at home.”

Hmm, mirrored TV: Untitled 2005 (the air between the chain-link fence and the broken bicycle wheel), detail, via

At the same time, he has customized his own version with a couple of features that are not necessarily meant for replication. One is the glass box encasing the transmitter. Its presence is symbolic, a reminder of how resources that should be available free to everyone become the closely guarded valuables of a privileged few.

Yow, that suddenly puts a polemical shine on Rirkrit’s deployment of chrome; makes me not want to get caught with a shiny ping-pong table when The Revolution comes.

But then, in one sense, it’s already here.

The complicated connection between politically charged art of the 00s and today’s Occupy Wall Street protests grew starker as I read Martha Schwendener’s sharp piece in the Voice [thanks, Tyler] about the implications of #OWS for art, and vice versa:

Art was, for a long time, a utopian model. But with bohemianism eroded by gentrification and the 1 percent end of the art spectrum devoted primarily to vapid, overfunded gestures, you wonder if a recent Columbia University symposium, which described art as “a catalyst and platform heralding justice, solidarity, and a peaceful future” is nostalgia–or just wishful thinking.

Schwendener’s piece read to me like a wakeup call for artists: “Practice [sic] is over. This is not a drill.”

Which made me think right back to Cotter’s opening, clear-eyed for a child of the 60s, a reflection on the very idea of “Power to the people”:

Who were “the people,” anyway? Blue-collar workers, African-Americans in the civil rights movement, immigrant laborers. Students? Some, though even engaged young people tended to want to help the people rather than be the people.

There’s a Rirkrit t-shirt in there somewhere, I can just feel it.

Art Review | Rirkrit Tiravanija: Work Whose Medium Is Indeed Its Message [nyt]

What does Occupy Wall Street mean for art? [villagevoice]

Defendant’s Request #2

While doing some family history research, I discovered that one of my grandmother’s cousins, Charles Burr, a farmer in Burrville, Utah, had been killed by W.A. “Boss” Lipsey, a neighbor, in March 1943.

The Burr family version of the story says that Lipsey had run-ins with many other farmers in the valley, and that, after a water rights argument, he lay in wait in the bushes until Burr ventured out to feed his animals, and then he shot him in the back with a 12-gauge shotgun.

A version of the story online mentions a years-long feud between the two, and specifically referred to a fight a couple of years earlier between Burr, Lipsey, and Lipsey’s sons.

I just received the court records for Lipsey’s murder trial, including some information the defense drafted for the judge to pass along to the jury during their deliberations. Here is one, with the judge’s handwritten notations in italics:

DEFENDANT’S REQUEST #2.

The Court instructs the jury that the evidence in the case shows, without dispute, that on August 7, 1941, Charles Burr, with his fingers and hands, dug out the left eye of the defendant.

Refused

July 1, 1943

John L. Sevy, Jr

Judge

The Burr account I have ends:

The family could not believe the verdict of second degree murder with a fifteen-year prison sentence with eligibility for parole after five years. Needless to say, the Burr family did not believe justice had been served.

The account does not mention what I found from newspaper accounts: that Boss Lipsey was denied parole once and appears to have died in the Utah State Prison. As of 1995, when this Burr family history was privately published, it doesn’t sound like there’s been much attempt to reconcile the Lipseys and the Burrs’ versions of their intertwined history. I don’t know if I’m up for trying, or if I’m too close or too far to do it.

05/12 UPDATE Thank you, Google. I have heard from one of Boss Lipsey’ great grandchildren that Boss was, in fact, released from prison shortly before he died. As one might imagine, their family stories emphasize details that the Burr versions omit, like that Lipsey was in his mid-70s when he and 40-yo Charley first fought over their turns for the Koosharem Reservoir’s irrigation water. I may end up putting the Burr family version of the incident online sometime; it was written by Charley’s son Ned, who was around 13 at the time his father was killed.

On Looking Into Tarkovsky’s Mirror

I just watched Tarkovsky’s 1975 film The Mirror for the first time as an adult, basically; when I saw it in college, I had no clue and was bored out of my gourd by it. In fact, for a long time, I’d conflated it, burning houses and whatnot, with The Sacrifice.

Anyway, the largely plotless, highly autobiographical film is a memory-like collage of documentary footage and vignettes set in disparate time periods. When I say, plotless, though, I mean it’s a movie about a guy who spent ten years trying to make a movie about his childhood purely as an excuse to show the awesome scenes of a Soviet military balloon from the Spanish Civil War. At least that’s how it looks to me now.

Previously: an image of a guy on a balloon inspecting Echo II at Lakehurst, NJ

On Remembering The Great Kanto Earthquake

NYT Mag staffer Aaron Retica posted some childhood recollections from Akira Kurosawa of the horrible aftermath of the 1923 Kanto Earthquake, and the xenophobic hysteria that followed.

It makes me wonder, though, if Kurosawa ever spoke about his decision not to depict the earthquake in film.

Some Pointers, Or What To Do With Neutra’s Gettysburg Cyclorama Center?

The Park Service’s stated goal for Gettysburg is the “rehabilitation” of the battlefield to its 1863 condition by removing modern structures like Richard Neutra’s Cyclorama Center [designed, it should have been noted a long time ago, with Robert Alexander] and the visitors center next to it [already gone] which are built on “hallowed ground.” Which is not quite so simple.

In Gettysburg: memory, market and an American shrine, his 2003 history of the ongoing cultural battle over the site and its meaning, Jim Weeks looked at the controversy over the Park Service plan to create a big, new privately operated visitor center/museum offsite. This wasn’t “Disneyfication,” it was, in the words of John Latscher, the Gettysburg superintendent who spearheaded the deal, “re-sanctifying” the battlefield. [emphasis added on the tiny but powerful rhetorical device that automatically transforms anyone who disagrees into John Wilkes Booth.]

The rehabilitation/re-sanctification plan to remove post-1863 structures does have some loopholes: anything in the middle of the battlefield but on private land across the street, as long as it serves popcorn chicken and/or deliciously dark chocolate pies for a limited time only; the 1392 or 1600 markers and monuments placed by “the veterans themselves,” or whomever; and the three remaining observation towers the War Department built.

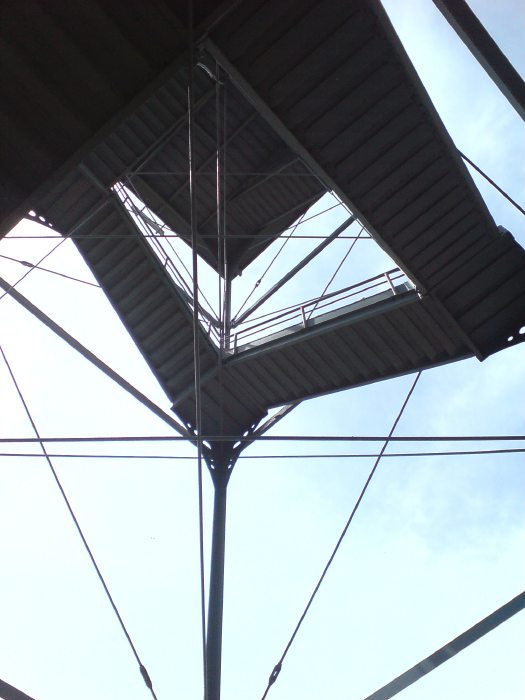

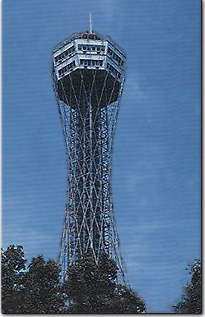

Let me go on record that, should it ever be threatened with demolition, I will email every architect and journalist I know to save the observation tower on West Confederate Avenue; that thing is a freaking masterpiece. Let’s get that out there right now, because I don’t find much information or discussion about it at all. [Here’s another of the three, dated 1895, the year the War Dept took charge of the Memorial Park, which is super-short. It looks like there were structural problems, and it was chopped in 1960. Note that it wasn’t torn down completely; I think I’ll come back to that in a minute.]

What do you get for your steep, 6-7 story climb up the steel cage? A great view, of course. But also understanding. Context. Orientation. It’s the place where people tell stories of troop movements and battle strategies. There is much pointing. All across a vast landscape like this, we saw people orienting themselves, spotting landmarks, and telling stories. They were mapping the action and the meaning, translating history onto the site in front of them.

Weeks’ book notes that observation points have been a popular and vital feature of visitors’ experience at Gettysburg from very early on. Some are natural spots, like the promontories of Little Round Top and the Copse of Trees at Cemetery Ridge. Some were built, like Round Top Park, the War Dept. towers [there used to be five], the Pennsylvania State Monument–and the Cyclorama Center. The biggest observation tower, built on private land, was seized and destroyed in 2000 after an intermittent, 26-year legal battle. Weeks draws the connection between the dioramas and orientation maps, the cycloramas–almost all of which had their origins in commercial/entertainment enterprises–and the site itself; arguably, facilitating this mental transition from representation to site was the major justification for placing the Cyclorama so close to its focal point, the top of Cemetery Ridge, in the first place.

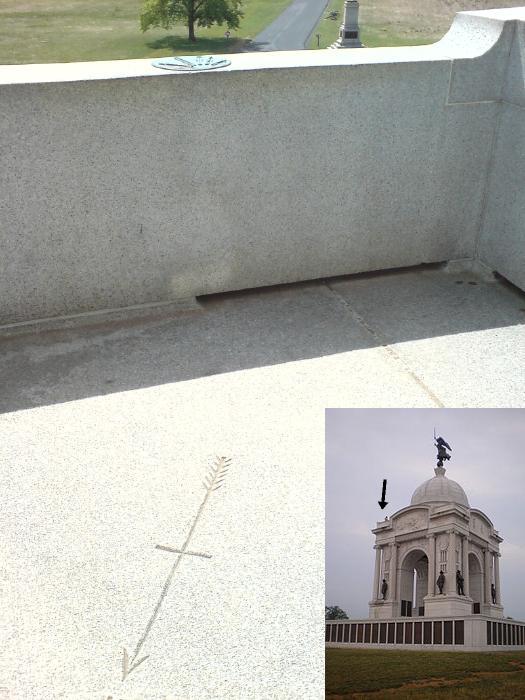

One common feature of these observation points is the orienting device: arrows pointing toward key sites or events. Here is the welded steel plate on the War Dept tower:

Which was the third one I noticed, after [1] the compass mark handcarved into the granite floor and [2] the incredible cast bronze plaques on the parapets of the Pennsylvania State Monument. [Which, by the way, is a gigantic Beaux Art mess, a Columbia Exposition knockoff whose looming, continued presence exposes the whole idea of re-creating the 1863 battlefield to be little more than conceptual cover fire to advance a subjective set of pre-determined alteration strategies.]

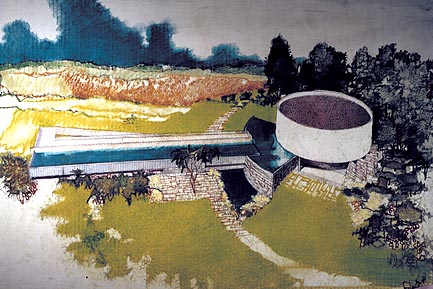

These arrows, on these structures, point, I believe, to a possible future for Neutra’s Cyclorama: restore and reconfigure it as an observation and orientation platform for Cemetery Ridge. Neutra already included an observation platform and ramp [see house industries’ photo below]; adapting the empty rotunda for observation would hew close to the building’s original function on its original site, while minimizing the loss of Neutra’s and Alexander’s key design elements.

Then there’s precedent: the Park Service’s stated strategy of 1863 rehabilitation nevertheless preserves several post-1863 observation structures, including the unassailable Pennsylvania Monument and three of the five towers apparently installed by the War Department at the founding of the Memorial Park. One is apparently historical and/or functional enough to preserve even after being truncated to just one story up–roughly the same height as the Cyclorama’s existing deck.

A Cyclorama Observation Platform would also offer something completely unique: accessibility. All other observation spots we saw involved stairs, curbs, or uneven wooded trails. [The Pennsylvania Monument’s vantage point is reached by a single, awesomely treacherous spiral staircase lined with stamped bronze paneling that’d do a SoHo loft ceiling proud.] Much of the battlefield itself–and thus the monuments scattered across it–quickly becomes inaccessible to disabled or wheelchair-using visitors.

An entirely ramp-based observation structure would enhance the battlefield experience for millions of visitors who would otherwise be confined to their cars. [Oh, look! Neutra’s already got two ramps built right in! image above: houseindustries.com]

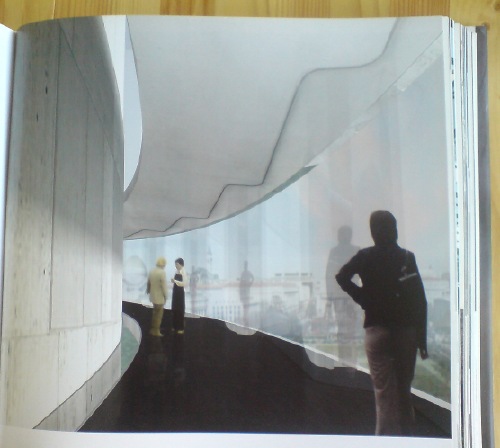

In fact, a speculative observation platform proposal has already been floated. The Boston-based architecture firm CUBE design + research used Neutra’s Cyclorama Center to illustrate a range of alternatives to strict historical preservation. One idea [above]: turning the Cyclorama as “informant” and “information hub,” by making strategic, view-framing cuts in the rotunda. It’s a pretty radical alteration, the kind of thing that keeps traditional preservationists up at night. And as proposed/rendered, I think many of Cube’s solutions go way too far. But they’re spurring discussion, not answering an RFP, and in that, they succeed.

Piercing Neutra’s rotunda in places might still work, perhaps in combination with another of CUBE’s suggestions, to place the Park Service’s historic electric relief map in the building. Or perhaps a large-scale relief map could be made for blind visitors to gauge the scale and detail of the terrain. In either case, a multi-sensory narrative program could be devised that integrates such artifacts with views out of the building onto the actual battlefield. [Something like the light and sound effects on the new Cyclorama installation, which seem to be state-of-whatever-art-these-sorts-of-things-are.]

Another possibility just came to me this morning: the 2006 proposal Olafur Eliasson made for the Hirshhorn Museum, a similarly love-to-hate, modernist concrete barrel on a major civic site. Eliasson proposed wrapping Gordon Bunshaft’s building with a suspended glass walkway that afforded sprawling views of the National Mall, something akin to the exterior escalator tubes at the Pompidou. [images: from the bookshelf-straining insanity that is Taschen’s Studio Olafur Eliasson: An Encyclopedia.]

Maybe an information-filled ramp could spiral up the inside of Neutra’s rotunda–a history of the wounded, perhaps, and their heroism and their tales of endurance and remembrance–and then let visitors out to wind their way down the outside, where they could then descend along the original ramp onto the battlefield itself. At least as far as their wheelchairs can take them.

The Park Service and Gettysburg Foundation claim the current battlefield rehabilitation plan provides great “environmental benefits,” even as the courts find they have failed to undertake the basic impact studies required by law.

Worse than this, though, is the active, and ongoing denial of the equality of us all–by denying equal access to key parts of the battlefield experience, such as observation platforms–on the very battleground of freedom made sacred by the sacrifices of life. And limb.

Next: Observations from/on Towers and The Wound Dresser, set in stone, rest stops on the journey Toward a Cyclorama-shaped Gettysburg Memorial to The Wounded

The Eternal Sunshine Of A Spotless Battlefield

So a quick recap: the National Park Service is determined to demolish the Richard Neutra’s Cyclorama Center, built at the Gettysburg National Military Park in 1961. It was designed to house Paul Philippoteaux’s massive panoramic painting, made in 1884, depicting Pickett’s Charge, and it was sited on Cemetery Ridge, the central target of the assault and the focal point of the cyclorama. [above, a House Industries view from the narrow observation deck and ramp to the battlefield back toward the rotunda, which is largely hidden by trees.] The Cyclorama Center and a nearby Visitors Center were built as part of the Park Service’s Mission 66 program, a 10-year strategic plan to upgrade visitor and interpretive facilities and to make historic sites more car-friendly.

But that mission, and the many modernist-style buildings and structures it spawned, are viewed with disdain by the current Park Service; just as mid-century architecture is becoming eligible for historical preservation status, and as scholarship and critical appreciation is picking up, Mission 66 buildings are under threat of destruction or major alteration in line with current tastes and trends in exhibition and interpretive practice.

As it turns out, the battlefields of Gettysburg have been the site of many strategies of remembrance, commemoration, and visitor/tourist experience. More than 1,600 structures, buildings, sculptures, markers, and memorials have been erected on the site over the last 147 years, not including the railroad station, dance hall, casino, brothel, or souvenir photo studio which were on-site for the massive 50th anniversary/veterans reunion in 1913. Which means that whether officials choose to acknowledge it or not, there is a constant debate at the site about significance, appropriateness, meaning, experience, memory, and history, and that bears directly on the fate and future of the Cyclorama Center.

When I asked about the Cyclorama Center at the information desk in the sprawling, new, historicist, farm building-looking visitor center last weekend, my question was met with brusque disinterest. “It’s just a round building, nothing significant about it,” said the Friends of Gettysburg volunteer.

The Friends of Gettysburg merged with the Gettysburg Foundation in 2007. For almost two decades, the Gettysburg Foundation had helped the Park Service develop and realize the Gettysburg Battlefield Rehabilitation Project, the stated goal of which is to “rehabilitate the land to as close as possible to its 1863 appearance,” in order that the site’s “important physical qualities [will help] tell the story of the Battle of Gettysburg.”

A great deal of a 2007-8 project summary [pdf] talks about altering the terrain–removing or planting woodlands, replanting orchards, redividing fields, repairing roads and paths–which will generate vast “environmental benefits.” “The rehabilitation effort will preserve nature as it preserves history,” promises the Foundation.

But the language makes a sharp shift when discussing parts of the Cemetery Ridge Project:

…in the 43.5-acre area of Cemetery Ridge, many of those features have succumbed to natural vegetative growth and other aspects of evolution. The Cemetery Ridge project was initiated to rehabilitate this highly significant land. This project involves:

- Removal of the original Gettysburg visitor center building, which sits on the hallowed ground of Zeigler’s Grove. This older structure is being replaced by a new 139,000 square foot Museum and Visitor Center, which will open in April 2008. The new center is situated on an area that saw no major battle action, about 2/3 of a mile from the former park visitor center.

- Removal of the 1962 Cyclorama building and the parking lots and roads associated with the Cyclorama building and original visitor center building–all of which lie on soil where nearly 1,000 soldiers fell.

…

- Relocation of seven Civil War monuments to the sites where they were originally placed by veterans of the battle. These monuments were moved during the construction of the 1962 Cyclorama building and surrounding parking lots. [emphasis added]

I’m sure that the Foundation is not impugning President Eisenhower or the previous generation of Park Service officials who paved over the fallen soldiers’ hallowed ground in the first place. And I’m sure that the parking lot set to remain on the site will be only on the unhallowed parts, just like the roads that traverse the Ridge now.

And I’m sure that it wasn’t the Park Service’s fear of antagonizing the local business community that kept them from including the eventual removal of General Pickett’s Buffet, Colonel Sanders’ place, and McDonald’s [above, via jetsetmodern] from the hallowed ground across the street where several thousand other soldiers surely fell.

After all, the Park Service had no problem using eminent domain to seize and demolish the Gettysburg National Tower [left]. Built in 1974 on private land adjacent Cemetery Ridge, the controversial 307-ft tower was destroyed with great fanfare in 2000.

After all, the Park Service had no problem using eminent domain to seize and demolish the Gettysburg National Tower [left]. Built in 1974 on private land adjacent Cemetery Ridge, the controversial 307-ft tower was destroyed with great fanfare in 2000.

And then there’s the to-be-resited monuments, part of the “largest collection of outdoor sculpture in the world,” which were not, of course, present in 1863, but which were “originally placed by veterans of the battle.” Which is, of course, the second-most-irrefutable argument after “hallowed ground where soldiers fell.” [I’m sure the hundreds of additional markers placed by the War Department, and all the other non-veteran-related structures that have accreted on the site–including the incredible WWII-era, government-issue observation towers like the one along the Confederate line–will be rehabilitated away in Phase II.

Next: Some Pointers, or What To Do With Neutra’s Gettysburg Cyclorama Center?

‘The Largest Collection Of Outdoor Sculpture In The World’

The significance of the battle at Gettysburg was seized upon almost immediately, both for the vast scale of the casualties, but also because of the strategic and symbolic importance in the North of repelling the Confederate incursion. Dealing with overwhelming death, destruction, and injury immediately overwhelmed the town, and thousands of visitors streamed in to find and help family members.

Efforts to memorialize the battle and secure the battlefield also began immediately. Lincoln’s address just four months later was, after all, at the dedication of the National Solders Cemetery on a fought-over piece of land. Within weeks, historian John Bachelder began interviewing officers and attempting to pinpoint key movements and events leading up to and following the battle. And after the war, he prepared a comprehensive, if unreconciled, report of thousands of interviews and onsite surveys with survivors. Land acquisition also kicked in immediately, and a Gettysburg Battle Memorial Association was quickly formed. Because of its proximity and well-developed transportation, Gettysburg quickly became a popular tourist destination.

Memorials were placed on the battlefield to mark the sites of action engaged by individual regiments in the 1870s, but the pace picked up in the 1880s, as the 25th anniversary of the battle approached. As Wikipedia has it, survivors of the battle returned to the land to remember their individual and collective experiences, and to mark their significant events–battles, movements, victories, deaths–on the site itself:

For the Union side, virtually every regiment, battery, brigade, division, and corps has a monument, generally placed in the portion of the battlefield where that unit made the greatest contribution (as judged by the veterans themselves). Most regiments also have boundary markers placed to show their positions in defensive lines or in the starting lines for their assaults. The placements are not always definitive, due to sometimes faulty memories of the veterans or to the problems resulting from attempts to represent multiple days of battle fought on the same ground, most notably Cemetery Ridge.

When the site was transferred to the War Department, over 1,600 bronze markers were erected, based on the official history of the battle [not Bachelder’s].

The non-profit Gettysburg Foundation calls it “The largest collection of outdoor sculpture in the world.” But it’s even more than that. All these structures, sculptures, and monuments fill the landscape and connote a previous generation’s specific strategy of remembrance. And each, no matter how subjective, seemingly incidental, or retrospectively problematic, now bears the weight of that generation’s history.

Even a fence. At some point in the past, a section [reportedly a quarter of the original size] of the Copse of Trees which was Gen. Lee’s chosen focal point for the Confederate attack was rendered sacred, like a home cemetery, and fenced off from public access. The generic 19th century wrought iron fence, damaged by a fallen tree, but set for restoration, is visible behind this c.1880s War Dept. plaque for the Fifteenth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry:

The position of this regiment in line of battle

is marked by its monument

235 yards due south.

It charged up to this point and attacked Pickett’s

division in flank as his troops were coming

over the stonewall.

The battlefield sprouted other structures alongside these markers and memorials. In 1884, at the height of the Cycloramas’ popularity, the railroad laid tracks across the field of Pickett’s Charge to its new Round Top Park, an entertainment center on Little Round Top. A casino was added in 1913, the year the Boston Cyclorama came to Gettysburg in time for the Great Reunion, a conciliatory event that brought over 50,000 Civil War veterans together at Gettysburg. The veterans from all states re-enacted Pickett’s Charge, which ended with the exchange of handshakes and speeches. [It wasn’t until 1939, after the 75th anniversary, that the amusement park’s structures, and the tracks themselves, were removed.]

After WWII, Pres. Eisenhower’s development of the interstate highway system was coupled with the National Park Service’s Mission 66, a 10-year strategic plan to increase the accessibility of its sites to cars, and to provide high-quality interpretive services for its increasing throngs of visitors. Eisenhower took particular interest in Gettysburg where, while president, he decided to purchase his first home, a farm, precisely because it was built on battlefield ground. He retired to the house in 1959; it is now a presidential memorial within the expanded Military Park.

Thus is the victory of World War II, and the postwar boom, and our modern entertainment experience culture inextricably intertwined with the memorial to the bloodiest battle of the Civil War. And now we have a brief movie lesson by Morgan Freeman, and an economy where the only jobs in town that don’t involve wearing a hoop skirt are selling Civil War Orange Fudge at the Gettysburg Outlet Mall. But as the railroads and casinos and dance halls–and the Cyclorama itself–show, this spectacle- and souvenir-centered culture is not a transformation or desecration, only an upgrade in technology.

Cyclorama Center rendering, Richard Neutra, via mission66.com

But Mission 66 was too much of a good thing. The Park Service has long strained under its visitor volume; some structures were outgrown, others left to decay because of deferred maintenance. Many, like Neutra’s Cyclorama, were built in a mid-century modernist idiom, which preservationists have been slow to preserve, and which the Park Service [currently] hates. According to Mission 66 architectural historian Christine Madrid, the Park Service considers the modernist structures “a post-war mistake.” And they bridle, not only at their historical significance, but at the very notion that the Park Service is not the author and custodian of history, but just the biggest of its many actors.

Next: The Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Battlefield

On Richard Neutra’s Cyclorama Center, Or Gettysburg Memorial: The Making Of

We just got back from a weekend trip to Gettysburg, PA, and I was not quite prepared to be so fascinated by it. Gettysburg the town was attacked the Confederate Army in the Civil War partly because of its symbolic value [as a Northern target], but also because so many roads converged there. It turned out several of the meandering paths I’m interested in converged there, too.

Without knowing exactly where it was, I was interested in seeing the closed Cyclorama Center, designed in 1962 by Richard Neutra. In 2008, after relocating the Cyclorama itself–one of four extraordinary 359-ft long panoramic paintings made in the 1880s by Paul Philippoteaux [three remain]–to a new Visitors Center, the National Park Service began trying to demolish Neutra’s Cyclorama Building. Neutra’s son Dion and other preservationists are contesting this plan in court.

Well, it turns out the Cyclorama’s right on Cemetery Ridge, near the Confederate Army’s key attack on the center of the Union line. Which turns out to make sense, because that site was the focal point Philippoteaux chose for the paintings. This Cyclorama was on display in Boston for many years, until it was relocated to Gettysburg the town in 1913. The Park Service bought it, restored it, and then re-sited it to the very site it depicted, in time for the 100th anniversary of the battle.

The Park Service’s reasons against keeping the Cyclorama Building are partly logistical–it couldn’t accommodate the current number of visitors and cars; partly technological–the state of the Cyclorama art now involves multimedia light and sound elements, as well as 3D dioramas, which were apparently present in Boston, but not in subsequent installations. But its main argument is curatorial–it’s now considered inappropriate to place such interpretive structures directly on the site itself. The contemporary building thus thwarts their attempt to restore the battlefield to its pastoral, pre-1863 condition.

The first argument is undoubtedly true, but it doesn’t preclude the NPS from adapting the building to some kind of other, lower-impact use. The second argument is true, too, and I’d guess that they feel they’re getting the most out of their Cyclorama Experience now. Plus they now get to charge $10.50 for a ticket.

It’s the third argument that turned out to be so confounding and complicated, because the battlefield is literally jammed with markers and structures, not just monuments and memorials, that have been put there by successive generations as part of the remembering and memorializing process. The Cyclorama and its building are among the most important chapters in the post-war history of Gettysburg, and the Park Service’s plan to destroy the building would be highly questionable even if it hadn’t been designed by one of the country’s most well-known modernist architects.

Just about a month ago, a federal judge found that the Park Service had failed to study or consider the impact of demolishing Neutra’s building, which they had lobbied to keep off the National Register of Historic Places.

I think I’ll be breaking this up over several posts.

Next: ‘The largest collection of outdoor sculpture in the world’

‘It’s An Inducement To Memory’

Giuseppe Panza di Biumo, interviewed by Christopher Knight in 1985 for the Archives of American Art:

DR. PANZA: Well, the connection between Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art was made through Rauschenberg, because if you look at Rauschenberg, you see also the sign of the painting. We don’t see only the collage, also the object, the real object. And for this reason, it was natural for me to arrive at the Pop Art. However, when the Rauschenbergs came into my house there was some people which was very interested, but very few, but some was very fascinated by the work by Rothko and Kline, and Tapies, and to see this kind of art so different, so vulgar, made with the objects which are really found by upsetting the container of the trash, was a scandal for these people. [Laughs.] But I felt a great interest in the work by Rauschenberg because I see from the nature of this details, a relationship to something which happened in his past. It’s an inducement to memory, the work of Rauschenberg. Are all the ties made with the connection to something real, which is fading away, because it’s a fact which happened in the distant past when perhaps the artist was young. The quality of this material, which became old because are perishable materials. The paper, the wood, the objects add this kind of distance to the memory, making the object stronger because is alive in the memory. Because it’s a matter of fact, but something which we have strong experience in the distant past, is by the memory in some way changed, became more beautiful, because lose reality and get more ideal reality. This process is very strong in the work of Rauschenberg, especially in the ones made in the fifties.

Just working my way through. Panza’s English doesn’t skim very well, but his descriptions of James Turrell installations are fantastic, some of the clearest I’ve ever read. For example, this account of a 1973 visit to a room in the artist’s house, which I confess, I’ve never heard of–is it a reference to the Main and Hill Studio installations in 1968-70 mentioned in Turrell’s bio?:

DR. PANZA: In Santa Monica, in his house, there was another room which was completely dark. This room was nearby a street corner, with lights in the middle of the street. One side of the room was overlooking a small road with a little track. The other side was looking at the main street with many cars passing through. And there was a lamps of public light nearby; there was some small houses nearby. And Turrell, at the end wall of this room, made holes which was possible to open and to close in different positions of the wall. Opening the hole was facing the streetlight, it was possible to have inside the room only the light coming from the red, the green and the yellow light, leaving [off] the light of the street.

MR. KNIGHT: Of the streetlight?

DR. PANZA: Yes, the streetlight. And the room was filled of, for some minutes, of a beautiful red light. And after, the yellow one. And after, the green one.

MR. KNIGHT: And it would change.

DR. PANZA: And closing this wall but opening another one, it was possible to see only the light projections of the cars which was passing fast in the main street. And this light was coming inside the room like a lightning, filling the room with very strong light, but for a very short time. And afterward disappear; the room became again dark. Opening another hole, it was possible to see only the car coming from the small street, and for some minutes the room was completely dark, but after, some small dim light was coming into the room stronger and stronger. This light had shape, and this shape was going around the room when the car was turning in the main street. And there was a completely different feeling of the light. And opening another one, it was possible to have only the light coming from the far away public light from the street, not the one nearby the house, but one very far. And this light was very dim, but was filling, in a very peaceful way, the room. It looks like the moonlight. It was giving the same kind of emotion, because was visible only the shadow of the objects inside. There was a confused notion of the volume of the space. The room was looking very much larger, almost endless, because there was almost no shadow, a very faint shadow. Everything inside the room was looking like having lost material quality, gaining some kind of ideal entity, which was no more earthly, but heavenly. Something very strange, very metaphysical. And there was a series of this experiences which was very beautiful, made in a very simple way, showing the quality of many kind of light.

This use of only found light, it’s like those seemingly pop/superficial pieces that use reflected light from TVs showing cartoons, like in the Mondrian Hotel’s elevator lobbies, crossed with a quintessentially Los Angeles mockup of the timeless/profundity of Roden Crater. Someone please tell me this still exists.

update: haha, of course not. It turns out it’s the building that used to be called the Mendota Hotel, and the works are his seminal, site-specific, Happening-like Mendota Stoppages. I’d always read Mendota as a studio, not a house [though it was, in fact, both.] Of course it is now a Starbucks.

The Battle of Hürtgen Forest

For the Allied forces, The Battle of Hürtgen Forest was the longest and one of the bloodiest, most pointless battles of World War II. Between October 1944 through February 1945, over 33,000 US soldiers were killed in the dense fir forest filled with minefields and fortifications.

Even when the battle turned immediately hellish, far-off Allied generals kept pressing for “victory,” which at the time basically meant preserving the pride of the US Army by not retreating, even though there was no apparent strategic value to the German territory.

At least that’s Charles Whiting’s point in The Battle of Hürtgen Forest, his harrowing-to-overwrought, GI-friendly history, published in 2000. [I bought my copy on Amazon.]

As Wikipedia points out, though, Germany suffered almost as many casualties defending the forest because it stood between the US and a potentially vital dam, and it was a staging ground for the fast-approaching Ardennes Offensive/Battle of the Bulge.

Still, none of that was known or acted upon at the time by US forces, and it certainly wasn’t communicated down the line to the soldiers pinned down for days in their nearly useless foxholes.

The photos in Whiting’s book are somewhat cursory, and when I imagine the conditions, I inevitably fall back to the episode on the wintertime siege of Bastogne from HBO’s Band of Brothers. So Dmitri Kessel’s 1951 photo for LIFE, depicting the bombed out, burned out ruins of the once-impenetrable forest kind of caught me off guard.

My great uncle Lark was a staff sergeant in Hurtgen Forest. He’d already fought in Africa, Sicily and France when he was killed on October 9th, one of the earliest casualties of the battle. When it published his obituary a month later, The Richfield Reaper (UT) said only he died “somewhere in Germany.” I’m not sure if anyone in my family has ever inquired after or discussed Uncle Lark’s experience during the last months and days of his life. But I suspect it was pretty damn grim.

Hurtgen Forest, Germany, 1951, photographed by Dmitri Kessel for LIFE Magazine [life@google]

The Battle of Hürtgen Forest [wikipedia]

From The Richfield Reaper

Greg Knauss’s mention of the ancient web and an obituary spurred me to back up a little piece of my own hard drive that is the web. From Rootsweb/Ancestry.com’s republished obituaries from Piute County, UT, is by great uncle’s obituary, from the Nov. 9, 1944 issue of the Richfield Reaper:

St. Sgt. Lark Allen, 27, son of Mr. and Mrs. Chester Allen of Antimony, was reported killed in action on October 9, somewhere in Germany.

He had been wounded July 16 and released September 5 and sent back into active duty and had been overseas two years.

St. Sgt. Allen had taken part in the African invasion, the campaign in Sicily and in France. He entered the service July 7, 1941.

He has been awarded the bronze star and the purple heart was sent to his parents after he was wounded.

He was born in Circleville and attended the schools there. After graduating from the Circleville high school he attended the B.A.C. at Cedar City.

Surviving besides his parents of Antimony are the following brothers and sisters: Mrs. Dot Hall, Richfield; Miss Joye Allen, Logan; Champ Allen, Marysvale, Wayne Allen, Camp Pendelton, California and Calvert Allen, Richfield.

Memorial services will be held Sunday afternoon at 2 p.m. in the Antimony ward chapel.

(Richfield Reaper, 9 November 1944)

My dad was born just a couple of months after his uncle was killed. His parents named him Lark.

Still In Saigon

“I don’t know if you can escape what you are,” said Philip Van Cott, a retired US Marine and Vietnam War veteran who began treatment for PTSD ten years ago.

Generation B | The Damage of Vietnam, Four Decades Later [nyt]