The significance of the battle at Gettysburg was seized upon almost immediately, both for the vast scale of the casualties, but also because of the strategic and symbolic importance in the North of repelling the Confederate incursion. Dealing with overwhelming death, destruction, and injury immediately overwhelmed the town, and thousands of visitors streamed in to find and help family members.

Efforts to memorialize the battle and secure the battlefield also began immediately. Lincoln’s address just four months later was, after all, at the dedication of the National Solders Cemetery on a fought-over piece of land. Within weeks, historian John Bachelder began interviewing officers and attempting to pinpoint key movements and events leading up to and following the battle. And after the war, he prepared a comprehensive, if unreconciled, report of thousands of interviews and onsite surveys with survivors. Land acquisition also kicked in immediately, and a Gettysburg Battle Memorial Association was quickly formed. Because of its proximity and well-developed transportation, Gettysburg quickly became a popular tourist destination.

Memorials were placed on the battlefield to mark the sites of action engaged by individual regiments in the 1870s, but the pace picked up in the 1880s, as the 25th anniversary of the battle approached. As Wikipedia has it, survivors of the battle returned to the land to remember their individual and collective experiences, and to mark their significant events–battles, movements, victories, deaths–on the site itself:

For the Union side, virtually every regiment, battery, brigade, division, and corps has a monument, generally placed in the portion of the battlefield where that unit made the greatest contribution (as judged by the veterans themselves). Most regiments also have boundary markers placed to show their positions in defensive lines or in the starting lines for their assaults. The placements are not always definitive, due to sometimes faulty memories of the veterans or to the problems resulting from attempts to represent multiple days of battle fought on the same ground, most notably Cemetery Ridge.

When the site was transferred to the War Department, over 1,600 bronze markers were erected, based on the official history of the battle [not Bachelder’s].

The non-profit Gettysburg Foundation calls it “The largest collection of outdoor sculpture in the world.” But it’s even more than that. All these structures, sculptures, and monuments fill the landscape and connote a previous generation’s specific strategy of remembrance. And each, no matter how subjective, seemingly incidental, or retrospectively problematic, now bears the weight of that generation’s history.

Even a fence. At some point in the past, a section [reportedly a quarter of the original size] of the Copse of Trees which was Gen. Lee’s chosen focal point for the Confederate attack was rendered sacred, like a home cemetery, and fenced off from public access. The generic 19th century wrought iron fence, damaged by a fallen tree, but set for restoration, is visible behind this c.1880s War Dept. plaque for the Fifteenth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry:

The position of this regiment in line of battle

is marked by its monument

235 yards due south.

It charged up to this point and attacked Pickett’s

division in flank as his troops were coming

over the stonewall.

The battlefield sprouted other structures alongside these markers and memorials. In 1884, at the height of the Cycloramas’ popularity, the railroad laid tracks across the field of Pickett’s Charge to its new Round Top Park, an entertainment center on Little Round Top. A casino was added in 1913, the year the Boston Cyclorama came to Gettysburg in time for the Great Reunion, a conciliatory event that brought over 50,000 Civil War veterans together at Gettysburg. The veterans from all states re-enacted Pickett’s Charge, which ended with the exchange of handshakes and speeches. [It wasn’t until 1939, after the 75th anniversary, that the amusement park’s structures, and the tracks themselves, were removed.]

After WWII, Pres. Eisenhower’s development of the interstate highway system was coupled with the National Park Service’s Mission 66, a 10-year strategic plan to increase the accessibility of its sites to cars, and to provide high-quality interpretive services for its increasing throngs of visitors. Eisenhower took particular interest in Gettysburg where, while president, he decided to purchase his first home, a farm, precisely because it was built on battlefield ground. He retired to the house in 1959; it is now a presidential memorial within the expanded Military Park.

Thus is the victory of World War II, and the postwar boom, and our modern entertainment experience culture inextricably intertwined with the memorial to the bloodiest battle of the Civil War. And now we have a brief movie lesson by Morgan Freeman, and an economy where the only jobs in town that don’t involve wearing a hoop skirt are selling Civil War Orange Fudge at the Gettysburg Outlet Mall. But as the railroads and casinos and dance halls–and the Cyclorama itself–show, this spectacle- and souvenir-centered culture is not a transformation or desecration, only an upgrade in technology.

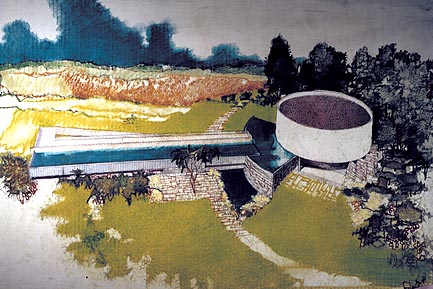

Cyclorama Center rendering, Richard Neutra, via mission66.com

But Mission 66 was too much of a good thing. The Park Service has long strained under its visitor volume; some structures were outgrown, others left to decay because of deferred maintenance. Many, like Neutra’s Cyclorama, were built in a mid-century modernist idiom, which preservationists have been slow to preserve, and which the Park Service [currently] hates. According to Mission 66 architectural historian Christine Madrid, the Park Service considers the modernist structures “a post-war mistake.” And they bridle, not only at their historical significance, but at the very notion that the Park Service is not the author and custodian of history, but just the biggest of its many actors.

Next: The Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Battlefield