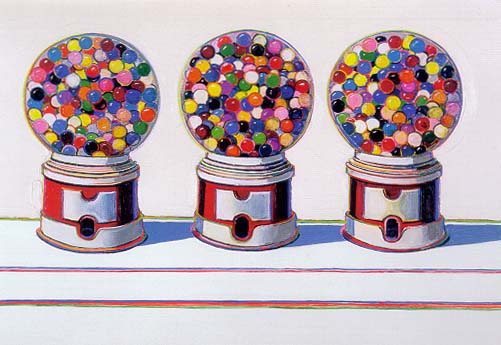

Of the three Mormon-raised artists I'll be talking about at the Sunstone Symposium on January 31st, painter Wayne Thiebaud is probably the most recognizable and accessible. Thiebaud's brightly lit paintings of cakes, pies, candy, and other American diner delights were shown along side Pop Art from the earliest days of the movement, particularly seminal Pop exhibitions in 1962 at Sidney Janis Gallery and the Walter Hopps-curated show at the Pasadena Museum, "New Paintings of Common Objects."

You kind of half-think it's a joke that Thiebaud's subject matter--desserts--would have a link to his Mormon upbringing. Surely, I'm not making a serious point that Thiebaud is painting that most culturally Mormon of all foodstuffs--refreshments. Actually, I think he makes the point himself.

Compare the language in these passages from a 2001 interview Thiebaud gave for the Smithsonian Archive of American Art. The first is about growing up and the Church:

WAYNE THIEBAUD: My grandmother had, I think, eleven children. She lived to be 99. And my father, coming from another religion - Baptist, I think, if I remember - joined the Mormon Church, and was eventually an enthusiast, or was a- It's a lay ministry, Mormonism, and he finally became a bishop. So I was a bishop's son.Thiebaud then ties his paintings to the past--his past--in a couple of relevant ways:SUSAN LARSEN: Did the-

WAYNE THIEBAUD: But the Mormon community is very, very intersupportive. And- and so it was a very nourishing environment. I was what you'd call today, I think, a spoiled child.

SUSAN LARSEN: Mm-hm. Did you have a lot of people around you and people caring about you?

WAYNE THIEBAUD: Lots of aunts and uncles, that large family, so that it was- it was a wonderful kind of way, I think, to grow up, psychologically. In terms of the intellectual tradition, Mormonism has a very strange association with that, so it's... That division occurred later on, and I'm no longer involved very much at all with it.

...

SUSAN LARSEN: In your family circle, was there much interest in culture, either music or art or pop- popular culture?

WAYNE THIEBAUD: Yes, on a kind of- a kind of very basic, almost folk level. The Mormon Church sort of encourages all kinds of performances. People get up and talk, and we were often encouraged to do, like, what they call one minute talks or three minute talks.

SUSAN LARSEN: What were they about?

WAYNE THIEBAUD: Mostly- well, mostly kind of hearty and humorous and religious or... little talks.

SUSAN LARSEN: Uh-huh, right.

WAYNE THIEBAUD: Lots of plays, dances. But very family oriented always.

SUSAN LARSEN: And so this was a- a factor in your weekly life, and things to look forward to and take part in? You took part in these?

WAYNE THIEBAUD: Yes, oh yes, very much so.

SUSAN LARSEN: Yeah, yeah. Uh-huh. It wasn't just watching, but participating.

WAYNE THIEBAUD: Yes, pretty much- pretty much centrally involved. Even if I were, for instance, to go in the - which I eventually did - become a scout, the scout troop was in the Mormon church. And if you went to a dance, it was at the Mormon statehouse [i.e., stakehouse. -ed.]- or church house. So it really was a- a community, a rather close knitted, intersupported environment.

SUSAN LARSEN:...The- the classic still life paintings that you've done often seem to feature comfort food or middle class kind of things that most people can access, that most people have access to, or have tasted or have...Joy, pleasure, comfort, nostalgia, continuing support, no troubles, these are the motivating feelings and evocations Thiebaud cites for his work.WAYNE THIEBAUD: Right, and they're available in almost every place in America. Same buffet spread in almost everywhere.

SUSAN LARSEN: Is that something that- that is important in the choosing of things to your, or was there...

WAYNE THIEBAUD: I think maybe part- certainly, part of it. But I start out with these very formalist problems. But certainly, toy counters and restaurants, which I've worked in, those experiences always, for me, have to have some footing in them, in that world that I, you know, I've lived in. And people will often ask, "Well, you never painted pizza, you never painted spaghetti." And I'll say, "Well, it's not..." Yes, now everybody has pizzas everyplace, but my things have a lot to do, I suppose with nostalgia. I think Allan Kaprow once said that they're very nostalgic paintings. They go, really, back to the thirties and forties. And the evolution of, let's say, European influence on the decoration of pastries doesn't really reach Medicine Bow, Wyoming; it's just not the same. So there is that part, I think, which is crucial. Gumball machines, gambling machines, automobiles Even American cities and the juxtaposition of strange architectural differences, all the way from gothic to modern, and that the cities sort of grow up without plans, like Paris and so on. And even American agriculture, I think, was seemingly different in terms of its mechanization. But also, it's sort of artfulness, in terms of how they make fences or design roads or...

...

SUSAN LARSEN: People seem to take enormous immediate pleasure in your paintings. (inaudible)

WAYNE THIEBAUD: Yes, that's- I think that's an inherent- can be an inherent danger, I'm supposed. But I'm delighted when people are able to smile at the work, and I- I hope it has a sense of humor and- and joyousness; that would be my- my hope.

SUSAN LARSEN: It seems because those things are in most of our common experience, I think there- there's almost a kind of endearing welcome that- that the subject matter proposes to a lot of viewers. It's- it's as though you were there when they were a kid. You remember those tastes, those things. And there's- those are moments of inexpensive pleasure that is available to most people. Very democratic, kind of. Better than showing something special and strange that only...

WAYNE THIEBAUD: It's an interesting question, isn't it, about how that comes about. I don't think it can be faked. Like people who, say, try to fake... We were talking earlier about misery or- or inhumanity to man. That's... I mean, if you're raised in an atmosphere of continuing support and no troubles, then it's very hard to make agony a real thing, or to affect primitivism or...Or in the case of even something like joyousness. If your life hasn't been joyful, I don't know how you'd ever get it into your paintings.

The references and resonances between Thiebaud's work and Edward Hopper's are commonly recognized, as are his bigger picture interest in exploring consumerism and popular culture generally. But the idyllic past in Thiebaud's memory is not just American, Western, or Californian; it's Mormon.